Establishing a Slave Society: Virginia and the 1705 Slave Codes, Part 1

About the latter end of August [1619], A Dutch man of Warr of the burden of a 160 tunnes arrived at Point-Comfort, the Comandors name Capt. Jope, his Pilott for the West Indies one Mr Marmaduke an Englishman. They mett with the Treasurer [an English vessel that routinely sailed between London and Virginia] in the West Indyes, and determyned to hold consort shipp hitherward, but in their passage lost one the other. He brought not any thing but 20. and odd Negroes, which the Governor and Cape Merchant bought for victuals (whereof he was in greate need as he pretended) at the best and easyest rates they could.

–John Rolfe to Sir Edwin Sandys, January 1619/20

With this arrival of the first Africans in the colony of Virginia, England entered the world scene of the slave trade and changed the course of American history. Prior to this, individual voyages by English ship captains—John Hawkins is credited as the first Englishman to engage in the transatlantic slave trade—did capture Africans but these slaves were sold elsewhere and was not a regular part of the economy of England. By the time Jamestown had been established in 1607, England was only twenty years removed from its first colonization attempt on the Outer Banks of North Carolina, the famed Lost Colony of Roanoke. Just like with colonizing in the New World, England lagged its rivals, the Spanish, Portuguese, and the Dutch, in the slave trade in the 17th century, but by the 18th century England would become equal to these rivals in the slave trade. This would be thanks to the Virginia economy becoming reliant on tobacco as a cash crop and the infusing of enslaved Africans into the colony, resulting in the codes Virginia passed over the 100 years from the arrival of the first Africans.

When these “20. and odd Negroes” arrived at Jamestown in 1619, there were no laws in the colony on slavery. As a matter of fact, in the same year of their arrival, the first democratic body to be established in America had been formed, the House of Burgesses. In England and other of the major European powers of the time, slavery did not exist nor laws for such. It was in the colonies of the major world players that slavery existed.

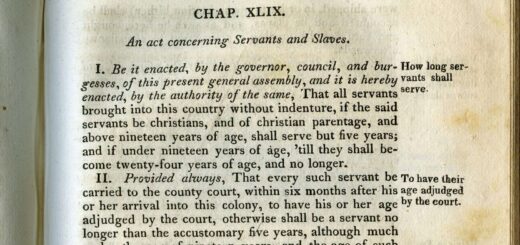

In the early part of the 17th Century, the primary form of labor in Virginia was indentured servitude. Enterprising men with capital, vision and a hunger for land brought to the colony people who sought a new start in the colony. In many cases England sent the dregs of English society. Those who could afford to, paid the passage of indentured servants to Virginia. These servants would then work for a period of four to seven years for the person who brought them over, depending on the terms of the contract. In return, the person furnishing passage for the indentured servants would receive fifty acres of land per head, hence the advent of the headright system.

Early on, indentured servitude was the primary form of labor in the colony. One of the reasons was life expectancy. In the beginning stages of the 17th century, because of deaths from wars, illness, and poor living conditions, life expectancy in Virginia was low. It was more logical and economical for plantation owners to pay passage for indentured servants to come over and serve for a number of years, usually four to seven years. It required less expenditure and allowed plantation owners to reap the maximum profits from their efforts. As the 17th century progressed forward, life expectancy began to rise and in turn, made it more feasible for plantation owners to seek a more permanent form of labor, expending more for that source, but with greater rewards. Slavery became that source of labor. The enslaved could be held in bondage for life. The enslaved cost more than paying for indentured servants, but the longer life expectancy among the elite allowed them to realize greater profits by enslaving others for life, not having to free them at the conclusion of a term of service and provide them with what amounted to a severance package (which required an output of capital or commodities from masters).

As there were no laws for the enslaved prior to 1660, Africans who were brought to the colony were sold as indentured servants and in some cases they were able to obtain freedom after serving their masters for a period of time. The status of Africans in the first half of the 17th Century in Virginia though is a point of contention considering how ambiguous the status of those Africans was. As Brent Tarter states in his book, Vignettes of Colonial Virginia, “it appears that the assumption among most white people was that Africans and descendants of Africans were enslaved for life, not indentured under a contract to work for a stated period of years.” One African who was able to obtain their freedom was Anthony Johnson. Brought to Virginia in 1621 and sold as an indentured servant, Anthony was able to obtain his freedom, along with his wife, Margaret, by around 1635. He went on to amass land and prospered as a tobacco planter on Virginia’s Eastern Shore and later in Maryland.

Since no slave laws were in place early on, Africans were treated in a similar fashion as white indentured servants. Before slave laws were passed, Africans were accorded the same opportunities for their freedom dues at the end of service. But this was not to last long.

Though there were no laws on the books defining slavery, there were a couple of judgements that were race based, one in 1630 and the other in 1640. A judicial proceeding for September 17, 1630 notes that “Hugh Davis [a white man] to be soundly whipped, before an assembly of Negroes and others for abusing himself to the dishonor of God and shame of Christians, by defiling his body in lying with a negro; which fault he is to acknowledge next Sabbath day.” Another judgement from 1640 was for a white man, Robert Sweet, “to do penance in church according to laws of England, for getting a negroe woman with child and the woman whipt.’ Despite no laws being in place for interracial relationships, there were racial prejudices at work early on in the colony, especially in regards to sexual relations between the races.

