Separated by an Institution, Reunited in the Aftermath: Carter Temple Sr. and Jr. and an Unlikely Modern Connection

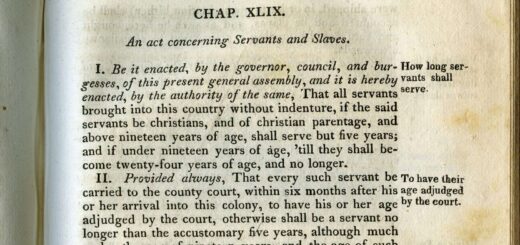

In May 2022, I wrote an article on my 6th great grandfather, Benjamin Temple of King William County, Virginia. He was a veteran of the French and Indian War, having served with George Washington and, later, was a lieutenant-colonel in the 1st and 4th Continental Light Dragoons during the Revolutionary War. Post war, Benjamin Temple served on Virginia’s Ratifying Convention to the Constitutional Convention, serving King William County alongside Holt Richeson. He and Richeson voted against ratifying the United States Constitution in a narrow vote that saw Virginia ratify in favor by a vote of 89-79. Temple also served as a Virginia State Senator under a Federalist ticket. Yes, despite voting against the Constitution, he eventually warmed up to becoming a Federalist himself.

In addition to all of what I discovered about Benjamin Temple, I also discovered that he, as a prominent Virginia man, was an enslaver. It is unknown how many people he enslaved, but recently I made a discovery of at least one enslaved person he owned, a man named either Christopher or Charles Plummity. Christopher or Charles self-emancipated from Temple’s Presquile Plantation in King William County in 1779, eventually making his way to the British in New York before they evacuated the city in 1783 at the end of the Revolutionary War. The Book of Negroes, a ledger listing approximately 3,000 Black Loyalists who escaped with the British in 1783 details this formerly enslaved man’s details. At the time of Christopher (or Charles’) departure from New York in July 1783, he was about 22 years of age, making his probable birth year 1761.

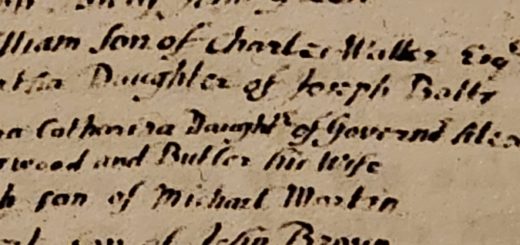

Detail from the Book of Negroes showing Charles/Christopher Plummity, bottom row.

Detail showing who Charles/Christopher being enslaved to Benjamin Temple and the location of where he was enslaved.

When I finished writing the article on Benjamin Temple and posted it, I had a feeling deep inside of me that someone would find and read my article, someone who would have a unique connection to me. But it was not the usual connection I felt that it would be. I thought to myself, that someone would reach out to me, someone whose ancestors were enslaved by either Benjamin Temple or one of his children. Prior to writing this article on him, I had been preparing myself for this to one day happen. What would I say to this person? How would our interaction go? Would that person have bad feelings towards me for what my ancestors had done to theirs? I had prepared for all possibilities.

I was not long in waiting for this unique connection that I had a feeling was coming. On November 15, 2022, it happened. A woman named Cecelia Boler had posted a comment on my article on Benjamin Temple. Her comment read:

Thank you so much for doing the research on Benjamin Temple. His son, Benjamin Burnley Temple was the enslaver of my great-great grandfather. I have always wanted to read the Wills of both men so that I could possible see my gg-grandfather’s journey. I recognized the names throughout this article and have been very interested over the years. If you think you may have seen any enslaved people’s names in your research, please let me know. Thanks again for this article.

I was stunned. I knew this was going to happen. I was excited and nervous. I asked myself, “how should I respond?” I took a deep breath and said “here we go, just be honest and speak from the heart”. Below is my first response to Cecelia (I did not know of the use of the term enslaved vs. slave at this time):

Hi Cecelia!!! Glad you enjoyed the article. Um, I honestly don’t know how to go about this, as you are the first descendant of a slave owned by someone in my family to connect with me. I’d love to know more about what you know of your 2nd great grandfather, maybe I or we could do a piggy back article, kind of a branch off of this article. Unfortunately, I have yet to find much info on the slaves that were owned by them. Unfortunately, King William County courthouse burned just after the Civil War, such a shame, many lost documents and information that could tell so much more.

Like I said though, I honestly don’t know how to go forward, as this is a first for me. Slavery was, and is, such a dark stain on our country’s history, but still one whose story needs to be told. I’m sorry for anything bad that happened to your ancestors as a result of my family. One thing I have done though over the years in my study of Virginia history, is read a lot of material on slavery to better understand the real history of what happened. Several years ago I took an Ancestry DNA test and found that I in fact have African Ancestry. I keep hoping that it happened out of love, but knowing the history of slavery, the things slave owners did to slave women, it’s likely that my slave ancestor didn’t have an option in regards to her relationship with her master. But I do celebrate having African Ancestry and an ancestor who was a slave because it is part of who I am. I Unfortunately have yet to find the ancestor who was a slave, but hope to one day, so I can learn whatever I can find about her. She would have likely come from Mali as that is where my Ancestry links me to. Anyways, I would definitely like to connect with you. Where do you live? I live in Glen Allen, Virginia. I hope to hear back from you.

