Benjamin Temple: Virginia’s Forgotten Patriot and Statesman

The Year was 1676. There was much unrest in the colony as supporters of Governor Berkeley, those of Bacon, and natives were going around killing one another. Much of the hubbub was the result of many people looking for a leader of the people to stand up to what was occurring throughout the colony, the lack of Governor Berkeley standing up to defend the colonists. The people found their champion in a young charismatic newcomer, Nathaniel Bacon. My grandfather, your great grandfather, Anthony Arnold, was one of Bacon’s most loyal followers and a chief lieutenant having been involved and present at many of Bacon’s exploits. My father even told me that Anthony was present when Bacon burned the capital at Jamestown. In the aftermath of the violence of 1676, Anthony was captured and ordered to be hung by Governor Berkeley. Anthony was actually hung in our own county of King William, in West Point, from a mulberry tree which still stands today. Our family lost all of our land and what we had built up. My father and his family were orphaned, the Governor confiscated our land and home. It took my father a number of years to get our family lands back. Ben, you will do great things and strive to gain our family name back.

The above, is possibly a story that Ann Arnold Temple could have told her young son, Benjamin Temple. The events of Bacon’s Rebellion were a harbinger and presaged events leading up to the Revolution of 1776. Sometimes revolutionaries are born to be just that, sometimes they are nurtured, some are molded, and sometimes they have an inherent predisposition to become such. In 1776, 100 years after Bacon’s Rebellion, Benjamin’s moment would come and he, like Anthony Arnold, would serve in another rebellion, one that would lead to the founding of a new nation.

To better gain an understanding of Benjamin Temple, one must look at his family history to have a sense of who he was and who he was to become.

Benjamin Temple was born about 1734 in King William County, Colony of Virginia to Joseph Temple and Ann Arnold Temple. The family resided at what was once the Arnold family property, Presquile, near what was once Arnold’s Ferry. Dr. Malcolm Hart Harris has this to say about Presquile:

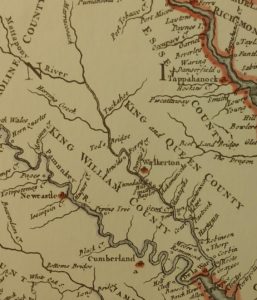

Part of the 1751 Jefferson-Fry Map of Virginia. Pictured in the center is the location of Arnold’s Ferry, later to be renamed Temple’s Ferry, in King William County.

“The Committee on Indian lands which sat at King and Queen Courthouse on January 21, 1699, had been appointed by the House of Burgesses to adjust the claims of patentees to land in Pamunkey Neck. Among the patents approved by the Committee was a patent to Benjamin Arnold for 2,000 acres of land. This patent was not recorded until 23 October 1703, probably due to conflicts when surveys were made of the land, for the tract was reduced to 1,770 acres and lay between Herring Creek and the Mattapony River lying at the mouth of Herring Creek.

This was the same tract which Benjamin Arnold had received in exchange for his plantation at Rickahock in King and Queen County when he traded land with the Chickahominie Indians.

Benjamin Arnold established his home in the bend of the river, where the Mattapony almost makes an island, hence the name. He established the ferry which bore his name, Arnold’s Ferry. In 1748 the Act of the General Assembly, which established ferries, called it Temple’s Ferry, and set the rates.”

Benjamin Temple’s father, Joseph, was born about 1699, probably in Bristol, England. Joseph came to Virginia around 1722 and married Ann Arnold, daughter of Benjamin Arnold. They would have 10 children, and astonishingly, all of them survived to make it to adulthood in a time when childhood mortality ran high due to diseases such as smallpox, whooping cough, and other maladies that carried away young ones. The children of Joseph and Ann were as follows: (1) Ann Temple, (2) Joseph Temple, (3) William Temple, (4)Benjamin Temple, our subject, (5) Sarah “Sally” Temple, (6) Hannah Temple, (7) Samuel Temple, (8) Martha Temple, (9) Molly Temple and (10) Liston Temple. Joseph settled himself and new family in King William County and set himself up as a merchant near present-day Ayletts. The family seat was Presquile, the former home site of the Arnold family.