Two major events in Virginia occurred in 1640 that set the colony and future colonies, states, and events on a course towards the darkest institution established in America. At the January 6, 1639/40 session of the Virginia House of Burgesses, presided over by Governor Sir Francis Wyatt, a series of thirty-four new acts, or laws, were adopted. Act X states that “ALL persons except negroes to be provided with arms and ammunition or be fined at pleasure of the Governor and Council.” This law was a form of social control as it provided for the arming of white colonists and excluded Africans and Blacks from being able to own firearms.

The second event to occur in Virginia in 1640 was one that legally codified race-based slavery in the colony. John Punch, a Black servant, and two white indentured servants of Hugh Gwyn, ran away. They were captured in Maryland and brought back to the colony. The two white indentured servants received and additional four years of service added to their terms of indenture. John Punch’s sentence was servitude “for the time of his natural life.” Punch became the first African sentenced to slavery in Virginia, based only on the color of his skin. John Punch’s case marks a pivotal moment that separated the races between “white” and “black”, and a basis for what became chattel slavery, where those enslaved were deemed as property and a commodity, rather than human beings.

But we are not there yet. The institution of slavery was not yet legalized and codified into Virginia law, but it is important to note that forces were at work leading Virginia in that direction. Indentured Africans were still able to obtain their freedom at the conclusion of their terms of indenture. Not only that, they were also able to gain their freedom on religious grounds. Many Christian denominations did not like or support slavery and they believed it wrong to enslave others of the Christian faith. Enter Elizabeth Key.

Elizabeth Key and her case for freedom

Elizabeth Key—spelled in some documents as Kay or Kaye—was born between 1630 and 1632, likely on her father’s settlement in what is today the city of Newport News. Her father was Thomas Key, a white man and member of the Virginia House of Burgesses in 1630. He had a white wife and at least one child with that wife. Elizabeth’s mother—her name is not mentioned in any extant records—was an enslaved woman who was owned by Thomas Key. At this stage in Colonial Virginia history, there were no laws or punishments for interracial marriages or relations. The only laws observed were for fornication, adultery, and having children out of wedlock (bastard children). Thomas appears to have received a fine for having had a child with his “Negro woman” as stated in the records of Northumberland County:

Mrs. Elizabeth Newman aged 80 yeares or thereabouts sworne and examined Sayth that it was a common Fame in Virginia that Elizabeth a Molletto nowe servant to the Estate of Col. John Mottrom deceased was the Daughter of mr. Kay; and the said Kaye was brought to Blunt-point Court [Warwick County court] and there fined for getting his Negro woman with Childe which said Negroe was the Mother of the said Molletto and the said fine was for getting the Negro with Childe which Childe was the said Elizabeth…

In 1636, Thomas Key began planning on going back to England, taking his white family with him. He made an agreement with Humphrey Higginson, handing Elizabeth over to him to work for him for a period of nine years. As part of this arrangement, Higginson was to treat her well and if he were to relocate to England before the end of the nine years, he had to either bring her with him or free her from her period of labor. What happened to Elizabeth’s mother is unknown. Thomas Key died before making it to England. It is unknown when, but Elizabeth passed out of the service of Higginson into the service of John Mottrom, a prominent planter in Northumberland County. While in the service of Mottrom, Elizabeth had a child with an indentured white man named William Grimstead.

In 1655 John Mottrom died and ownership of Elizabeth passed to his estate. It was more than ten years since the agreement between Thomas Key and Humphrey Higginson, so Elizabeth made her move to secure her freedom. With the help of some white people, including her “friend”, William Grimstead, she moved forward with her case. Those who helped Elizabeth helped her in gathering the documentation of the agreements between her father, Thomas Key, and Humphrey Higginson.

The Northumberland County Court first heard the case and determined that she should be free. The administrators of Mottrom’s estate appealed the verdict to the General, or Quarter Court, which met four times a year in Jamestown. The General Court overturned the decision by the Northumberland County Court. With the help of some other white man or men, Elizabeth then appealed the General Courts decision to the General Assembly.

The General Assembly deemed that Elizabeth Key “by the Commom Law [of England] the Child of a Woman slave begott by a free-man ought to bee free.” English and Virginia law prohibited the enslavement of any Christian, whatever race they may be. The House of Burgesses determined that, as she was a Christian woman, she should be free. The Burgesses therefore recommended that the case go back to the county court. Early in the summer of 1656, the administrators of Mottrom’s estate requested the governor to order the count court to delay their decision until the General Court could yet again hear the case. Acting on the recommendation of the House of Burgesses, the Northumberland County Court acted on its own and freed Elizabeth Key on July 21, 1656.

Elizabeth, almost twenty years after the agreement her father had made with Humphrey Higginson, was finally free. The county court also ordered the Mottrom estate to pay her what indentured servants were to receive at the end of their term of service, an allowance of corn and clothing. The same day she was freed, Elizabeth and William Grimstead made known their intention of getting married. As there were no laws yet for interracial marriage, the two did marry and went on to have a second son and a daughter. Elizabeth Key’s case would help to set in motion events that would have a ripple, no, a tidal wave effect in Virginia, the colonies, and the rest of the nation for the next two centuries.