Todd Long

Shortly after exchanging several emails, Cecelia and I scheduled a phone call with each other. In that phone call, one of the first things I told her was, “I’m sorry for what my ancestors did to your ancestors.” All she wanted was acknowledgement of what happened in the past, understanding, and connection. We discussed many other things. And what struck me most of our phone conversation, was that we were talking with each other like we were old friends. There was never any awkward moments. Today we keep in touch regularly. I think of her as family. Even though we are not connected by blood, that we know of, we are nonetheless connected. That connection is not in the best of ways to be connected and we are cognizant of that. But we are connected, our families are forever linked by one of the most dark and deplorable institutions in the nation’s history. Despite this, we are and have been making the best of it. Much love to you, Cecelia, and your family. Now, on to the history of our connection.

Carter Temple, Sr. and Benjamin Burnley Temple

Carter Temple Sr., according to the 1880 United States Federal Census, was born in Virginia in 1811. The location in Virginia where he was born and who his family was is unknown. He was enslaved by Benjamin Burnley Temple, son of Colonel Benjamin Temple of King William County, Virginia. Benjamin Burnley Temple married his wife, Eleanor Ettinger Clark in 1801 in Virginia. By about 1802, they had moved to Logan County, Kentucky. How Carter Temple Sr. came to be enslaved by the Temple family is unknown. He may have been enslaved to the Temple family in Virginia before being sent to Kentucky. More research is needed on the early origins of Carter, Sr., if any information on this can be gleaned at all. In 1885, the King William County Clerk’s Office burned, taking about 95% of the county’s records, so being able to trace the early origins of Carter, Sr. would prove difficult if he was born in King William County, the family seat of the Temple’s.

The earliest documentation of Carter is in the July 1838 estate inventory of Benjamin Burnley Temple, who died in 1838. In the estate inventory recorded in the courthouse of Logan County, Kentucky, Carter is listed among the enslaved of Benjamin Temple deceased, at a value of $700. Carter Temple Jr., son of Carter Sr., has on his death certificate Sarah Hayden listed as his mother. A couple of other children of Carter Sr., Frank and Lucy, are also known to have been children of this Sarah. Slave marriages were not recognized legally, but sometimes enslavers would recognize the marriages of their enslaved people. It is not known for certain if Carter Sr. was ever married to Sarah. The only known marriage he had was to a woman named Amanda. Sarah Hayden was believed to have been enslaved by a man named William Hayden. William Hayden at some point separated from his wife, Pamelia. In the settlement they had, he gave her and her daughter, Margaret, Sarah and Sarah’s children. Margaret Hayden would eventually marry a man named John Hopkins, this is how Carter Temple Jr. would likely have had the name Carr Hopkins early on in life when he was enslaved.

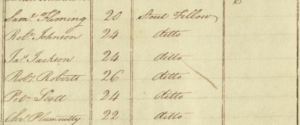

Detail of the 1838 estate inventory of Benjamin Burnley Temple, listing the enslaved including Carter Temple Sr., image courtesy of familysearch.org.

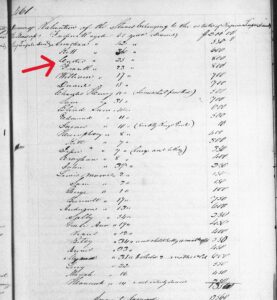

At the October 1838 session of the Logan County Court is a document listing the division of the enslaved people from Benjamin Burnley Temple’s estate. The first part of this document lists the names, ages, and valuations of the enslaved to be divided up amongst the children of Benjamin Temple. Carter Temple Sr. is listed as being 25 years of age and valued at $800. In the 1830s there was severe economic hardship that culminated in the Panic of 1837 which caused the bursting of a land bubble and the collapse of cotton prices. This did result in a decline in the values of enslaved peoples but around the time of Benjamin Temple’s death, the values in enslaved people did start to rebound.

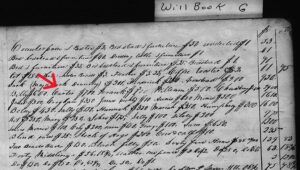

Court document listing the enslaved to be divided among the children of Benjamin Burnley Temple, image courtesy of familysearch.org.

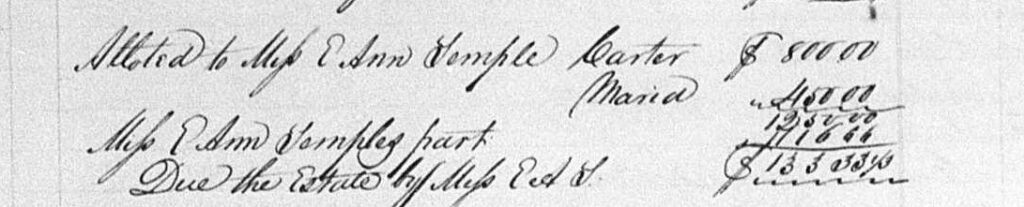

In the division of the enslaved of Benjamin Temple, his daughter, Elizabeth Ann Temple, received Carter Sr. and an enslaved woman named Mariah. The division of the enslaved people among Benjamin’s children was not unusual. This practice, the splitting up of and dividing of enslaved families, was common during the time of slavery in our country, t. Sometimes these families would still remain in the same areas and would be close enough that they could still visit loved ones on neighboring plantations. Not the case for Carter Sr. Elizabeth Ann Temple would marry an English Episcopal Minister named George Beckett and Carter would have been forced to go wherever they went. Not long after Elizabeth married George Beckett, they would first move to Christian County, Kentucky, two counties to the west of Logan County. They would then go on to move to Jefferson County, Kentucky in the northern part of the state where the state capital of Louisville was seated.