Joseph gradually began to make a name for himself in King William County. He was a merchant in the county for a number of years. He served as an attorney for Bristol merchants who founded an iron works in Essex County, Virginia. The fact that he was an attorney, suggests that he was either a well-educated man or was well read in the law and was able to pass going to the bar. I would venture to say he was educated in England, possibly at one of the Inns of Court or some other institution as he served King William County as a justice in 1732, sheriff in 1738, and as coroner. He was sometimes referred to as Colonel, suggestive that he was probably at one time a colonel of the county militia. Over the course of his life and career in Virginia, Joseph gained moderate wealth and a sizable amount of land. At the height of his land acquisitions, he owned at least 6,000 acres of land in various locations in the colony. This land was willed to his children, and Presquile was willed to his son, Benjamin. Joseph Temple’s will was written December 20, 1744 and some records say he died shortly before 1760.

Benjamin’s mother, Ann Arnold, has colorful family history, if not exhilarating. Ann was the daughter of Benjamin Arnold and his wife, also named Ann. Benjamin Arnold’s father, Anthony, was granted land on Chickahominy Swamp on October 25, 1657 as well as lands on Blackcreek and Whorecock Creek in New Kent County. At some point after 1657, Anthony purchased Rickahock, a plot of 1,050 acres of land north of the Mattaponi River in present-day King and Queen County, from Colonel William Tayloe. Anthony was a major supporter of Nathaniel Bacon during Bacon’s Rebellion in 1676. Anthony was convicted of treason and was sentenced to be hung for his actions and support of the rebellion in New Kent County. Legend has it that he was hung from a mulberry tree in the town of West Point in present-day King William County. Anthony’s lands were confiscated by Virginia’s colonial governor, Sir William Berkeley, for his support in the rebellion. Anthony left four orphan children, including Benjamin Arnold.

In 1677, Anthony Arnold’s estate was reviewed and inventoried by commissioners sent over from England in the wake of the rebellion. Benjamin Arnold and his siblings presented a petition to the commissioners to attempt to reclaim some of their father’s lands. The Arnolds succeeded in 1688 and Benjamin was granted 1,725 acres of land at Rickahock, his father’s estate. Benjamin exchanged his lands and plantation at Rickahock in King and Queen County with the Chickahominy Indians for lands they held in King William County. It was in King William County where Benjamin Arnold established his family and home at a bend in the Mattaponi where the river almost forms an island and named the family seat Presquile. Benjamin established a ferry there that came to be called Arnold’s Ferry, later renamed Temple’s Ferry after Ann Arnold married Joseph Temple.

It was into this family that Benjamin Temple was born at Presquile in 1734. When looking at Benjamin’s life, I like to think of him as a smaller scale version of George Washington. There is not a great abundance of records of Benjamin’s life, as fires during and after the Civil War destroyed many courthouse records in the counties of King William and King and Queen. Benjamin’s early life can only be speculated. There is no record of him ever having any formal schooling. Benjamin’s parents, as many others in the time period, probably had him educated at their home or at a neighboring plantation whenever tutors were available. Outside of that education, Benjamin learned from experience.

Whatever education Benjamin received, he took up his father’s profession as a merchant having established several warehouses on the York River where he imported goods from abroad. As well as being a merchant, Benjamin served as the surveyor for King William County for a number of years. This profession would give Benjamin land acquisition opportunities. In the colonial period, one of the best ways to begin amassing land and wealth was to take up surveying. A surveyor could scope out some of the best tracts of land and make purchases for himself. They could then use the land to rent out to others for farming or the cultivation of tobacco. A case in point on this subject is George Washington, who himself had taken up surveying at a young age and used his position as a surveyor to gain land and wealth. Benjamin inherited his family lands and home at Presquile after the death of his father. He also inherited lands in Spotsylvania County that his father owned as well.

Benjamin was likely a planter like many of his time. And in the colonial period, you almost always had to be a planter; tobacco was the main currency in the colony up until the Revolution. In order to live the comfortable lifestyles that the landed gentry in Virginia lived, one had to grow tobacco, and have it sent overseas to England to be sold at market and gain credit with the merchants there who sold their Virginia tobacco. Without this system, Virginia’s elite and ruling class could not have the luxuries, houses, and goods that they acquired. But this system was a double-edged sword. Tobacco prices were constantly in a state of flux and many Virginians found themselves constantly in debt, no matter how good a crop of tobacco they had; they were always at the mercy of the merchants in the mother country. Not to mention, many upper class Virginians tended to live well above their means.