Documents in the Case of Elizabeth Key

Northumberland County Record Books, 1652-1658, fols. 66-67, 85, 1658-1660, fol. 28; Northumberland County Order Book, 1652-1665, fols. 40, 46, 49.—From the Old Dominion in the Seventeenth Century by Warren Billings, pgs. 195-199.

The Court doth order that Col. Thomas Speke one of the overseers of the Estate of Col. John Mottrom deceased shall have an Appeale to the Quarter Court next att James Citty in a Cause depending between the said overseers and Elizabeth a Moletto hee the said Col. Speke giving such caution as to Law doth belong.

Wee whose names are underwritten being impannelled upon a Jury to try a difference between Elizabeth pretended Slave to the Estate of Col. John Mottrom deceased and the overseers of the said Estate doe finde that the said Elizabeth ought to be free as by several oaths might appeare which we desire might be Recorded and that the charges of Court be paid out of the said Estate. [names of the jury omitted]

Memorandum it is Conditioned and agreed by and betwixt Thomas Key on the one part and Humphrey Higginson on the other part [word missing] that the said Thomas Key hath put unto the said Humphrey one Negro Girle by name Elizabeth for and during the [term?] of nine years after the date hereof provided that the [said?] Humphrey doe find and allow the said Elizabeth meate drinke [and?] apparel during the said tearme And allso the said Thomas Key that if the said Humphrey doe dye before the end of the said time abovespecified that then the said Girl be free from the said Humphrey Higginson and his assignes Allsoe if the said Humphrey Higginson doe goe for England with an Intention to live and remaine there that then hee shall carry [the?] said Girle with him and to pay for her passage and likewise that he put not of[f] the said Girle to any man but to keepe her himself In witness whereof I the said Humphrey Higginson. Sealed and delivered in the presence of us Robert Booth Francis Miryman. 20th January 1655 this writing was Recorded.

Mr. Nicholas Jurnew aged 31 yeares or thereabouts sworne and Examined Sayth That about 16 or 17 yeares past this deponent heard a flying report at Yorke that Elizabeth a Negro Servant to the Estate of Col. John Mottrom deceased was the Childe of Mr. Kaye but the said Mr. Kaye said that a Turke of Capt. Mathewes was Father to the Girle and further this deponent sayth not signed Nicholas Jurnew

20th January 1655 Jurat in Curia [“sworn in court”]

Anthony Lenton aged 41 yeares or thereabouts sworne and Examined Sayth that about 19 yeares past this deponent was a servant to Mr. Humphrey Higginson and at that time one Elizabeth a Molletto nowe servant to the Estate of Col. John Mottrom deceased was then a servant to the said mr. Higginson and as the Neighbours reported was bought of mr Higginson with the said servant both himself and his Wife intended a voyage for England and at the nine yeares end (as the Neighbours reported) the said Mr Higginson was bound to carry the said servant for England unto the said mr. Kaye, but before the said mr Kaye went his Voyage hee Dyed about Kecotan, and as the Neighbours reported the said mr. Higginson said that at the nine yeares end hee would carry the said Molletto for England and give her a portion and lett her shift for her selfe And it was a Common report amongst the Neighbours that the said Molletto was mr Kays Child begot by him and further this deponent sayth not the marke of Anthony Lenton

20th January 1655 Jurat in Curia

Mrs. Elizabeth Newman aged 80 yeares or thereabouts sworne and examined Sayth that it was a common Fame in Virginia that Elizabeth a Molletto nowe servant to the Estate of Col. John Mottrom deceased was the Daughter of mr. Kay; and the said Kaye was brought to Blunt-point Court [Warwick County court] and there fined for getting his Negro woman with Childe which said Negroe was the Mother of the said Molletto and the said fine was for getting the Negro with Childe which Childe was the said Elizabeth and further this deponent sayth not the marke of Elizabeth Newman

20th January 1655 Jurat in Curia

John Bayles aged 33 yeares or thereabouts sworne and Examined Sayth That at the House of Col. John Mottrom Black Besse was tearmed to be mr Kayes Bastard and John Keye calling her Black Bess mrs. Speke Checked him and said Sirra you must call her Sister for shee is your Sister and the said John Keye did call her Sister and further this deponent Sayth not the marke of John Bayles

20th January 1655 Jurat in Curia

The deposition of Alice Larrett aged 38 yeares or thereabouts Sworne and Examined Sayth that Elizabeth which is at Col. Mottroms is twenty five yeares of age or thereabouts and that I saw her mother goe to bed to her Master many times and that I heard her mother Say that shee was mr. Keyes daughter and further Sayth not the marke of Alice Larrett Sworne before mr. Nicholas Morris 19th Jan. 1655.