Court document showing Carter Temple Sr. and an enslaved woman name Maria being given to Elizabeth Ann Temple, Benjamin Burnley Temple’s daughter, courtesy of familysearch.org.

After being given (it’s still hard to hear these terms being used, but this is the truth of history) to Elizabeth Ann Temple, the whereabouts of Carter Temple Sr. are hard to track. It is unknown when or where he was emancipated. To date, no documentation has been found on his further movements past 1838 or for his emancipation. As previously mentioned, he had children with an enslaved woman named Sarah Hayden. The children Carter Sr. likely had with Sarah were: Fred Hopkins, Lucy Hayden Walker, Frank Hayden, and Carter Temple Jr. (aka Carr Hopkins and Carter Hayden). This gets really confusing at times with the names of the children of Carter Sr., but this is part of the complexity of enslaved families, the naming of children depending on who enslaved you. Who Sarah Hayden was and who she was enslaved by is also confusing. It is a likely possibility that she was owned by an enslaver named Samuel Hopkins, who owned Carter Temple Jr. as evidenced in his deposition for a Civil War pension.

Carter Temple Sr. would also father a child, Victoria, with an enslaved woman, possibly named Victory Carter. Victoria was born in August 1844 in Logan County, Kentucky. She would go on to marry Lemuel “Lem” Low and died in Warren County, Kentucky on June 5, 1916. I am acquainted with Kathleen Lowe of California, a great granddaughter of Victoria Low. Research is still being conducted to verify some of the information regarding Victoria and who her mother really was.

Finally, Carter Temple Sr. would marry a woman named Amanda and would have two more children with her, George and Florence. Another common occurrence among enslaved people is that enslavers would use them as breeders to grow their enslaved populations since the slave trade was outlawed in the United States on January 1, 1808. This is one of the ways that slavery was allowed to continue and grow throughout the United States. It was not uncommon to see an enslaved man or woman have multiple partners and children with more than one spouse. As families were split apart and moved to other locations, enslaved people would have to form new bonds and relationships when they were either sold off or divided as a result of the deaths of their original enslavers. Such was the barbarity of the institution of slavery; the splitting up of families, torture, heartbreak, lost loves, lost connections, no freedom, every aspect of your life being controlled by your enslavers, and laws that restricted every facet of your being.

There was light at the end of the tunnel for Carter Temple Sr. With the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863 and the end of the Civil War, Carter was able to gain his freedom, though the exact date of when he obtained his freedom is unknown. Almost immediately following the conclusion of the Civil War, Carter Sr. moved to Indianapolis, Indiana and bought a house on Minerva Street. Many of the Temple family would live in this neighborhood for many years. In the 1880 Census, Carter Sr.’s occupation was listed as a carpenter. Likely a trade he had learned during his time of enslavement. Carter Temple Sr. died in Indianapolis, July 6, 1888. Before his death, Carter Sr. was able to do something that he was not allowed to do as an enslaved man, make out a will. His will, recorded July 14, 1886 reads as follows:

Know all men by these presents that I Carter Temple S. being possessed of of sound mind do hereby make this my last Will and Testament

First. I bequeath and desire to my wife Amanda Temple, House and Lot described as follows. Lot 59. Out Lot 156. Elliotts’ subdivision situated in the City of Indianapolis Marion Co Ind. To have and to hold the same during the remainder of her natural life. Should at any time my wife Amanda Temple desire to sell said property then my wife Amanda Temple is to have the privilege of so doing When the property is sold whether before the death of my wife Amanda Temple or during her life time then the said Amanda Temple is to have one third of the receipts from said sale and the remaining two thirds is to be divided among the children as herein after stated I desire my wife Amanda Temple to have all of my personal property including household goods and utensils except my carpenter tools

Second I desire my daughter Victoria Lowe now living in Logan Co. Ky to have Ten Dollars ($10.00) out of the amount received for the house and lot when sold

Third I desire my son Frederick Hopkins now living in Vicksburg Mississippi to have Five ($5.00) out of the sale of my Real Estate.

Fourth I desire my daughter Lucy Walker to have twenty dollars out of the sale of my Real Estate

Fifth I desire my son George Temple to have ($75.00) out of the sale of my real estate

Sixth I desire my son Carter Temple to have fifty dollars ($50.00) out of the sale of my real estate

Seventh I desire my daughter Florence Watts to have all that is left from the sale of my real estate after the above provisions have been carried out

Eighth I desire my son Carter Temple to receive my hand tools.