In 1754, events would lead to a new phase in young Ben Temple’s life. In that year, the French and Indian War (also known as the Seven Years War) kicked off with events greatly influenced by none other than George Washington. On May 28, 1754, a party of Virginia militia and Mingo warriors under the command of Major George Washington attacked a French diplomatic party lead by Joseph Coulon de Villiers, Comte de Jumonville at Jumonville Glen in Western Pennsylvania. Events followed that sparked the French and Indian War. Benjamin Temple became embroiled in these events in 1755 when he became an aide to Washington, who himself volunteered his services to British General Edward Braddock in his Monongahela Expedition. No records are known to exist showing that Temple served as an aide to Washington, though numerous histories state the fact. In his The Life of George Washington, Reverend Mason Locke Weems, the former rector of the Mount Vernon Parish, states that “I have often been told by colonel Ben Temple, (of King William County, Virginia,) who was one of his aids in the French and Indian war, that he has frequently known Washington, on the sabbath, read scriptures and pray with his regiment, in the absence of a chaplain; and also that, on sudden and unexpected visits into his marquee, he has, more than once, found him on his knees at his devotions.”

On July 9, 1755, the Battle of the Monongahela occurred in Braddock, Pennsylvania, near present-day Pittsburg. It is not known what role Temple played in the expedition and battle, but if he was present at the battle as an aide to Washington, he likely played some sort of role in the evacuation of British forces after General Braddock fell. Most of the British officers were wounded or killed in the battle, and Washington found himself in the unenviable position of having the command fall on his shoulders. If Benjamin Temple was present with Washington during this great British defeat, he would have gained and learned excellent leadership qualities as he saw Washington act coolly under fire.

After having served with Washington in the Braddock Expedition, Temple served as a Lieutenant in the Virginia Battalion of Regulars under the command of Colonel William Peachey in 1759, a position he held until the unit was disbanded. We know for certain that he served in the Virginia Battalion during the French and Indian War because in March of 1780, he testified in a Hanover County court that he served in the position. On November 27, 1773, a Williamsburg court order authorized the Surveyor of Augusta County to survey land that was entitled to Benjamin Temple for his service in the war:

“I do certify that Benjamin Temple is entitled to 2000 Acres of Land agreeable to his majesty’s Proclamation in the year 1763, and as he is desirous to locate the same in the County of Augusta on any of the Western Waters, if he [torn] the same on any vacant lands that have not been surveyed by order of Council and Patented since the above Proclamation. You are hereby strictly authorized and required to survey the same. Given under my hand and seal at Williamsburg the 27th day of November 1773.

To the Surveyor of

Augusta County”

What better life experience than to learn war, side by side with Washington. It is undeniable that the experience Benjamin Temple gained from his service in the French and Indian War and his association with Washington was a great steppingstone in his life and career. Combine his experiences in the war with his family history of being rebellious (and the reasons for being rebellious), then you begin to see a perfect storm begin to brew in years to come.

Family associations were a must in Colonial Virginia. Who you associated yourself with and what families you married into, could either make or break a person looking to move their way up the social ladder. Benjamin Temple associated himself well. Washington during the French and Indian War is probably the best example. He also did well in associating himself with families nearby his home base in King William County. One of the close friendships Temple made was to the Baylor family.

John Baylor I came to Virginia in the late 1600s and by 1692 had initially settled in Gloucester County. By 1704, the Baylors had amassed about 3,000 acres of land in King and Queen County and established themselves at Rickahock, formerly owned by Benjamin Arnold, Benjamin Temple’s grandfather. John Baylor I had two sons: John Baylor II and Colonel Robert Baylor.

Colonel Robert Baylor was a colonel of the King and Queen County militia. After the death of his brother, John Baylor II, he continued his brother’s business in the tobacco trade. Robert married first. He established himself at Mantua (also known as Baylors) in King and Queen County with his wife Hannah Gregory. By his first marriage he had two sons, Major Gregory Baylor and Dr. Robert Baylor. He married a second time to a woman named Frances and in this union were born two daughters, Francis and Lucy. Colonel Robert Baylor died in about 1730 at Mantua.

Doctor Robert Baylor was born at Mantua in King and Queen County. Upon the death of his father, Dr. Baylor inherited Mantua. He married Molly Brooke, daughter of Humphrey Brooke and Elizabeth Braxton of King William County. This marriage bore 1 son and 5 daughters; (1) Lieutenant John Baylor, (2) Elizabeth Baylor, (3) Molly Brooke Baylor, (4) Hannah Baylor, (5) Fanny Baylor, and (6) Mary Baylor. Humphrey Brooke was a merchant and a King William County Justice. An interesting side note: Elizabeth Braxton was the aunt of Carter Braxton, one of the Virginia signers of the Declaration of Independence. Like I said, family associations were a must for upward mobility.

