Dating Colonial Pipes and Pipestems

Tobacco is one of the main reasons that the colony of Virginia became successful and survived past its turbulent early years at Jamestown. Since its founding in 1607, the Jamestown colony had sought to turn a profit by finding gold and other precious metals and find a path to Cathay (what China was called in this time period) and its riches. Dating back to the Roanoke Colony in the 1580s, England had attempted to find gold in the New World. Both the Roanoke and Jamestown colonies sent what they thought was gold ore back to England to be tested. Pun intended, things did not quite pan out in their search for gold or a route to the Orient.

In lieu of failing to find a way to make the Jamestown colony profitable, the Virginia Company, its investors, and the colonists in Virginia made other attempts to find industries or materials to set the colony on a sounder footing. They made attempts at glassmaking, silk making, herbs and medicinal plants, and shipping timber back to England. But none of those industries brought Virginia the profits it needed to succeed. In 1612, things changed for the colony; John Rolfe grew and experimented with tobacco seed that he had brought to the colony from somewhere in the Caribbean. The native tobacco of Virginia was a harsher tasting species, used mainly for ceremonial and medicinal purposes, rather than for pleasure. Rolfe’s new tobacco leaf that he grew “smoked pleasant, sweete and strong.” This was the moment. Tobacco is what finally helped to establish and make the colony what its investors had imagined for it.

Tobacco set things in motion. Initially, small shipments of tobacco were sent to England, and it became extremely popular back home. Tobacco became the cash crop of Virginia and would remain so until the early 20th century. In the colonial era, tobacco equaled money, as Virginia did not have its own currency until the Revolution. Tobacco served as the colony’s currency. Growers in the colony would send their crop to England to be sold at market by agents serving as their factors. The value of the crop would fluctuate based on quality and the market. If the quality was good, then a crop could fetch good prices, unless the market was saturated in which case it could bring less. Planters were not paid for their tobacco in cash. Merchants in England would give credit to the colonists back in Virginia for them to be able to purchase commodities and the things necessary for them to live. This cycle would keep most planters in debt to English creditors as the Virginians would quite often purchase goods worth more than what their crop brought at market.

Another institution that tobacco set in motion was slavery. Slavery existed early on in the colony; the first Africans were first introduced to Virginia in 1619. The institution did not take immediate hold. Initially indentured servitude was what made up the main labor force of the colony. By the later part of the 17th century, indentured servitude declined, and slave labor began its march upward as the demand for tobacco increased.

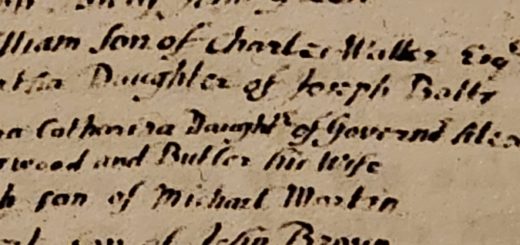

With the growth in the tobacco trade, a fairly new industry grew, pipe making. In 1608, Robert Cotton, a tobacco pipe maker, arrived in Jamestown. Prior to his arrival at Jamestown, the pipemaking industry was controlled by Dorset clay merchants in London. Their pipes were made of a clay that turned white when fired. Cotton used native Virginia clay that turned a reddish to chocolate color when fired. Clay pipe fragments made by Cotton are some of the most ornate and unique. Examples of these pipe fragments can be seen at the Jamestown Archaearium. It is not known how long Cotton was in Virginia as he was not listed in the 1624/25 muster.

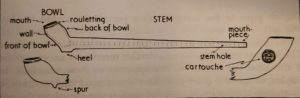

Fig. 1. The parts of a clay tobacco pipe.

The smoking of tobacco in Colonial Virginia was very popular. Obtaining clay pipes was also affordable at all levels of society. For example, in 1709 a clay pipe could be obtained for as little as 2 shillings. Clay pipes and clay pipe fragments are among some of the most abundant artifacts found on colonial sites in the state. These fragments are a big aide in helping to determine the age of a site or when it was most inhabited. When being fired, wires were inserted into pipe stems to create the bore hole through which a smoker would inhale the smoke from the bowl of the pipe. Clay pipes could range in size from 1¾” to upwards of 2’. The stems in the later 16th century tended to be smaller but over time grew in length. The shapes and designs of clay pipes can also tell what time period they are from themselves. In the later 16th through the 17th century, pipe bowls tended to be smaller with wider bore holes. In the later 17th century and onwards, pipe bowls and the length of their stems grew, requiring a smaller wire to create the bore hole to prevent the wire from penetrating the stem.

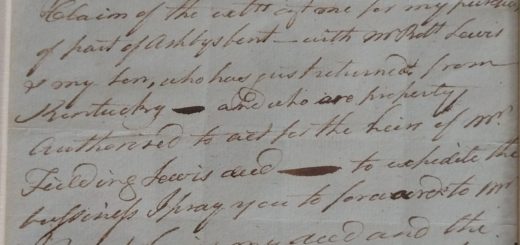

Some clay pipes can be plain, and some have designs to them. The Robert Cotton pipes from Jamestown, for example, contain the names of some of the colony’s most prominent men and some of them have diamond shaped patterns stamped into the stems. Some can have coats of arms or cartouches stamped on the bowl of the pipe. Sometimes pipemakers would stamp their initials on the heel of the bowl or the bowl itself (see Fig. 2). Pipe stems, as mentioned above, could have some kind of design stamped into them, such as a floral motif for example (see Fig. 3).

Fig. 2. A pipe bowl that dates to 1680-1720 showing the initials of the maker. This pipe came from the Hopewell Tavern Site.