Ninth I desire my son Carter Temple to be Administrator of my estate.

In testimony whereof I have hereunto set my hand and seal this the Fourteenth day of July 1886 City of Indianapolis Marion County State of Indiana

Carter his x mark Temple

What were Carter Temple Sr.’s hopes and aspirations in life? What unthinkable horrors and tragedies was he subjected to as an enslaved man? How did he feel when he was separated from his family in 1838 when the enslaved people of Benjamin Burnley Temple were divided up amongst his children? One thing we can all be sure of is that Carter Sr. probably yearned for his freedom. After reading his will, it is without a doubt that he very much loved his family. After all, he did provide for each and every one of them in his will. Despite living much of his life enslaved, he did see a day where freedom became his and for those he loved. He saw a day where he was able to be reunited with, or aware of where all of his children were. His legacy is the many talented descendants who came after him, descendants who achieved and are still achieving many great things. He has left a legacy of military service members, artists, lawmen, actors/actresses, all things that his blood, sweat, and tears were shed to make come to pass. We do not know what Carter Temple Sr. looked like, but we do have an account of his appearance. From the deposition of Oliver Wright, a man who worked in carpentry with Carter Temple Jr. from 1866-1870, Wright states that, “I knew his father, his name was Carter Temple and he always recognized/claimed him as his son. And they were very much alike in appearance and disposition.” One of the most poignant things Cecelia Boler, Carter Temple Sr.’s great great granddaughter, told me was “This is the only description I have of Carter Sr., but I’m so grateful for it.”

Carter Temple Jr. and his life, through his words

When I typically write, I am usually writing about little-known people from history, who do not leave their own words, accounts, diaries, journals, etc. I am usually researching and deep diving into the documented history to craft narratives around the subjects I take on. Carter Temple Jr. was a Civil War veteran who served in the 14th United States Colored Infantry. As such, later in life, he applied for and received pension for his service and disabilities he incurred as a result of his service. To receive his pension, he had to make depositions and get supporting depositions from others to receive his veteran’s pension. Cecelia Boler, great granddaughter of Carter Temple Jr., provided me with copies of two of his depositions. In these depositions, he provides a lot of great and valuable information that sheds light on his life. It is not often that records such as this are put out in the public sphere, and as such, I felt compelled to let Carter Jr. tell his story, rather than me write a biography of him. There are a few articles that have been written on Carter Temple Jr. and the Temple family of Indianapolis, one of which I highly recommend others to read; https://invisibleindianapolis.wordpress.com/2018/10/16/visual-memory-and-urban-displacement/. To my knowledge, Carter Temple Jr.’s depositions have never before been published, so here we go, his story, his words.

“Once let the black man get upon his person the brass letters US, let him get an eagle on his button, and a musket on his shoulder, and bullets in his pocket, and there is no power on earth that can deny that he has earned the right to citizenship in the United States.”—Frederick Douglass, 1863