20th January this deposition was Recorded

Anne Clark aged 39 or thereabouts Sworne and Examined Sayth that shee this deponent was present when a Condition was made between mr. Humphrey Higginson and mr. Kaye for a servant called Besse a Molletto and this deponents Husband William Reynolds nowe deceased was a witness but whether the said Besse after the Expiration of her time from mr Higginson was to be free from mr Kaye this deponent cannot tell and mr Higginson promised to use her as well as if shee were his own Child and further this deponent Sayth not Signum Ann Clark

20th January 1655. Jurat in curia

Elizabeth Newman aged 80 yeares or thereabouts Sworne and Examined Sayth that shee this deponent brought Elizabeth a Molletto, Servant to the Estate of Col. John Mottrom deceased to bed of two Children and shee layd them both to William Grinsted and further this Deponent Sayth not Elizabeth Newman her marke

20th January 1655 Jurat in Curia

A Report of a Comittee from an Assembly

Concerning the freedome of Elizabeth Key

It appeareth to us that shee is the daughter of Thomas Key by several Evidences and by a fine imposed upon the said Thomas for getting her mother with Child of the said Thomas That she hath bin by verdict of a jury impannelled 20th January 1655 in the County of Northumberland found to be free by several oaths which the Jury desired might be Recorded That by the Comon Law the Child of a Woman slave begot by a freeman ought to bee free That shee hath bin long since Christened Col. Higginson being her God father and that by report shee is able to give a very good account of her fayth That Thomas Key sould her onely for nine yearesto Col. Higginson with several conditions to used her more Respectfully then a Comon servant or slave That in case Col. Higginson had gone for England within nine yeares hee Was bound to carry her with him and pay her passage and not to dispose of her to any other. For theise Reasons wee conceive the said Elizabeth ought to bee free and that her last Master should give her Corne and Cloathes and give her satisfaction for the time shee hath served longer then Shee ought to have done. But forasmuch as noe man appeared against the said Elizabeths petition wee thinke not fitt a determinative judgement should passe but that the County or Quarter Court where it shall be next tried to take notice of this to be the sence of the Burgesses of this present Assembly and that unless [original torn] shall appear to be executed and reasons [original torn] opposite part Judgement by the said Court be given [accordingly?]

Charles Norwood Clerk Assembly

James Gaylord hath deposed that this is a true coppy

James Gaylord

21th July 1656 Jurat in Curia

21th July 1656 This writeing was recorded

Att a Grand Assembly held at James Citty 20th of March 1655 Ordered that the whole business of Elizabeth Key [and?] the report of the Comittee thereupon be returned [to the?] County Court where the said Elizabeth Key liveth

This is a true copy from the book of Records of the

Order granted the last Assembly

Teste Robert Booth

21th July 1656 This Order of Assembly was Recorded

Upon the petition of George Colclough one of the overseers of Col. Mottrom his Estate that the cause concerning a Negro wench named Black Besse should be heard before the Governor and Councell Whereof in regard of the Order of the late Assembly referring the said caise to the Governor and Councell at least upon Appeale made to them These are therefore in his Highness the Lord Protector his name to will and require the Commissioners of the County of Northumberland to Surcease from any further proceedings on the said Cause and to give notice to the parties interested therein to appear before the Governor at the next Quarter Court on the fourth day for a determination thereof. Given under my hand this 7th of June 1656. Edward Digges 21th 1656 This Writeing was Recorded.

Whereas mr. George Colclough an mr. William Presly overseers of the Estate of Colonell John Mottrom deceased were Summoned to theis Court at the suite of Elizabeth Kaye both Plaintiffe and Defendant being present and noe cause of action at present appearing The Court doth therefore order that the said Elizabeth Kaye shall be non-suited and that William Grinsted Atturney of the said Elizabeth shall by the tenth of November next pay fifty pounds of tobacco to the said overseers for an non-suite with Court charges else Execution. Whereas the whole business concerning Elizabeth Key by Order of Assembly was Referred to this County Court. According to the Report of a Comittee at an Assembly held at the same time which upon the Records of this County appears, It is the judgment of this Court that the Said Elizabeth Key ought to be free and forthwith to have Corne Clothes and Satisfaction according to the said Report of the Comittee. Mr. William Thomas dissents from this judgment.

These are to Certifie whom it may concerne that William Greensted and Elizabeth Key intends to be joyned in the Holy Estate of Matrimony. If anyone can shew any Lawfull cause why they may not be joyned together lett them Speake or ever after hold their tongues Signum William Greensted Signum Elizabeth Key

21th July 1656 this Certificate was Published

in open Court and is Recorded

I Capt. Richard Wright administrator of the Estate of Col. John Mottrom deceased doe assigne and transfer unto William Greensted a maid servant formerly belonging unto the Estate of the said Col. Mottrom commonly called Elizabeth Key being nowe Wife unto the said Greensted and doe warrant the said Elizabeth and doe bind my Selfe to save here [her] and the said Greensted from any molestation or trouble that shall or futurely arise from or by any person or persons that shall pretend or claime any title or interest to any manor of service [original torn] from the said Elizabeth witness [my ha]nd this 21th of July 1659

Test William Th[omas] Richard Wright

James Aust[en]

Establishing a Slave Society

Not long after the conclusion of the Elizabeth Key case, a major shift was afoot in Colonial Virginia. In 1640, a law had been passed restricting firearm ownership to whites only. Elizabeth Key’s case was complicated for a number of reasons. There were no laws to determine who or who was not to be enslaved in Virginia. English Common Law determined that if an enslaved woman had a child with a free man, then the child should be free as well. English and Virginia law also stated that no Christian, whether white or Black should be enslaved. Elizabeth Key fell into both of these cases. She also, at the conclusion of her bid for freedom, married William Grimstead. At that point in Virginia, there were no laws forbidding interracial marriage. Elizabeth’s case can be seen as a starting point in a shift in how Africans and Blacks place in Colonial society was viewed and determined.