What was so outstanding about the Baylor family? A number of things. They associated themselves very well with other families. They were very cultured and some of the members of the family were very well educated as the family could afford to send many of its sons to England. For example, John Baylor III was educated at Putney Grammar School and at Caius College in Cambridge, England. Members of the Baylor family had large libraries of books which again showed wealth and the level of education a gentleman had. And one other interesting fact about the Baylor family, they were horse breeders. The family was known to have the best pedigreed horses in the colony. John Baylor III purchased the famed Fearnought for an astonishing 1000 guineas (£1,050). Many of today’s racehorses can trace their ancestry back to this famed horse, for example, Big Brown, winner of the 2008 Kentucky Derby and Preakness, can trace his ancestry back to Fearnought through multiple lines.

Benjamin Temple’s connection to the Baylor family likely ran the route of business dealings and social visits to each other’s plantations; all the customary ways families in the time period interacted with one another. Whatever associations Benjamin had with the Baylor’s was further cemented in 1768 when he married Molly Brooke Baylor (born about 1748 at Mantua), daughter of Dr. Robert Baylor and Molly Brooke. As was the custom of the time, the wedding would have been held at the home of the bride. With this marriage, he most assuredly married upward which helped even further with his station in colonial society. With this union of the two families, Benjamin Temple likely gained access to the libraries of members of the Baylor family. This would have helped to further his knowledge on any subjects of interest to him or any subjects that the Baylor’s suggested he study. With the Baylor’s being known for being the best horse breeders, Temple likely also was able to acquire some of the best horses money could buy in Virginia. In turn being associated with members of the family he likely became one of the better horsemen in Virginia. This would come to aid him well in the future.

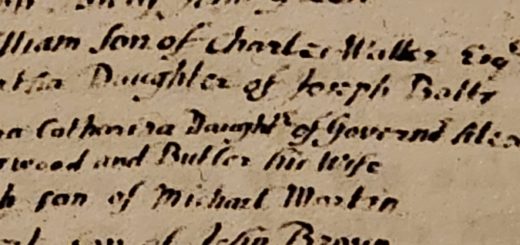

Benjamin settled his new wife at Presquile in King William County. To this union would be born 6 children: (1) Elizabeth Temple, (2) Robert Temple, (3) Reverend Benamin B. Temple, (4) Mary (Polly) Temple, (5) Ann Temple and (6) Nancy Brooke Temple. With his new family, Benjamin gained further status as he became Justice of the Peace for King William County in 1773.

Things seemed to be going fine and well with Benjamin and his growing family. But clouds were beginning to gather on the horizon. In the wake of the French and Indian War, saddled with massive debts incurred during the war, the home government across the ocean needed a way to pay those debts. To do so, the British government decided to levy new taxes on its American colonies, starting with the Stamp Act of 1765 which imposed taxes on legal papers, newspapers, pamphlets, cards, and almanacs. A highly unpopular move, Parliament quickly rescinded the Stamp Act but followed that up with the Townshend Acts which led to colonists voicing their discontent and some acts of violence broke out over these new set of taxes. In response, Parliament sent British troops to Boston to monitor the growing discontent in the colonies. Things continued to escalate when on March 5, 1770, British troops fired on a crowd in Boston, which came to be known as the Boston Massacre, killing five and wounding others. Following this event was the Boston Tea Party on the night of December 16, 1773, which led to the Intolerable Acts in 1774, a series acts including the Boston Port Act (which closed the port of Boston in response to the Tea Party) and the Quartering Act.

It is likely that Benjamin Temple was kept abreast of these events occurring in Boston and the responses to the events throughout the colonies. Knowing what his great grandfather went through in Bacon’s Rebellion such as the home government meddling in colonial affairs and the depredations placed on colonists by colonial governors (seen as representatives of the British government) this probably began to spark something in him. A feeling that things were not right and becoming tyrannical. Having a predisposition for standing up against authority, Benjamin likely took part in conversations in taverns and other meetings that helped to further cement him on the course which he would soon take. He continued to watch, listen, and wait as other events continued to unfold in the colony; the convening of the First Continental Congress, Patrick Henry’s “Give me Liberty or Give me Death” speech, the Battles of Lexington and Concord, Bunker Hill, Lord Dunmore’s removal of powder from the Magazine in Williamsburg. All these events continued to push Benjamin and others like him toward a more drastic step; all-out war and a push for independence.