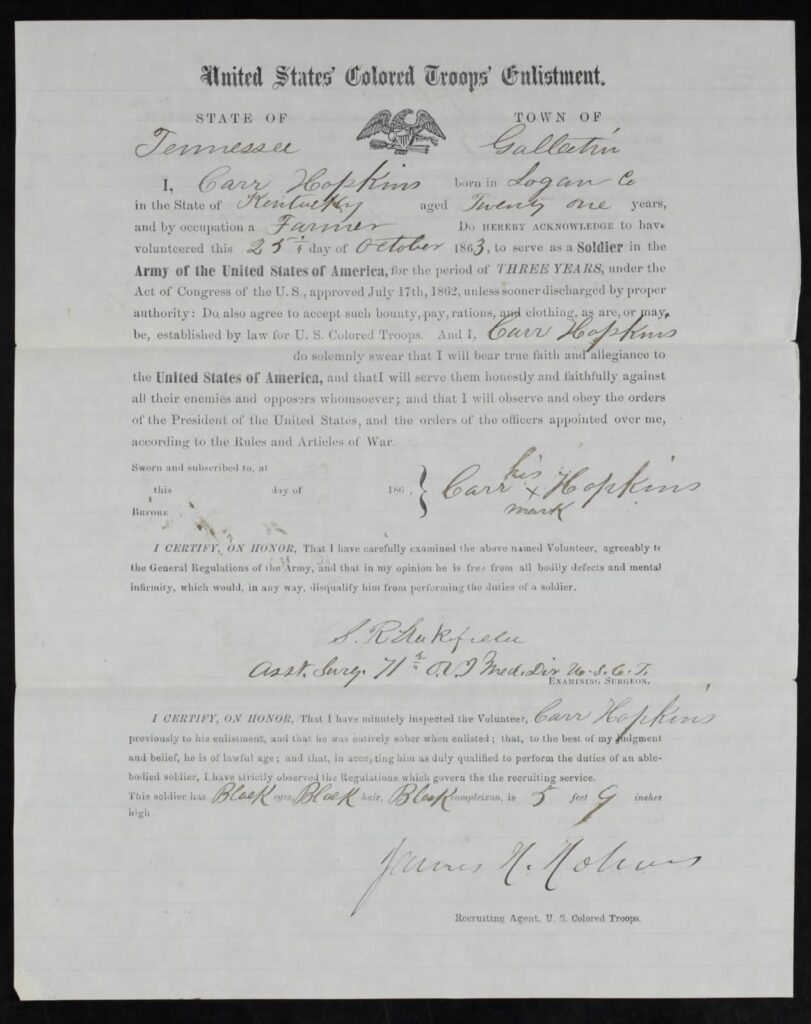

Pension Deposition of Carter Temple Jr., January 1, 1891

[I] am 47 years old, am a Policeman; my residence and P.O. address is No. 182 Minerva Street, Indianapolis, Ind. have lived in this City and right near the City since 1866. My name is is Carter Temple Jr. I am the same person who enlisted in Co. C 14th U.S. Cold Inf. under the name of Carr Hopkins, and served from Nov 1, 1863 to March 26, 1866. I also enlisted as teamster in Co A 106th Ohio Mounted Inf in Aug 1863 and served to about Nov 1st 1863. I never served in any military or naval organization other than the ones mentioned. Prior to my enlistment I always lived near South Union, Logan Co. Ky. I was a slave and was owned by Samuel Hopkins of that place and I lived with him until I run away and joined the 106th Ohio Inf in Aug 1863. Always prior to my enlistment I bore the name of Carr Hopkins and I continued to bear and to be known by that name, until about spring of 1866. After I came to this City when and where I found my father who was then known and recognized by the name of Carter Temple, and from that time I took up his name, and have ever since been known and recognized as Carter Temple Jr. My father is dead. He died July 6, 1888. My mother [Sarah Hayden] died when I was 10 years old. At and prior to the commencement of war, my Father was owned and lived with a man by name of Becket, who lived at Hopkinsville, Ky until about 4 or 5 years prior to the commencement of the War. When Becket moved to Louisville, Ky. and took my Father with him. After my Father went to Louisville, Ky with Becket I saw him only once, before I saw him at this City in spring of 1866 and that was in year 1859 or 1860. My Father went by the name and was called Carter Temple while he lived with Becket. My Mother lived with Samuel Hopkins, my old Master, and my Father used to come and see us once a month, until he went to Louisville Ky with Becket and at time of her death she was living with Hopkins. Prior to my enlistment I was always a strong, healthy person, and never had any ailments or sickness that ever laid me up.

While I was a member of Co C 14th U.S. Cold Inf. I contracted pleurisy and neuralgia at Decatur, Ala. about Oct. 1864 brought on by exposure lying out in the rain and wet there. We had been fighting all day and making charge on General Hood and I became over heated in that fight and that night while lying on the ground the River there rose and came over us, and I was thoroughly wet, which caused me to take cold, producing neuralgia and pleurisy. The neuralgia affected the left side of my head, left ear and my eyes. I had severe pains in my head and left side of my body…Right away after I was attacked with these disabilities and when we reached Chattanooga, Tenn. I attended sick call and received treatment from Surg. Fisher Ames and Asst. Surg Willard H. Green and they treated me at different times after that as long as I was in the service. I did not go to any Hospital. I was relieved from duty nearly all the winter of 1864 and 1865. I don’t know where these surgeons are now. I never could find out. I never contracted any disability other than the ones mentioned while I was in the Army, except diarrhea, which I had at Knoxville, Tenn. in July 1864. I recovered from the diarrhea after my muster out of service. I came to this City where I have since resided and I have suffered from the neuralgia every year, and the pleurisy in left side about every other year or so…I was treated for these disabilities by Dr Bluebaker [?] then of this City; but present whereabouts unknown. He treated me in the spring of 1866 and prescribed for me 2 or 3 times, and Dr. Fletcher of this City treated me in 1866 & 1867 and Dr. Burham, then of this City, afterwards of St. Louis, Mo. treated me in 1867 or 8. Dr. Hunt of this City, whereabouts unknown, treated me about the year 1869. Then Dr. O.S. Reynolds of this City commenced to treat me and at times, ever since, and at times Dr. Hodges has treated me the last 7 years. These are the only doctors that have treated me since I came out of service.

About 1871 or 1872, my left ear commenced to be affected and the hearing impaired while I was recovering from an severe attack of the neuralgia and my eyes commenced to be weak at some time and I have been hard of hearing in my left ear and my eyes have been weak ever since, and are growing worse each year.

I have had 2 severe attacks of neuralgia each year since I came out of service and have had attacks of the pleurisy about every other winter. The neuralgia has always affected the left side of my head, even at times it gets [word illegible] other side of my head…

I cannot furnish the names of any other witnesses in addition to these who have already [word illegible] to establish my claim.

I have been disabled about ½ each year since I came out of Army by reason of these disabilities.

I do not wish to be rectified of any further examination and do not desire to be present when my claim further examination of my claim. Fully rendered and [word illegible] questions and answers thereto are correctly recorded in this deposition.

[Signed] Carter Temple Jr.