The first law to be passed in regards to African and Black enslaved and indentured persons came in March 1660/61. At this session of the General Assembly in Jamestown, the House of Burgesses passed a number of acts, or laws. Act XXII punished white English servants for running away with “negroes.” The act states, “That in case any English servant shall run away in company with any negroes who are incapable of makeing satisfaction by addition of time, Bee itt enacted that the English so running away in company with them shall serve for the time of the said negroes absence as they are to do for their owne by a former act.” Though the act did not punish enslaved or indentured Africans or Blacks, there is still the racial undertone. But the next law to be passed by the General Assembly at Jamestown was a monumental law that began an avalanche of successive laws that would culminate in the 1705 Virginia Slave Codes.

At the General Assembly of December 1662, the following act was passed:

Act XII.

Negro womens children to serve according to the condition of the mother.

WHEREAS some doubts have arrisen whether children got by any Englishman upon a negro woman should be slave or ffree, Be it therefore enacted and declared by this present grand assembly, that all children borne in this country shalbe held bond or free only according to the condition of the mother, And that if any Christian shall committ ffornication with a negro man or woman, hee or shee soe offending shall pay double the ffines imposed by the former act.

This single act would change the course of Virginia and United States history, forever. It is from this point that Virginia transitioned from a society with slaves, to a slave society. Thus chattel slavery was born, where those enslaved were no longer considered human beings, but as personal property that could be bought, sold, traded, or inherited like livestock or furniture. With this act, slavery was racialized and codified into Virginia law, and those enslaved had no legal rights. A clear delineation was now established between who was to be free and who was to be enslaved, with distinction drawn between the races.

With this act clear connections can be seen to the case of Elizabeth Key. She was the daughter of an enslaved woman, yet gained her freedom based on her father having been a white man and based on English Common Law. Going forward, an enslaved person would no longer be able to obtain their freedom if their mother was an enslaved person with a free white father. With this new law, sexual intercourse between races could now be punished with double the fines from a previous act.

Another act that is clearly connected to Elizabeth Key’s case came from the September 1667 General Assembly.

Act III

An act declaring that baptisme of slaves doth not exempt them from bondage.

WHEREAS some doubts have risen whether children that are slaves by birth, and by the charity and piety of their owners made pertakers of the blessed sacrament of baptisme, should by vertue of their baptisme be made ffree; It is enacted and declared by this grand assembly, and the authority thereof, that the conferring of baptisme doth not alter the condition of the person as to his bondage or ffreedome; that diverse masters, ffreed from this doubt, may more carefully endeavour the propagation of christianity by permitting children, though slaves, or those of greater growth if capable to be admitted to that sacrament.

With this act, enslaved persons could no longer use Christianity, or the conversion to it, to obtain their freedom. This further cemented the institution of slavery in the colony, eliminating yet another path of freedom. Both this act and the 1662 act that set the condition of enslavement or freedom on the status of the mother presented a problem. English Common Law, as other Christian societies stated that Christians could not enslave other Christians and the general belief was that conversion to the Christian faith could lead to freedom.

So how was it that Virginia was able to override English Common Law? England allowed Virginia to set aside certain principles of English Common Law in instances of economic interest and salutary neglect. The economy of Virginia, which relied primarily on the production of their cash crop tobacco, required a permanent and controllable labor force. Laws of Virginia such as this one were designed to eliminate legal ambiguities that might have freed enslaved people, therefore securing the investment in human property. With securing enslavers property rights of their human chattel, England encouraged the large-scale investment necessary for the plantation economy. The wealth that came from plantation culture in Colonial Virginia directly benefited the English Crown and merchants who took Virginia tobacco to market. In salutary neglect, England mostly left colonial assemblies to their own devices in governing their own affairs as a means of maintaining social order and economic productivity. England took a hands-off approach by not intervening, despite the contradiction of English Common Law, allowing Virginia’s General Assembly to create laws that defined chattel slavery.

Despite these two preceding laws, enslaved people were still able to obtain their freedom by purchasing their freedom and those of other family members. One instance of this is the case of John and Isabell Daule, an enslaved married couple who were owned by Arthur Jordan of Surry County, Virginia. The deed in which they were freed by Arthur Jordan on March 10, 1670 is recorded in the Surry County Deeds and Wills, 1657-1672, page 349 and reads:

Whereas John Daule and Isabell his wife are the Negro Sarvants of Mr. Arthur Jordan, and have this present day agreed for a vallueable Consideration to the end they might be acquitted of Such Service as they owe Me, and May Now enter upon the Makeinge of a Crop for their owne use be itt Knowne therefore to all men by these presents that I the said Arthur Jordan doe hereby release acquit and discharge the said John and Isabell from all Service dues and demands what soe ever which I the said Arthur Jordan my Executors or Administrators shall or may or ought to have or claime of them or either of them from the beginning of the world to the date here of witness my hand and seale the tenth day of March Anno Domini 1669 [1670]

Arthur Jordan Seale red wax

Sealed and delivered in presence of George Jordan George Proctor William S[h]erwood

Acknowledged in Courte by the Subscriber Arthur Jordan 3d May and recorded 13th 1670.