While all these events were swirling around Temple, he began to take action. At some point it seems he was chosen to be a Captain of a group of minutemen in King William County as evidenced by an ad placed in the Virginia Gazette for March 8, 1776:

“At a committee held for King William County,

the 26th day of Feb. 1776.

Captain Benjamin Temple having informed this committee, that a report has been propagated much to his prejudice, respecting his conduct as to the raising of men in this county for the minute service:

Ordered, at the instance of said Temple, that it is the unanimous opinion of this committee, that he hath used every effort and endeavour in his power, as far as they know or believe, towards the promotion of said service, and are fully convinced that every such report is without a just foundation.

Ordered, that a copy of the above resolution be transmitted to the publick printer of this colony, who is requested to put the same in the Virginia Gazette.

John Watkins, clerk.”

An ad in the June 14, 1776, edition of the Virginia Gazette informs its readers that “The following gentlemen are chosen officers for the six companies of light horse directed to be raised by the Hon. General Convention, viz. Captains, Theodorick Bland, jun. Benjamin Temple, John Jameson, Lewelling Jones, Henry Lee, jun. and John Nelson, esquires.” This battalion of Virginia Dragoons was led by Bland and would eventually be incorporated into the continental army as the 1st Continental Dragoons on March 31, 1777, with Bland as its Colonel and Benjamin Temple being promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel.

On July 4, 1776, the colonies declared their independence from the British Crown. Almost immediately Captain Temple began raising recruits for his company of dragoons and took out an advertisement in the Virginia Gazette to purchase horses to equip his troops with.

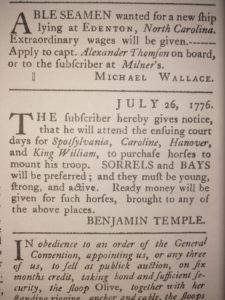

Purdie’s Virginia Gazette, July 26, 1776, pg. 3, column 3, showing Benjamin Temple’s advertisement to obtain horses. Courtesy John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library, Williamsburg, VA.

Temple’s stint with the 1st Continental Dragoons saw him experiencing some combat as well as recruiting efforts and endeavors to supply and obtain troops back pay. During the Revolution there were many times soldiers went without pay, supplies, uniforms, and food because of a lack of funds and breakdowns in the quartermaster system.

The regiment would start heading north in December 1776, but did not reach Washington’s army until after the American victories at Trenton and Princeton. They arrived for the encampment at Morristown after those victories in the Winter of 1776-77. The regiment was involved in battle at both Brandywine and Germantown in 1777 but was split up around different commands in both of those actions. The later part of 1777 saw the 1st Dragoons keeping a watch on the British who were on the New Jersey side of the Delaware River. They were also involved in foraging for supplies for the American Army and disrupting British foraging parties. For the winter, the 1st was encamped near Trenton, New Jersey.

In the campaigning of 1778, the 1st Dragoons were split up again to keep watch on the enemy. Parts of the regiment were involved in the Battle of Monmouth on June 28, 1778, but Lt. Col. Temple was away in Virginia trying to get supplies and uniforms for the regiment. A chronic problem during the war, one of the more unique aspects of Benjamin Temple’s service in the Revolution was the correspondence he had with its commander in chief, General George Washington. The correspondence between the two when Temple was back in Virginia goes to show the complexities of the supply issues that the American Army faced during the war. A letter dated March 28, 1778 from General Washington to Lt. Col. Temple details some of the issues they were confronted with:

“Head Quarters Valley Forge 28th March 1778

Sir,

I am [illegible] with yours of the 20th ult. and am glad to find that you have been able to procure most of the articles necessary for the Cloathing of the 1st Regt of Light Dragoons. Colo Bland and Colo Baylor have full powers to purchase a number of Horses, to accomplish which they are supplied with Cash and I doubt not but they will be successful. The reinlisted men and those upon furlough may be sent to Camp upon some of those Horses. Major Jameson, who was called to Virginia upon his private Business, was directed to assist Colo Bland and Baylor in the purchase of Horses. You will therefore be pleased to return and take command of the Regiment as soon as you have found a proper quantity of Cloathing.