Deponent

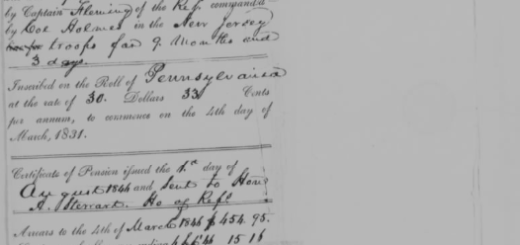

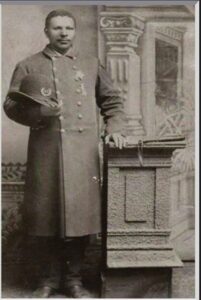

Carter Temple Jr.’s 1863 enlistment document for the 14th United States Colored Infantry, courtesy fold3.com.

Pension Deposition of Carter Temple Jr., December 28, 1920

I am 77 years old. I am a retired policeman. My address is 550 Minerva street, Indianapolis, Ind. I am the same Carter Temple who served under the name of Carr Hopkins in Co. C, 14th U.S. Inf., from Nov. 1st 1863, to March 26, 1866. That was the only service I ever had in the army or navy of the U.S., and I was never in any other branch of the U.S. service. I show you my original discharge certificate and my commission as corporal. I now get a pension of $50 per month under Cert. No. 559400. I had no relative in the War of 1917. I was born in Logan Co., Ky., Nov. 13, 1843. My father was named Carter Temple. My mother was Sarah Hayden. I fell to the possession of Sam Hopkins, and that is how I came to go into the service under the name of Hopkins. After the war I took my father’s name. I have a half brother living. He is George Temple and he is here in Indianapolis. I have no sister at all.

I have never been married but once. I married her, Martha A. Blackwell, a single girl, here in Marion Co., Ind., April 13, 1871, an we have lived here together without separation or divorce ever since and she is now my wife. We have had five children, but all are dead but one. He is Carter F. P. Temple, and he was our youngest child. He was born Feb. 17, 1879. I came to Indianapolis on March 27, 1866, immediately after my muster out and I have lived here ever since. I lived in Logan Co., Ky., 10 miles from Russellville, till I enlisted, and I lived on the farm of my owner, Sam Hopkins, and I left that farm to enlist. I had no wife in slavery and lived with no woman at all until I married my present wife. I was not quite 21 years old when I enlisted. I ran away from Logan Co., Ky., and went to Tennessee and got with the 106th Ohio Inf., and I drove a team for them till November when I enlisted in the 14th. No, I was not an enlisted man in the 106th, but they promised me pay for that work as teamster, but I never got any pay for it at all. It was Co. A, 106th Ohio, that I was with. I was there as Carr Hopkins too.

I have heard this read and it is correct.

[signed] Carter Temple Jr

Deponent

Carter Temple Jr.’s pension depositions in themselves tell a story of his life. One of the things that sticks out to me is how much he mentions his father in the 1891 deposition. Carter Sr. figures quite prominently in this document. Carter Jr. must have really felt a close bond with his father, despite the distance between them during their times of enslavement. When you read about Carter Jr.’s recollections of his father coming to visit him and his mother once a month, you can almost feel that these moments were very much cherished by him. During the time that slavery had a hold on the many millions of enslaved people in this country, families did not get much time together, especially in cases such as the Temple’s where members of the family resided on different plantations. Despite only being allowed infrequent visits, this did not lessen the family bonds with father and son. As soon as Carter Jr. was mustered out of service at the conclusion of the Civil War, he went straight to Indianapolis where his father was and he immediately changed his name to that of his father, showing how close the two were. When Carter Sr. was taken with his enslaver, George and Elizabeth Ann Temple Becket to Louisville, it had to have crushed the family, as the father and son would not see each other again until after the Civil War. In the colonial and antebellum periods, this was a common occurrence, the splitting apart of families when either members were sold off or taken to another location farther away. There were many cases in which enslaved families were never again reunited, but thankfully the Temple’s were one of the instances where a formerly enslaved family were able to be reunited.

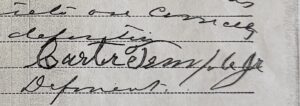

One of the first things I noticed though when I quickly skimmed Carter Jr.’s depositions was his signature at the end of both documents. When he enlisted in the 14th United States Colored Infantry in 1863, he could not sign his name, but only did so by making his mark with an “x” on his enlistment document. In the time between his enlistment and having made his depositions for his pension, Carter Jr. had learned to read and write. It is known that the regimental chaplin, William Elgin, taught many of the men in the regiment how to read and write to help them in the future after their service. When I sent a message to Cecelia Boler about his pension record I said to her, “that’s his signature [Carter Jr.’s at the bottom of the documents]. He could sign his name. He learned to read and write.” Cecelia responded saying, “Yep! My mom said that he would often write things for people who couldn’t.” This shows that Carter Jr. was a man who cared for others and wanted to help others who could not read or write. Additionally, Cecelia stated “My aunt Helen was interviewed in the 80’s and she said that Carter Jr. learned to read and write while enslaved because his mother was the cook in the house.”

Carter Temple Jr.’s signature from his 1891 pension deposition, image courtesy of Cecelia Boler.