The next slave law to be passed, called the “Casual Killing Act”, is one of the most vile and heinous laws to be passed by Virginia’s House of Burgesses. The law passed in October 1669 states:

Act I

An act about the casuall killing of slaves

WHEREAS the only law in force for the punishment of refractory servants (a) resisting their master, mistris or overseer cannot be inflicted upon negroes, nor the obstinacy of many of them by other then violent meanes supprest, Be it enacted and declared by this grand assembly, if any slave resist his master (or other by his masters order correcting him) and by the extremity of the correction should chance to die, that his death shall not be accompted ffelony, but the master (or that other person appointed by the master to punish him) be acquit from molestation, since it cannot be presumed that prepensed malice (which alone makes murther ffelony) should induce any man to destroy his owne estate.

This act is one of the harshest ones to be passed in Virginia history. The act more or less gave enslavers a free pass to mete out punishment, unrestrained and in whatever form they saw fit, on their enslaved individuals without reprisal. There was no one that could speak up on behalf of the enslaved who were killed, as they had no legal standing in the colonial court system. Enslaved people could be punished for the simplest of infractions by masters or overseers, some of whom could be known for being extremely cruel in their treatment of the enslaved. Who knows how many fell victim to this legalized killing and murder.

Despite this law, there were a few instances in which a master killed his enslaved individual in the act of punishment and faced consequences for said actions. In 1775, William Pitman of Williamsburg went to trial for killing an enslaved boy that he owned. Unfortunately, the records do not record the name of the young boy. One night Pitman, after having gotten drunk, found the boy asleep in a stable with a horse blanket wrapped around him. Pitman tied up the boy and beat and stomped him to death. The boy’s infraction: he forgot to brush Pitman’s horse. Pitman was subsequently arrested and put on trial for murder. The case is interesting though. Enslaved people could not testify in court cases against white people. Pitman was convicted of the murder based on the testimony provided by his own son and daughter. He was hung for the murder of his enslaved boy on May 12, 1775.

Purdie’s Virginia Gazette, April 21, 1775, pg. 4, column 2, showing the court case against William Pitman. Courtesy John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library, Williamsburg, VA.

Pinckney’s Virginia Gazette, May 11, 1775, pg. 3, column 3, announcing the execution of William Pitman. Courtesy John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library, Williamsburg, VA.

From an early stage in Colonial Virginia, slave insurrections were a real fear among the white colonists. In Gloucester County in September 1663, a plot—this plot would come to be known as the Servant’s Plot—by indentured servants was uncovered and foiled when an enslaved man, John Birkenhead, exposed the plot. Birkenhead was freed by his owner, John Smith, and awarded five thousand pounds of tobacco by the House of Burgesses for having informed on the conspirators in the plot. In 1676, Bacon’s Rebellion rocked the colony. This armed rebellion was complex in all of its aspects. But one major aspect of the followers of Bacon was their station in life. Not only did Nathaniel Bacon have some prominent men who joined his ranks, but also the lower class of men including indentured servants and the enslaved. These two events helped to stoke the fears of Virginia’s white planter class and would lead to a series of laws that would tighten the grip of slavery in the colony and limit the movement and what few liberties the enslaved did have.

The rumored and foiled plots led to laws such as An Act for preventing Negroes Insurrections, passed in June 1680. The law reads:

WHEREAS the frequent meeting of considerable numbers of negroe slaves under pretence of feasts and burialls is judged of dangerous consequence; for prevention whereof for the future, Bee it enacted by the kings most excellent majestie by and with the consent of the generall assembly, and it is hereby enacted by the authority aforesaid, that from and after the publication of this law, it shall not be lawfull for any negroe or other slave to carry or arme himselfe with any club, staffe, gunn, sword or any other weapon of defence or offence, nor to goe or depart from of his masters ground without a certificate from his master, mistris or overseer, and such permission not to be granted but upon perticuler and necessary occasions; and every negroe or slave soe offending not having a certificate as aforesaid shalbe sent to the next constable, who is hereby enjoyned and required to givid negroe twenty lases on his bare back well layd on, and soe sent home to his said master, mistris or overseer. And it is further enacted by the authority aforesaid that if any negroe or other slave shall presume to lift up his hand in opposition against any christian, shall for every such offence, upon due proofe made thereof by the oath of the party before a magistrate, have and receive thirty lashes on his bare back well laid on. And it is hereby further enacted by the authority aforesaid that if any negroe or other slave shall absent himself from his masters service and lye hid and lurking in obscure places, committing injuries to the inhabitants, and shall resist any person or persons that shalby any lawfull authority be imployed to apprehend and take the said negroe, that then in case of such resistance, it shalbe lawfull for such person or persons to kill the said negroe or slave soe lying out and resisting, and that this law be once every six months published at the respective county courts and parish churches within this colony.

In the first part of this act, an addition to the 1640 law that forbade the arming of slaves with firearms, further restricted the enslaved from having any instrument that could be considered a weapon with the exception of tools used by them as part of their daily duties. Enslaved people also could no longer leave the plantations they “belonged” to without a certificate from their owners or overseers—this was the first law to restrict movement among the enslaved class. This helped to prevent the enslaved from meeting in large groups and possibly plan uprisings. They could no longer go to other plantations to visit friends or loved ones without permission of their owners or overseers. The second part of this act forbade the enslaved from striking any white person, even if in self-defense. In the first two parts of the act, the penalty for committing these offences would be getting whipped. The final part of the act deemed it unlawful for the enslaved to leave the service of their enslavers, go into hiding, and for them to resist efforts at apprehension. If an enslaved person were to resist, they could be killed at the discretion of those who captured them.