I am sir,

Yr most obt Servt”

A letter from Lt. Col. Temple, dated August 8, 1778, to General Washington goes into more detail of the difficulties and frustrations of the supply issues the 1st Dragoons were faced with:

“[Virginia] August 8th 1778.

sir

I am exceedly unhappy to find in your’s to Colo. Bland of July 22d, after all the pains and fatigue I have taken to be censured about the clothing of the Regt; I do not know what Colo. Bland has inform’d your Excelly nor do I know what is meant, by the greatest part of the clothing, I have engaged should have been apply’d for other purposes, by Mr Finne, he only made use of one hundred & thirty four Shirts, after I had given him a receipt for them, I can with truth, assure yr Excelly that altho I lost many articles, that I had engaged, when I first came in, for the want of money, I have long since compleated that business, with a sufficient quantity of every article to compleatly cloath every man, in the Regt except Boots, they may want a few pair, which I inform’d your Excelly were not be had, and I doubt not but they will be as well equipt as Colo. Moylands, or Colo. Sheldens Regts, and might been at Camp two months ago, if I had not received orders from Colo. Mead and Colo. Bland to remain in Virga to assist him in purchasing accoutrements, which was by no means agreeable, as the Tradsmen expect ready money, for every thing they do, and I have not yet been furnish’d with money to comply with my engagments for the clothing, and not one shilling till the month of June, I got Ten thousand Dollars of Mr Finne, I have engaged Sixty setts of accoutrements, which will be compleat in ten days, and have promised the tradsmen, they shall have the money as soon as the work is finished, On application to Colo. Bland, who promised to pay the money when done, he informs me he is quite out, and has sent me an order on Colo. Baylor which he refuses to pay, in this disagreeable situation have I been ever since I have been in Virga the inclos’d letter will show that my long stay in Virga was by no means my wish, and that I have not been imploy’d solly in procuring clothing, I am with great respect Yr Excelly Mo. Obt Hhble Servt

Benja. Temple”

After the Battle at Monmouth, the 1st Dragoons were done with campaigning for the rest of the year and were quartered in Winchester, Virginia for the winter. The regiments sojourn in Winchester must have been a pleasant respite from the harsh winter camps of Pennsylvania, as it seems the citizens of the town were very glad to have Continental troops bivouacked in their vicinity and paid a great thanks to Temple and his troops.

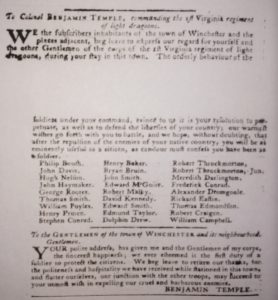

Dixon and Hunter’s Virginia Gazette, June 5, 1779. Courtesy John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library, Williamsburg, VA.

1779 was a year of change for the 1st Dragoons and for Benjamin Temple. The month of March saw them short of men in their ranks as they were only able to field about 80 troops. Around this same time, they received orders to head south to join up with the Southern Army under the command of Benjamin Lincoln in South Carolina. After delays due to equipment issues, they were able to finally travel south to join up with Lincoln’s army. Lt. Col. Temple was given command of the 1st Dragoons as Colonel Bland was detailed to stay up north to be placed in charge of British prisoners from the American victory at Saratoga. On October 9, the 1st Dragoons were part of the failed attack on Savannah, Georgia. Afterward, they were detached with some Virginia infantry to Augusta, Georgia where they remained the rest of the year.

A big change occurred near the end of the year for Benjamin. On December 10, 1779, he was transferred to the 4th Continental Light Dragoons to replace another officer who had received a promotion. The 4th Dragoons were commanded by Colonel Stephen Moylan of Philadelphia. He began forming the 4th in January of 1777. It was around the time of Temple’s transfer that Colonel Moylan was employing his officers and troopers in New York City as spies to gather information on British General Henry Clinton’s forces. How exhilarating and yet nerve wracking it must have been for Lt. Col. Temple if he was at all involved in the espionage activity in New York. General Washington was using a very effective spy network in New York which provided him with valuable information to make moves when and as needed, and it is likely that some men of the 4th Dragoons were used at times in this network.