In reading of his Civil War experiences, quite a few things sparked my attention and got my thoughts percolating. Carter must have really had a deep yearning to become free, as he emancipated himself in 1863 when the best opportunity presented itself. He made his way to Gallatin, Tennessee where he enlisted in the 14th United States Colored Infantry on November 1, 1863. The regiment at it’s peak strength numbered 950 men, all but eight of whom were formerly enslaved. Carter was promoted to Corporal on April 30, 1864, a high honor and a testament to how good of a soldier he must have been. Black soldiers could not be officers, but they could be non-commissioned officers in the Union Army.

Carter gets promoted to corporal, image courtesy of fold3.com.

There were three major battles or engagements that the 14th was involved in: 1) Second Battle of Dalton (Georgia), August 14-15, 1864, 2) Battle of Decatur (Alabama), October 26-29, 1864, and 3) Battle of Nashville, December 15-16, 1864. Carter was present for Dalton and Decatur, but missed Nashville due to being ill that winter. In researching the battles the regiment was involved in, I came across some accounts of the regiment and their character. This regiment and the men in it, became among one of the best regiments of the Civil War, and not just among Black regiments, but among all of them, and Carter was a part of that, and was likely a point of pride for him, which can be seen in the few images of him. He seemed to be a man proud of what he fought for in the Civil War, and of the accomplishments he achieved in his life.

Document showing where Carter Jr. was deducted 65 cents from his pay for a lost haversack. During the Civil War, if a soldier lost any of his gear, he could be subjected to a deduction in pay as the lost gear was United States property, image courtesy of fold3.com.

As regards the 14th United States Colored Infantry, the Pennsylvania Association for the Relief of East Tennessee made the following report describing the regiment:

At Chattanooga we saw a negro regiment, the 14th U.S.C.T., Col. T.J. Morgan, of Indiana, commanding. It had been raised in Gallatin, Tennessee, ‘a regular secession hole’ as it was described to us, and numbered 950 men, every one of whom, save eight, had been a slave. Their camp was the cleanest we had ever seen, and their appearance and drill unsurpassed. The colonel has full confidence in their fighting qualities, and one of the captains remarked that they could not fail in action with such stuff as their men are made of. The chaplain teaches them three hours a day, and many can read and write [I wonder if this is where Carter Jr. learned to read and write?]. The sight of that regiment on dress parade, with every head bare to heaven as the chaplain lifted up his voice and prayed that they might be strong and quit themselves like men in the day of battle, was one never to be forgotten.

Following the Second Battle of Dalton, regimental commander, Colonel Morgan stated that the “regiment had been recognized as soldiers…After the fight, as we marched into town through a pouring rain, a white regiment standing at rest, swung their hats and gave three rousing cheers for the 14th Colored…” Following the Battle of Nashville in December 1864, Colonel Morgan said, “When General Thomas rode over the battle-field and saw the bodies of colored men side by side with the foremost, on the very works of the enemy, he turned to his staff, saying: ‘Gentlemen, the question is settled; negroes will fight.’”

During his time of service, Carter Temple Jr. experienced what most Civil War soldiers experienced, bouts of sickness brought on by the conditions of life lived by a soldier. Disease ran rampant throughout the Civil War. Disease, the leading killer in the American Civil War, claimed approximately two-thirds of all deaths during this struggle. Even though accounts state that the 14th U.S. Colored Infantry kept one of the cleanest camps, that did not mean that disease was absent from their camp. The life of a Civil War soldier was harsh. Times where nutrition was not sufficient enough when on the march, immune systems were left susceptible to a myriad of diseases and illnesses.

In Carter’s case, when being out in the elements in a wet environment for an extended period of time, he developed neuralgia and pleurisy, both of which affected him for the remainder of his life. Neuralgia is characterized by intense, sharp, burning, or electric shock-like pain caused by damaged or irritated nerves. The pleurisy Carter developed, is the inflammation of the pleura, the thin membrane lining the lungs and chest cavity. Pleurisy is often caused by viral infections, pneumonia, or autoimmune diseases and is typically resolved with treatment of one of these underlying causes. Having lived the hard life of a soldier and constantly being out in the elements and campaigning, Carter likely had developed a viral infection or pneumonia over the course of time and being in wet conditions such as he was following the battle at Decatur, Alabama, he developed pleurisy and had to deal with it for years after his Civil War service. Medicine being what it was then, he likely was not diagnosed with any of the conditions that could have caused the pleurisy and did not receive the proper treatment that he would have received in a more medically advanced time period.