In November 1682, the General Assembly passed another act to bolster the 1680 act, further restricting the movements of the enslaved. This act reads as follows:

Act III.

An additionall act for the better preventing insurrections by Negroes.

WHEREAS a certaine act of assembly held at James Citty the 8th day of June, in the yeare of our Lord 1680, intituled, an act preventing negroes insurrections hath not had its intended effect for want of due notice thereof being taken; It is enacted by the governor, councell and burgesses of this generall assembly, and by the authority thereof, that for the better putting the said act in due execution, the church wardens of each parish in this country at the charge of the parish by the first day of January next provide true coppies of this present and the aforesaid act, and make or cause entry thereof to be made in the register book of the said parish, and that the minister or reader of each parish shall twice every yeare vizt. some one Sunday or Lords day in each of the months of September and March in each parish church or chappell of ease in each parish in the time of divine service, after the reading of the second lesson, read and publish both this present and the aforerecited act under paine such churchwarden minister or reader makeing default, to forfeite each of them six hundred pounds of tobacco, one halfe to the informer and the other halfe to the use of the poore of the said parish. And for the further better preventing such insurrections by negroes or slaves, Bee in likewise enacted by the authority aforesaid, that noe master or overseer knowingly permit or suffer, without the leave or license of his or their master or overseer, any negroe or slave not properly belonging to him or them, the remaine or be upon his or their plantation above the space of four hours at any one time, contrary to the intent of the aforerecited act upon paine to forfeite, being thereof lawfully convicted, before some one justice of peace withing the county where the fact shall be comitted, by the oath of two witnesses at the least, the summe of two hundred pounds of tobacco in cask for each time soe offending to him or them that will sue for the same, for which the said justice is hereby impowered to award judgment and execution.

Their movements restricted by the previous act, the enslaved were now further restricted in their movements by not being allowed to remain on a plantation not owned by their enslavers for more than four hours at a time. In addition, failure to comply with this law on the part of a white plantation owner could result in a fine of two hundred pounds of tobacco. These two laws were also now required to be read in church twice a year, the failure of which could result in a fine on the parish.

The final law passed prior to the 1705 Slave Codes of Virginia was an act titled “An act for suppressing outlying Slaves” and part of this act would remain in place until the mid-20th century. The law, passed in April 1691, reads as follows:

WHEREAS many times negroes, mulattoes, and other slaves unlawfully absent themselves from their masters and mistresses service, and lie hid and lurk in obscure places killing hoggs and committing other injuries to the inhabitants of this dominion, for remedy whereof for the future, Be it enacted by their majesties lieutenant governor, councell and burgesses of this present generall assembly, and the authoritie thereof, and it is hereby enacted, that in all such cases upon intelligence of any such negroes, mulattoes, or other slaves lying out, two of their majesties justices of the peace of that county, whereof one to be of the quorum, where such negroes, mulattoes or other slave shall be, shall be impowered and commanded, and are hereby impowered and commanded to issue out their warrants directed to the sherrife of the same county to apprehend such negroes, mulattoes, and other slaves, which said sherriffe is hereby likewise required upon all such occasions to raise such and soe many forces from time to time as he shall think convenient and necessary for the effectual apprehending such negroes, mulattoes and other slaves, and in case any negroes, mulattoes or other slave or slaves lying out as aforesaid shall resist, runaway, or refuse to deliver and surrender him or themselves to any person or persons that shall be by lawfull authority employed to apprehend and take such negroes, mulattoes or other slaves that in such cases it shall and may be lawfull for such person and persons to kill and destroy such negroes, mulattoes, and other slave or slaves by gunn or any otherwaise whatsoever.

Provided that where any negroe or mulattoe slave or slaves shall be killed in pursuance of this act, the owner or owners of such negro or mulatto slave shall be paid for such negro or mulatto slave four thousand pounds of tobacco by the publique. And for prevention of that abominable mixture and spurious issue which hereafter may increase in this dominion, as well by negroes, mulattoes, and Indians intermarrying with English, or other white women, as by their unlawfull accompanying with one another, Be it enacted by the authoritie aforesaid, and it is hereby enacted, that for the time to come, whatsoever English or other white man or woman being free shall intermarry with a negroe, mulatto, or Indian man or woman bond or free shall within three months after such marriage be banished and removed from the dominion forever, and that the justices of each respective countie within this dominion make it their perticular care, that this act be put in effectuall execution. And be it further enacted by the authoritie aforesaid, and it is hereby enacted, That if any English woman being free shall have a bastard child by any negro or mulatto, she pay the sume of fifteen pounds sterling, within one moneth after such bastard child shall be born, to the Church wardens of the parish where she shall be delivered of such child, and in default of such payment she shall be taken into the possession of the said Church wardens and disposed of for five yeares, and the said fine of fifteen pounds, or whatever the woman shall be disposed of for, shall be paid, one third part to their majesties for and towards the support of the government and the contingent charges thereof, and one third part to the use of the parish where the offence is committed, and the other third part to the informer, and that such bastard child be bound out as a servant by the said Church wardens untill he or she shall attaine the age of thirty yeares, and in case such English woman that shall have such bastard child be a servant, she shall be sold by the said church wardens, (after her time is expired that the ought by law to serve her master) for five yeares, and the money she shall be sold for divided as is before appointed, and the child to serve as aforesaid.