The most significant event that the 4th Dragoons were involved in occurred in 1780 with troops under the command of General “Mad” Anthony Wayne in his July 20th attack on a blockhouse at Bull’s Ferry near Fort Lee on the Hudson River in New York. Wayne’s troops made a diversionary attack while the 4th Dragoons swept in and escaped with much needed supplies, fresh mounts for the men, and cattle for Washington’s Army. In December, the 4th encamped for the winter in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

The decisive year in the Revolution was 1781. Events began to unfold that would lead to the securing of American Independence. In the south, Nathaniel Greene was standing toe to toe with General Charles Cornwallis. In the north, Washington was planning with the French, getting information as it unfolded in the south, and was formulating a campaign that would bring the ultimate victory he had been seeking since he took command of the American Army in 1775. That masterstroke was looking like it was going to occur in Virginia, as the bulk of the 4th Dragoons was led south by Lt. Col. Temple to join up with Lafayette in Virginia. The rest of the 4th travelled to Virginia with Washington and the main army. A combined complement of American and French forces cornered General Cornwallis at Yorktown in September 1781. The 4th Dragoons were given a position of honor on the right flank of the American lines during the siege. The British surrender on October 19 was the beginning of the end of the Revolution. After the British surrender at Yorktown, the 4th Dragoons were sent to the southern department in January 1782 where they served out the rest of the war until the regiment was disbanded on June 11, 1783, in Philadelphia. The war was concluded with the signing of the Treaty of Paris on September 3, 1783. We were officially a new nation, and men such as Benjamin Temple served to make that new nation a reality. But the work of nation building was not over, it had just begun. What would be the new form of government? Who would head it? Where would it be located? All these questions would be decided by our founders and many who had taken leading roles in fighting for our independence.

In May 1783, General Henry Knox, Washington’s renowned artillery commander during the Revolution, started a fraternal organization for officers who served the Patriot cause, the Society of the Cincinnati. Washington himself was once a President General of the society. Benjamin Temple was one of the many officers who became members of this famed organization.

With the conclusion of the Revolution, Benjamin Temple returned to his home in King William County. But his respite at home was short lived as he was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates in 1784 for King William County, a seat he held until 1789. As a delegate, he served on a few committees during his time in office; Committee of Privileges and Elections, Committee of Commerce and Committee of Propositions and Grievances.

By far, Benjamin Temple’s greatest contribution as a politician was serving as a delegate for Virginia’s Constitutional Convention in 1788. After having just fought a war to sling off the chains of a tyrannical government, Temple and many others in the Virginia Convention were leery of the new Constitution that had been adopted by several the new states. Their fears probably centered around a central government with too much power which they viewed as a danger to personal liberties and could bring about the same tyranny that they had all sought to escape. Benjamin served as the delegate to Virginia’s Constitutional Convention for King William County, alongside fellow Revolutionary War veteran Holt Richeson. The Convention met, debated, and deliberated in Richmond, Virginia at the Richmond Theater from June 2 through June 27. The stakes were high in the ensuing debates over whether to ratify the Constitution. There were some in Virginia who wanted to hurry to vote for ratification so Virginia could be the ninth and deciding vote for nationwide ratification. The final vote was close; 89 for ratification, 79 against.

Ben Temple and Holt Richeson both voted against ratifying the Constitution. Why? Both having been former Revolutionary War officers and having seen the depredations of a strong government such as Great Britain, the two probably were against having a strong central government as formed by the Constitution. It was a struggle for Federalists in Virginia to get ratification through, having taken much lobbying on the part of Washington, James Madison, and Edmund Randolph. Though he was against the Federalists in the beginning, Temple would become a Federalist himself as he was elected to the Virginia State Senate in 1790 on the Federalist ticket and served in that capacity until 1799. In 1799, Temple ran for a seat in the United States Congress for Virginia’s 16th District but was soundly defeated by Anthony New. In 1800, Temple again ran to regain his seat as a state senator but was beaten by Thomas Roane, Jr. Thus ended his political career.

To gain a better idea of who Temple was as a person, looking at his voting on bills as a member of Virginia’s House of Delegates opens a window into what he believed in. For one, as already mentioned, he was for smaller government having voted against ratifying the Constitution. When it came to religion, he was for religious freedom evidenced by his yes vote on a bill for religious freedom on December 17, 1785. As many Southern planters, gentry, and politicians of his time, he without a doubt owned slaves having been a businessman and a planter himself. I am not making excuses for Temple, but he was a man of his times. Slavery was a great tarnish on our nation’s history, it was an institution that should have been snuffed out by men such as Temple, Washington, Jefferson and others. Unfortunately, it was not. Had our founders done more to end slavery, then they would have given more validity to the views and beliefs they espoused in the Declaration of Independence. It is regretful that Temple voted against bills to provide for the manumission of slaves in Virginia. It is especially disappointing that former soldiers and officers of the Revolution did not support freedom for slaves considering the bravery and gallantry of some people of color who also served to make independence a reality.

