Anne Catherine Spotswood: A woman ahead of her time

Colonial Virginia history has many women who hold a place in this Commonwealth, some well-known, but many who are not. One such woman who holds an important place among Virginia’s colonial history was Anne Catherine Spotswood. Born in 1728 in London, England, she was the daughter of Virginia’s former colonial Lieutenant Governor, Alexander Spotswood, and his wife, Butler Brayne. Little is known of Anne Catherine though. During the Civil War, Richmond burned in April 1865 at the end of the war and King William County’s courthouse burned shortly after the Civil War. These two events wiped out many of Virginia’s colonial records. Documentary accounts of her are almost non-existent due to the loa of records. Imagine the wealth of information that could have been gleaned, not just on Anne Catherine, but many of Virginia’s important people and events. Personal accounts of her are few, but they are revealing of her character.

One of Virginia’s most famous and well-known colonial governors, Alexander Spotswood had lived a busy life full of danger, adventure, and politics. When he was replaced as Lieutenant Governor in 1722, at the age of 46, he was still a bachelor, a very old age for the time to still be unmarried. Shortly after being replaced, he went back to England in search of a wife. On March 11, 1724, Spotswood married Butler Brayne at St. Marylebone Church in London.

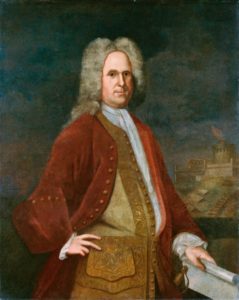

Lieutenant Governor Alexander Spotswood, portrait by Charles Bridges.

Born in 1728, Anne Catherine Spotswood became the second child born to Alexander and Butler Brayne Spotswood. Her siblings were John (born about 1724), Dorothea (born about 1732) and Robert (born about 1734). Anne Catherine was baptized October 19, 1728, at St. Luke’s Church in Chelsea, London, England. Little is known of her early life. The family went back to Virginia in about 1730 and settled in Spotsylvania County, which was formed in 1721 and named after Governor Spotswood. The former governor owned over 80,000 acres in Spotsylvania and established his family in the county at his home known as the “Enchanted Castle”. There Spotswood set up the first county seat.

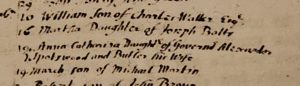

Anne Catherine Spotswood’s baptismal record, courtesy of Ancestry.com.

It is not known what kind of early education Anne Catherine received. However, the Spotswood family was a very wealthy family, and it is safe to say Anne Catherine and her siblings were probably well educated. Their wealth would have allowed the Spotswood’s to pay tutors to come to the family home and instruct the children. Typically, women of the period only received basic education in reading, writing, and arithmetic. Sometimes they would also receive education in other languages, usually French or Latin. If a family was very well off, they may have their daughters taught other subjects that sons in the family would receive. Women were also taught to play some sort of a musical instrument, dancing, and attained a learning in polite and proper social manners. As well as this education, women in the upper crust of society would also learn at an early age all that they would need to know how to become a wife and run a house and plantation. Though no known records exist as to how well Anne Catherine was educated, an account of her was left by her grandson, Colonel John Spotswood Skyren. Having known his grandmother well, Colonel Skyren had this to say of her:

“I saw much of my grandmother, Mrs. Anne Catherine Spotswood Moore. She did not die until I was in my twenty-third year. She was a very intellectual woman, and well posted on almost every subject. She was a good genealogist, and took much interest in the history of her own family and that of her husband; and had a little leather bound book in which she had written many things concerning the Spotswoods and the Moores…She would let me read this old book concerning my ancestors, and promised to leave it to me, as I also was interested in genealogy; but I never saw it after her death.”

In a time when education was lacking for women compared to men, Anne Catherine seems to have been a well-educated woman who could hold her own in any number of conversations, whether it be between men or women, or both. Her being “well posted on almost every subject” and being well educated would serve as a catalyst for her to be able to have an independent mind and to think for herself and have her own opinions on matters.