And forasmuch as great inconveniences may happen to this country by the setting of negroes and mulattoes free, by their either entertaining negro slaves from their masters service, or receiveing stolen goods, or being grown old bringing a charge upon the country; for prevention thereof, Be it enacted by the authority aforesaid, and it is hereby enacted, That no negro or mulatto be after the end of this present session of assembly set free by any person or persons whatsoever, unless such person or persons, their heires, executors or administrators pay for the transportation of such negro or negroes out of the countrey within six moneths after such setting them free, upon penalty of paying of tenn pounds sterling to the Church wardens of the parish where sich person shall dwell with, which money, or so much thereof as shall be necessary, the said Church wardens are to cause the said negro or mulatto to be transported out of the countrey, and the remainder of the said money to imploy to the use of the poor of the parish.

The first part of this act restates the 1682 Act on apprehension of enslaved peoples and having authority to kill them if they resist. A new addition to this act is that if an enslaved person is killed while being apprehended, then the owner of said enslaved person is to be reimbursed four thousand pounds of tobacco for loss of property—yes, you read that correctly, property as the enslaved were now viewed as property and not human beings.

The next part of the 1691 Act made it illegal for any English man or woman to intermarry with any Black or Indian man or woman, whether indentured, enslaved, or free. If an interracial marriage occurs, the married couple is to be sent out of the colony within three months of said union. As the House of Burgesses continues to pass these laws, you may notice that the language contained in them becomes increasingly horrible towards non-whites. For example, when describing intermarriage, the act refers to the subject as “that abominable mixture and spurious issue”, as if it grotesque or twisted. Language such as this is what helped to cause racial biases and racism to grow and fester for the future and still exists today. This law would remain on the books for the next 267 years! In the 1967 Loving v. Virginia civil rights case, the United States Supreme Court decision ruled that laws banning interracial marriage across the country violated the Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses of the 14th Amendment of the United States Constitution.

The next stipulation to the act regards children born out of wedlock, or bastard children. The law states that if a free white woman has a bastard child with any Black man, she is to be fined fifteen pounds sterling and if payment is unable to be made, then she taken into custody by church wardens and is to be bound out for five years of indentured service. The child from such relationship would be bound to service until their thirtieth birthday. If the woman happened to be an indentured servant, the church wardens were to sell her service, at the conclusion of her current service, for another five years.

In the final part of the 1691 Act, enslaved people cannot be freed by their owners unless the owner pays for the passage of said enslaved person out of the colony within six months of being freed. If the enslaver(s) do not comply with this law, they could be fined ten pounds sterling which would go to the church wardens of the parish of the locality who would then use the funds to have the freed enslaved person sent out of the colony. This part of the law became commonplace in other colonies as they did not want those who were still enslaved to make attempts at freeing themselves, seeing former enslaved people living among them.

With these preceding laws, Virginia was transformed from a society with slaves to a slave society. The laws created a legal definition of perpetual bondage, restricted movements, abilities to gather, ownership of weapons, and allowed for the meting out of harsh punishments up to and including death, without restriction. With each succeeding law, the language contained in them became more racially charged, helping to widen the racial divide in the colony. These laws also set the stage for a more comprehensive set of laws at the dawn of the next century, laws that would serve as a blueprint for other colonies to follow and adopt themselves.

References

Affidavit, 1693. Virginia Museum of History and Culture, accessed 22 October 2025. https://virginiahistory.org/learn/affidavit-1693.

Billings, Warren M. The Old Dominion in the Seventeenth Century: A Documentary History of Virginia 1606-1700. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Hening, William Waller. The Statutes at Large; Being A Collection Of All The Laws of Virginia, From The First Session Of The Legislature, In The Year 1619. Volume 1. University Press of Virginia, 1969. First published in 1823 by R. & W. & G. Bartow.

Hening, William Waller. The Statutes at Large; Being A Collection Of All The Laws of Virginia, From the First Session Of The Legislature, In The Year 1619. Volume 2. University Press of Virginia, 1969. First published in 1823 by R. & W. & G. Bartow.

Hening, William Waller. The Statutes at Large; Being A Collection Of All The Laws of Virginia, From The First Session Of The Legislature, In The Year 1619. Volume 3. University Press of Virginia, 1969. First published in 1823 by R. & W. & G. Bartow.

Another great article. I think when we look at the subject of slaves we don’t focus on the individuals. Each one has a story of courage and perseverance. Thank you for bringing the lives of these individuals to light.

Thanks Michael. As I wrote this article, my focus and scope shifted more towards something more comprehensive. At first I was going to just write on the 1705 Slave Codes, but as I researched them, I saw all these enslaved people and cases that tied directly to certain laws that were passed, and I was like, “I should somehow tie these people and their cases into the codes that were passed.” And I feel it made my article even more necessary and relevant to the subject. Thanks for checking it out my friend and colleague!!!

Interesting article on a topic rarely tacaled.

Brent, yes it’s only been in the past year or two that I have seen much on the 1705 Slave Codes. The Virginia Museum of History and Culture makes mention of it in their exhibit, Un/Bound that they have going now. There is an online article on them on Encylopedia Virginia, but it is just the text of them, no commentary or connections to cases that helped prompt certain laws like I did with my article. Glad you liked the article.