On February 8, 1802, Benjamin Temple was granted 200 acres of land in Ohio for his services in the Revolution by President Thomas Jefferson. It is unknown what became of this land but according to the grant, the land would go to his heirs. Benjamin Temple made his will in 1800. He died in 1802 as the will was proved in King William County Court on September 27, 1802. His wife, Molly Brooke Baylor survived him by 18 years, dying on August 20, 1820 at the age of 72. The locations of their burials are unknown, but it is likely that they were probably buried in King William County.

References

Bruce, Philip Alexander. Virginia: Rebirth of the Old Dominion. Chicago and New York: The Lewis Publishing Company, 1929.

“From George Washington to Lieutenant Colonel Benjamin Temple, 28 March 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-14-02-0316. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 14, 1 March 1778-30 April 1778, ed. David R. Hoth. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2004, p. 344.]

Grigsby, Hugh Blair. The History of the Virginia Federal Convention of 1788, With Some Account of the Eminent Virginians of That Era Who Were Members of the Body, Vol. I. Richmond, Virginia: Virginia Historical Society, 1890.

Grigsby, Hugh Blair. The History of the Virginia Federal Convention of 1788, With Some Account of the Eminent Virginians of That Era Who Were Members of the Body, Vol. II. Richmond, Virginia: Virginia Historical Society, 1891.

Harris, Malcolm Hart. Old New Kent County: Some Account of the Planters, Plantations, and Places in New Kent County, 2 vols. West Point, Virginia: Malcolm Hart Harris, 1977.

Hunter, William and Alexander Purdie. Virginia Gazette, June 5, 1779, pg. 3, column 1 and 2.

Katheder, Thomas. The Baylors of Newmarket: The Decline and Fall of a Virginia Planter Family. New York: iUniverse Inc., 2009.

Loescher, Burt Garfield. Washington’s Eyes: The Continental Light Dragoons. Fort Collins, Colorado: The Old Army Press, 1977.

Long, Todd Eberle. Voices of the Past: The Long and Brooks Family History. Fullerton, California: Creative Continuum, 2013.

Pollard, William. “French & Indian War Service of Benjamin Temple.” Hanover County Historical Society Bulletin 41 (November 1989): 7.

Purdie, Alexander. Virginia Gazette, March 8, 1776 (supplement), pg. 2, column 2.

Purdie, Alexander. Virginia Gazette, June 14, 1776, pg. 2, column 2.

Purdie, Alexander. Virginia Gazette, July 26, 1776, pg. 3, column 3.

Temple, Levi Daniel. Some Temple Pedigrees: A Genealogy of the Known Descendants of Abraham Temple, Who Settled in Salem, Massachusetts, In 1636. Boston: David Clapp & Son, 1900.

“To George Washington from Lieutenant Colonel Benjamin Temple, 8 August 1778,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-16-02-0289. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 16, 1 July-14 September 1778, ed. David R. Hoth. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2006, pp. 277-278.]

Weems, Mason Locke. The Life of George Washington: With Curious Anecdotes, Equally Honorable to Himself and Exemplary to His Young Countrymen. Philadelphia: M.L. Weems, 1810.

Really interesting and informative

Glad you enjoyed it.

Great article!

Very interesting biographical information on Benjamin Temple. My son is moving to a city in Ohio called Washington Court House on Temple Street. I’m wondering if this is the Ohio land you referenced that was given to Benjamin Temple?

This could well be the case!!!

Thank you so much for doing the research on Benjamin Temple. His son, Benjamin Burnley Temple was the enslaver of my great-great grandfather. I have always wanted to read the Wills of both men so that I could possible see my gg-grandfather’s journey. I recognized the names throughout this article and have been very interested over the years. If you think you may have seen any enslaved people’s names in your research ,please let me know. Thanks again for this article.

Hello Todd: Getting ready to read the article. I am the cousin of Cecilia Boler. I am particularly interested in how families migrated and why. It would be interesting to find out if those enslaved were taken or sold to parties and moved out of the area. Thank you for sharing

Do you have pictures of Temple and his family?

Unfortunately, no. At least not of Benjamin the Rev War soldier. There are a couple of pictures out there of some of his great grandchildren.

I am also a descendent of Benjamin Temple. Thank you for this article! Fascinating and informative.

Glad you enjoyed the article Lori.