Fig. 3. Pipe stem fragment, dating 1750-1800, showing a floral motif. This fragment came from Chelsea Plantation in King William County, Virginia.

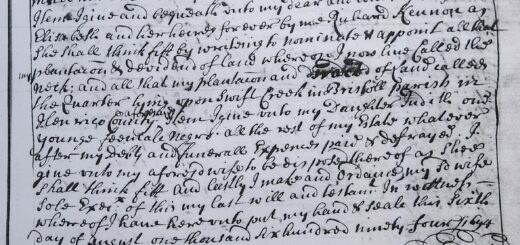

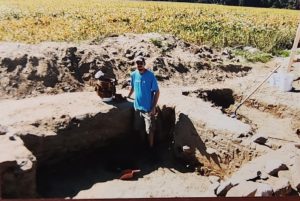

Clay tobacco pipes show up frequently at colonial sites because they, like all other everyday items in the colonial period, became trash. They could be discarded in wells that were no longer being used. Colonists did not have a local landfill or garbage service as we do today, so they would sometimes dig trash pits to discard broken or damaged items, or sometimes, they would just throw stuff out the window. At some sites, a structure may fall into disrepair or no longer be in use, so people would just throw trash into those structures. After graduating from college, I did some volunteer work at Chelsea Plantation in King William County, Virginia in 2009. One of the activities I helped with was the archaeological excavation of a root cellar on the site. During the dig, we uncovered numerous fragments of pipes and pipe stems in the cellar (see Fig. 4). In some cases, trash and clay pipes were discarded in privies. Below are some examples of clay pipes excavated from a colonial tavern site near Hopewell, Virginia (see Fig. 5).

Archaeological dig at a root cellar at Chelsea Plantation in October 2009.

Fig. 4. Clay tobacco pipes and fragments from the root cellar at Chelsea Plantation.

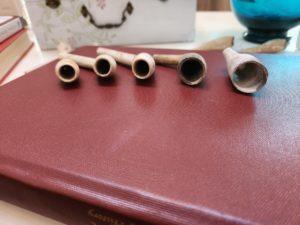

Fig. 5. Clay pipes and pipe stem fragments from Hopewell Tavern Site. Typically, pipe bowls and stems are broken and fragmented. These examples are not commonly found in such good condition on colonial era sites.

Dating colonial pipes is quite simple. One way is the shape of the bowl. Smaller bowls tend to correlate to an earlier date. Larger bowls can tend to suggest a later date (see Fig. 6). The most effective method of dating colonial era clay pipes is the diameter of the bore of the stem, in 64ths of an inch:

Diameter Dates

9/64 1590-1620

8/64 (1/8) 1620-1650

7/64 1650-1680

6/64 (3/32) 1680-1720

5/64 1720-1750

4/64 (1/16) 1750-1800

Fig. 6. Examples of how pipe bowls changed in size over time. From left to right: (1) 1620-1650, (2) 1650-1680, (3) 1650-1680, (4) 1680-1720, and (5) 1720-1750.

The method of measuring the bore hole in a pipe stem to determine its age was created by J.C. Harrington, a long-time archaeologist for the National Park Service. In the 1950s, Harrington studied thousands of pipestems from Jamestown and other historic sites in Virginia, leading him discover the correlation between the size of the bore hole in a pipe stem and its age.

Fragment of a pipe bowl from Chelsea Plantation displaying the letters “ER”.

To measure the bore of a stem, all you need is a drill bit set. Get all the bits for the measurements above, and simply insert the drill bit into the bore hole of the stem. The drill bit that is the perfect fit, will give you the date range of your pipe or stem fragment. If you have a several fragments or a large collection of stems/fragments from a single site, you can use those pieces to determine when a site was most heavily inhabited or in use by a group of people. For example, in my collection I have several pieces of pipes and stems from two colonial sites, Chelsea Plantation in King William County and the tavern site located in Hopewell, Virginia:

Chelsea Plantation

Date Range: Number of pipes/stem fragments:

1590-1620 0

1620-1650 0

1650-1680 0

1680-1720 0

1720-1750 5

1750-1800 1

Hopewell Tavern Site

Date Range: Number of pipes/stem fragments:

1590-1620 0

1620-1650 1

1650-1680 4

1680-1720 1

1720-1750 2

1750-1800 0

Although there are not a very large number of fragments for both sites, this provides enough information to give an example of how one can determine when a site was most heavily inhabited. For the Chelsea Plantation site, there were 5 fragments in the 1720-1750 time period and 1 for the 1750-1800 timeframe. This suggests that the site was most heavily in use in 1720-1750. Not too bad, seeing as the site was established as a plantation in 1705 by Augustine Moore.

Pipe bowl from Chelsea Plantation, dated 1720-1750, showing the letters “TO” stamped into the back of the bowl.

The Hopewell Tavern site had the largest concentration of stems and bowls from the 1650-1680 timeframe with 4. The earliest bowl dates to 1620-1650, showing that the site was inhabited by Englishmen as early as that time period. There are two fragments from 1720-1750, suggesting that the site was still in use. There are no fragments or bowls for the 1750-1800 slot. It could be that the tavern site fell out of use, but with such a small sample group of pipestems and fragments, a larger grouping of samples would be needed. If you have any parts of a clay tobacco pipe, whether it be bowls or stems, grab a drill bit set, and give it a try yourself.

References

Archaeology for Interpreters, National Park Service, accessed 28 September 2022. NPS Archeology Program: Archeology for Interpreters.

Cotton Pipes, Jamestown Rediscovery, accessed 28 September 2022. Cotton Pipes | Historic Jamestowne.

Hume, Ivor Noël. A Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1969.