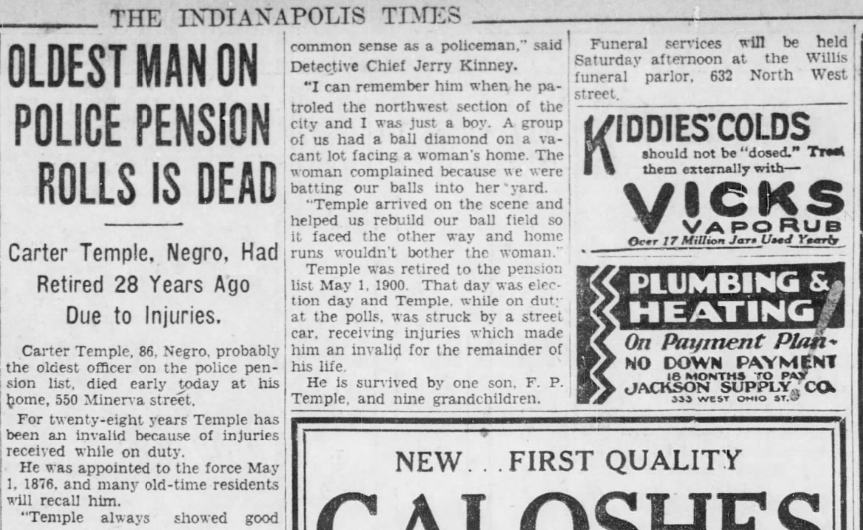

Following his Civil War service and immediate relocation to Indianapolis to find his father and family, Carter worked for several years as a carpenter. In May, 1876, Carter Temple Jr. joined the Indianapolis Police Department (IPD) as one of the first, if not the first, Black police officers in the IPD, one of four to do so along side him. An interesting item to note, prior to becoming a police officer, he aspired to become an actor, but after having performed in one minstrel show, he applied to become a policeman instead. His aspiration of becoming an actor would be realized, not by him, but by his great granddaughter, Cecelia Boler. Cecelia has worked in TV, film, commercials, and done voice overs. Her most notable acting role was in Chicago P.D. when she played the role of a medical examiner. Carter Jr. married Martha Blackwell April 13, 1871, and they went on to have five children, only one of which survived them, Carter F.P. Temple. Carter Jr. had two daughters, Christina who lived to seven years of age, and Martha who lived into her 20s. Two of Carter’s sons died in infancy, one in 1872 and the other in 1874. Carter Jr. was forced into retirement in 1900 after being struck by a streetcar on election day in that year.

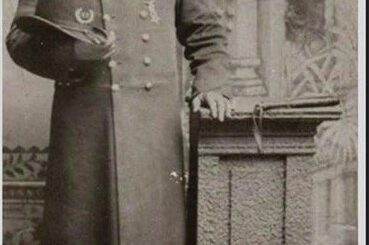

Carter Temple Jr. after joining the Indianapolis Police Department. He was one of the first African Americans, if not the first to join. Image courtesy of Cecelia Boler.

Carter Temple Jr. died, aged 85 years, on February 14, 1929, in Indianapolis. He was buried at Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis. See the below image of the announcement of his death in the Indianapolis Times edition for February 14, 1929. Like his father before him, Carter Jr. was born into slavery. But he broke those chains, self-emancipating himself and joining the struggle to end slavery through force of arms. He went on to relocate his family, settle, have a family of his own, a career, and lived a long life. One more fully lived than most could say. His character was marked as one of near flawlessness. He was one who cared for others and wanted to help others and leave a positive mark on those he encountered. He was a man who was capable of enduring the most grueling of hardships and despite the circumstances he started out life in, he rose to accomplish great things and, most importantly, he ended life as a man able to make decisions and choices as he saw fit. He embodied what the Black man was capable of achieving, despite what many who thought people of his race could accomplish. Cheers to Carter Temple Jr., the embodiment of what a true hero is, of what an American is and should be. And his legacy, numerous descendants who carry the same strength, courage, and honor and an ability to achieve the things they set their minds to.

Announcement of the death of Carter Temple Jr. in the Indianapolis Times, February 14, 1929. Image courtesy of newspapers.com.

Gravestone of Carter Temple Jr., Crown Hill Cemetery, Indianapolis, Indiana.

References

Ancestry.com, 1880 United States Federal Census (Year: 1880; Census Place: Indianapolis, Marion, Indiana; Roll: 295; Page: 442a; Enumeration District: 120), Ancestry.com Operations Inc., Lehi, UT, 2010.

“Logan, Kentucky, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33SQ-GPSR-9B4R?view=explore : Feb 8, 2026), image 41 of 621; Kentucky. County Court (Logan County).

Mullins, Paul. Visual Memory and Urban Displacement, Invisible Indianapolis, October 16, 2018, accessed February 8, 2026, https://invisibleindianapolis.wordpress.com/2018/10/16/visual-memory-and-urban-displacement/.

“Russellville, Logan, Kentucky, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9P9Z-DML?view=explore : Feb 8, 2026), image 486 of 1485; Kentucky. County Court (Logan County)

Temple Jr., Carter, January 1, 1891, Deposition of claimant, Carter Temple, Jr., Co. C, 14th United States Colored Infantry, certificate number 614952, Case Files of Approved Pension Applications, 1861-1934, Record Group 15, NARA, Washington, D.C.

Temple Jr., Carter, December 28, 1920, Deposition of claimant, Carter Temple, Jr., Co. C, 14th United States Colored Infantry, certificate number 559400, Case Files of Approved Pension Applications, 1861-1934, Record Group 15, NARA, Washington, D.C.

The Indianapolis Times; Publication Date: 14 Feb 1929; Publication Place: Indianapolis, Indiana, USA; URL: https://www.newspapers.com/image/873608521/?article=3d22a930-0478-421d-9b93-9cf51d83bd70&focus=0.38491747,0.040937576,0.50093424,0.19936433&xid=3355