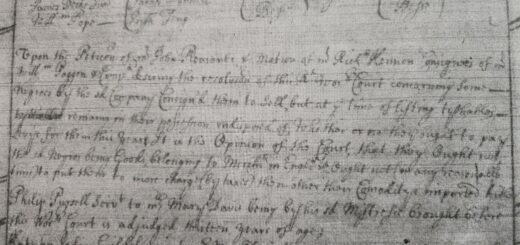

Governor Spotswood died June 7, 1740, when he was embarking from Annapolis, Maryland with an expeditionary force of colonial soldiers to take part in the failed attack on Cartagena in present day Colombia. His death did not leave the family in dire straits though. He left a massive, landed estate, the value of which was enormous. In his will dated April 19, 1740, Spotswood left to his daughter “Anna Catherina the sum of two thousand pounds sterling to be paid to her at her age of twenty one years or day of marriage, wch shall first happen and to be raised by mortgage or sale of any my lands herein before devised”.

Along with this legacy, he left the family a connection that would have a big impact on Anne Catherine’s future. In 1716, Governor Spotswood led his Knights of the Golden Horseshoe on a trip of discovery over the Blue Ridge Mountains. The expedition set off from Chelsea in King William County, Virginia. The plantation was owned by Colonel Augustine Moore. It has been said that it was at Chelsea that Governor Spotswood concocted the name for this expedition of the Knights of the Golden Horseshoe. Through this link to the Moore family of Chelsea, a courtship between Anne Catherine and Augustine Moore’s son, Bernard Moore, began. The couple were wed in the early 1740s.

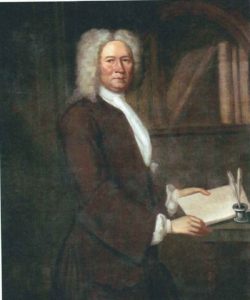

Colonel Bernard Moore, painting by Charles Bridges.

As was common in British society in this time period, upon marriage any land, money, and possessions that belonged to the wife became the property of the husband. So, any lands that Anne Catherine inherited from her father in Spotsylvania and the money he had bequeathed to her became Bernard’s. In some instances, as part of a marriage arrangement, a wife could keep ownership of anything she owned, but this did not occur in this case. If a husband died, the widow could regain ownership of all land, possessions, money, and slaves or have a lifetime tenancy of such.

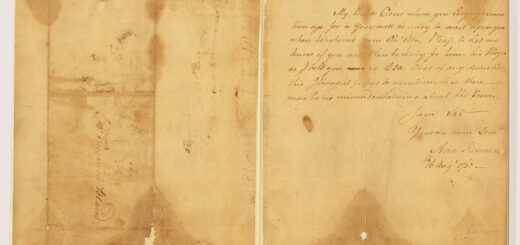

There is no known will to be in existence for Bernard Moore, Anne Catherine’s husband, as loss of records prevents us knowing what provisions he made for her in the event of his death. Despite this, Anne Catherine must have been very highly regarded by Augustine Moore and his family. In his will dated January 20, 1742, Colonel Moore made a number of bequests to her:

“But my will & desire is, that if my Daughter-in-Law, Anne Moore, should be left a Widow, she should have the Land whereon her Husband now lives & five hundred acres of that Land given him in Spotsylvania, during her life…But it is further my Will, that my Daughter-in-Law, Anne Moore, shall be left a widow, she shall have the use of Ten working slaves, such as she shall choose out of the part given my said son Augustine, during her life.”

Bernard and Anne Catherine Spotswood Moore would eventually settle themselves at Chelsea in King William County. Throughout their marriage, they would have eight children: (1) Augustine, (2) Thomas, (3) Bernard Jr., (4) Elizabeth, (5) Lucy, (6) Anne Butler, (7) John, and (8) Alexander Spotswood. With such a large and growing family, Bernard had the house at Chelsea expanded with an additional wing added to the back of the original house.

Side view of Chelsea showing the addition added by Bernard Moore, photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Not many accounts of Anne Catherine’s domestic life at Chelsea exist. As was common of women in the colonial era, Anne Catherine’s purview was the house and everything in it. She was responsible for the organizing and tasking of the slaves in the home and their daily routine. Sometimes women would take part in assisting in jobs and tasks involved in the home. Colonial women would brew beer, help in preparing meals (especially if it were a big meal if there was an event or gathering at her home), sewing, tending to gardens, and tending to the sick on her home plantation. Despite all the things women in colonial days were responsible for, if she were a well-off woman, she would still be expected to maintain the appearance of a life of leisure. Knowing the character of Anne Catherine, passed down to us through accounts of her, she likely was a woman who was a hands-on house manager. For the education of the children, she and Bernard hired the Reverend Henry Skyren. Reverend Skyren taught the Moore children, and likely other children from adjoining plantations, at Chelsea in a small schoolhouse which still stands today. Reverend Skyren would go on to marry one of Anne Catherine’s daughters, Lucy.

Anne Catherine’s father-in-law, Augustine Moore, was heavily involved in the slave trade. He served as a colonial agent for the English firm of Isaac Hobhouse and Company out of Bristol, England. The company was involved in the triangle trade of slaves from Africa to the colonies, sugar from the Caribbean and the transport of tobacco to England from the colonies. The Moore’s at Chelsea owned a large number of slaves and as an agent for Isaac Hobhouse, Augustine sold slaves at Chelsea as the location had a wharf for small boats to dock at carrying its human cargo. Archaeology at Chelsea has recovered slave tags and a pair of shackles once worn by slaves. The role Anne Catherine played in slavery is in having managed them on the plantation and in the house. Only one account of her interactions with slaves was given by her great-grandson, Charles Campbell, in his book Genealogy of the Spotswood Family in Scotland and Virginia. In his book, Campbell speaks of an incident of “her having made her negroes toss an overseer who had offended her, in a blanket, while she stood at a window to witness the scene.” Aside from this account, there is no known record of how life for her slaves at Chelsea went or how she and the family treated them.

Though Anne Catherine was a domestic housewife, she, like her father, did experience danger and adventure. Charles Campbell relates a story about her in his book that attests to her strength and fortitude: “Once when her husband was absent, being at Hanover Court House, on a bat-shooting expedition, upon a sudden alarm of Indians she ordered up all hands, manned and provisioned a boat, and made good her retreat down to West Point.”

The family, well connected as they were, had many famous friends and visitors at Chelsea. One of these was Thomas Jefferson who was a close friend of the family and visited at Chelsea frequently. He once gave advice to Anne Catherine and Bernard’s son, Bernard Jr., on a course of study in law. Bernard Jr. attended the College of William and Mary in 1760 and again in 1769, though it not known whether he completed his degree. Jefferson, an avid horticulturist, obtained some plants and other garden items from the Moore’s at Chelsea. George Washington also visited Chelsea on a few occasions as the plantation was a good stopping off point on his route to Williamsburg when he was a member of the House of Burgesses.

In 1766, the Moore family fell on hard times. For a number of years, Bernard had invested large sums of money in land speculation and other ventures and lost heavily. He had borrowed large sums of money in his ventures including £1,200 from the estate of Daniel Parke Custis and £8,500 from his brother-in-law, John Robinson, Speaker and Treasurer of the Virginia House of Burgesses. When Robinson died in 1766, it became known that he had been loaning out treasury notes to friends, family and acquaintances. These treasury notes were supposed to have been collected and burned on receipt. The ensuing scandal would put many of his friends, family and colleagues in massive debt. The Moore family in the end would lose much of their land in a lottery that was managed by none other than George Washington. Washington himself purchased some of the lands in the lottery, including Romancoke (some of the money Bernard borrowed was used to purchase this property), for his stepson, Jacky Custis. The family would keep some of the lands surrounding Chelsea and persevered through the difficult times they faced.

After the family got through the storm of financial difficulty, they and all the colonies experienced another, wide ranging tumult and events that led up to the Revolutionary War. Bernard, himself a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses, likely played a big role in the events leading up to our separation from the mother country, as him and most of his family supported the patriot cause. Unfortunately, Bernard died April 15, 1775, just days before the events of Lexington and Concord in Massachusetts. This was probably a big loss for Anne Catherine, for she had been married to Bernard for more than thirty years and weathered many trials and tribulations.

As mentioned, most of Anne Catherine and Bernard’s family supported the push for independence and the cause of the colonies in the Revolution. The one outlier in the family? Anne Catherine herself. Charles Campbell states, “she was a strong adherent of the British government, while her husband and children sympathized with the patriot cause in the revolution. She, as being the daughter of a haughty British governor, persisted in drinking her tea, although a contraband article, privately, in her closet, during the war.” This is significant. In the pre-modern days of woman suffrage and women’s rights, it was usually expected for a woman to keep her thoughts, opinions, and, in this case, loyalties to themselves. She was definitely a woman ahead of her time in that she expressed her loyalties and opinions openly against those of her husband and children who supported the patriot cause. It was usually expected for a woman to support her husband’s and family’s beliefs.

Augustine Moore, painting by Charles Bridges, courtesy of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

There is a family tradition that during the later stages of the war that British troops arrived at Chelsea, went through the house and put to the sword many of Chelsea’s portraits that hung on the walls. It makes one wonder what she thought of the British after this occurred. Despite her support of the British at the outset of the war, her love for her family and the damage done at Chelsea by the British, likely drove her to become a reluctant supporter of the patriot cause. Two of her sons fought in the Revolution. Her son, Alexander Spotswood Moore, served as an aide-de-camp to the Marquis de Lafayette and Bernard Jr. was also involved in the war. Lafayette himself even made Chelsea a temporary headquarters on his way to Gloucester when Continental and French forces cornered the British at Yorktown in October 1781. With the patriot victory at Yorktown and the end of the War for Independence, Anne Catherine became an American.

No known portrait of her exists, only accounts of her given by grandchildren and great-grandchildren. Her grandson, John Spotswood Skyren says that “she must have been very beautiful when young, for she was pretty as an old lady.” Campbell states that she “was elegant in person and manners, and of a high spirit…A granddaughter of hers remembers, when she was a little girl, seeing her sitting up in bed, at Chelsea, combing her white and silken hair, a servant holding up a looking-glass before her.”

By all accounts, Anne Catherine died in 1802, at about the age of 74 or 75, an old age for that time. The whereabouts of her grave, and that of her husband, are unknown. Though she fit the mold of an elite colonial Virginia woman, the strength she exhibited in the few accounts of her life and her independence she exhibited in her life, I feel, places her a little bit ahead of her time. With these few accounts of a little-known woman from 18th Century Virginia history, hopefully a new life portrait will be preserved for future students and scholars of Virginia history.

References

Campbell, Charles. Genealogy of the Spotswood Family in Scotland and Virginia. Albany: Joel Munsell, 1868.

College of William and Mary. A provisional list of alumni, grammar school students, members of the faculty, and members of the Board of Visitors of the College of William and Mary in Virginia, from 1693 to 1888 : issued as an appeal for additional information. Richmond: Division of Purchase and Printing, 1941.

Fontaine, William Winston and Spotswood Fontaine. “Some Virginia Families—Moore, Bernard, Todd, Spotswood, etc.” William and Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine 19, no. 3 (January 1911): 177-184.

Long, Todd Eberle. Voices of the Past: The Long and Brooks Family History. Fullerton, California: Creative Continuum, 2013.

Morgan, Edmund S. Virginians at home: Family Life in the Eighteenth Century. Williamsburg, VA: The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1952.

Thanks, Todd This was very interesting.

Thanks for reading Anne!!!

This article was very interesting! Great job.

Thanks for reading mom!!!

Interesting rticle Todd–I had heard her name, but didn’t know much about her.

Thanks for always reading my articles Dr. Coles, such a great honor to have someone as eminent in the field as you, reading my stuff.

Thank you so much for this article! Anne Catherine Spotswood is my 7th great grandmother; I’m currently working on this branch of my family tree and this article was so helpful!

Eliza, I’m glad the article was helpful to you.

Anne Catherine is my 7th great grandmother. I’m currently researching this branch of my family tree and your article was very helpful!

Very interesting my sister-in-law is Katherine Spotswood Park who has just retired as a professor from Harvard, and she received a gift from her aunt Katherine Spotswood when she was born. Her mother was a Claiborne from Petersburg Va. and her father Professor David Park whose ancestor came on the Arabella.