David Kendlehart: A Gettysburg Civilian’s Account, July 6, 1863

“and evry [sic] Loyal person was engaged assisting in some way I was at Hoke’s warehouse when news came that our men where [sic] falling back I hurried down but coudent [sic] get my shoes to the place they where [sic] before so in the hurry without we carried them up and put them in my shop as the safest place never thinking they would look there”—David Kendlehart, July 6, 1863

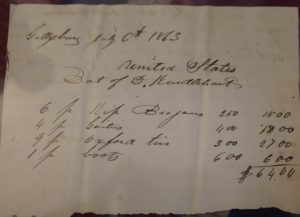

Reverse side of the document produced by David Kendlehart.

This is an account of David Kendlehart, president of the Gettysburg town council, from a partial document written by Kendlehart to the United States government, likely seeking recompense for the loss of merchandise from his store.

David Kendlehart. Photograph courtesy of the Frederick News-Post.

Born December 13, 1813 in Gettysburg, David Kendlehart was a prominent citizen of the town. His parents John and Elizabeth (Flentgen) Kendlehart were from Germany, making him a first generation United States citizen. Early on in his life, David was apprenticed in the shoemaker trade, a career likely imparted to him as his father was a shoemaker. By the time of 1863, Kendlehart had become a wealthy man in Gettysburg, owning and operating a shoe store on Baltimore Street. As well as being a wealthy merchant, he served as the director of the Bank of Gettysburg from 1852 until his death in 1891. He was also engaged in politics. In early 1863, he became the president of the Gettysburg Town Council after the medical resignation of Councilman William McClellan. In the midst of local politics, storm clouds were brewing on the horizon.

In June of 1863, fresh off his miraculous and stunning victory at the Battle of Chancellorsville, Confederate General Robert E. Lee began moving his army north on his second invasion of the Union in hopes of bringing the war to a conclusion, winning independence for the South. He moved his scattered army north through the mountains of Virginia, up through Maryland and into Pennsylvania. As his army moved north, various alerts and warnings were going throughout the state of Pennsylvania informing local towns and boroughs of the advent of Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia.

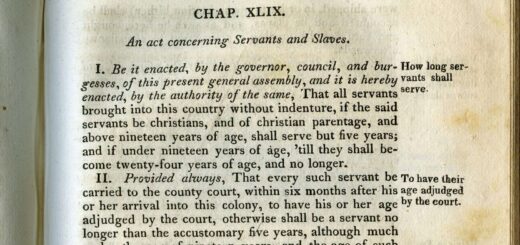

On June 26, 1863, the division of General Jubal Early entered Gettysburg. Many members of the town council and the Mayor of Gettysburg, Robert Martin, had already fled the town on hearing of the approach of Lee’s army. One of the few fathers of the town who did not flee and neglect his duty was David Kendlehart. Being the ranking politician in the town, Kendlehart assumed the responsibility of negotiating with Early when his demands were made. In his talks with Kendlehart, Early demanded large amounts of provisions, 1,000 pairs of shoes, 500 hats, or $10,000 in cash. Kendlehart refused the demands saying that the borough could not meet the requests but did offer to open all businesses and shops encouraging the townspeople to offer up what they could to Early and his men.

“Gettysburg

June 26/63

General Erley,

Sir The authorities of the borough of Gettysburg in answer to the demands made by you upon the said Borough and County, say their authority extends but to the Borough, that the requisitions asked for cannot be given, because it is utterly impossible to so comply – The quantities required are far beyond that in our possession. In compliance however to the demands, we will require the stores to be opened, and all the citizens to furnish whatever they can of such provisions etc, as may be asked—further we cannot promise. By authority of the Council of the Borough of Gettysburg, I herewith as President of said Board, attach my name. Kendlehart”

Ultimately not much was requisitioned by Early’s troops, as many citizens hid much of their stores and supplies. That evening, Kendlehart left the town and went to McAllister’s Mill just a couple of miles outside of town for the duration of what would come to pass at Gettysburg.

Hundreds, thousands of accounts exist that speak of events that occurred during and after the battle at Gettysburg. Much less exists noting the events in Gettysburg that led up to the battle. The document written by Kendlehart offers a glimpse into the efforts of Gettysburg and its civilians to conceal and stow away important materials that could have very much aided the Army of Northern Virginia. In his account, Kendlehart notes that many of the citizens were helping him, as they did with others, to shift around and hide supplies from the marauding invaders. His efforts to hide his shoes and boots were not entirely successful. On the reverse of the document, Kendlehart lists items he is seeking to get compensation for: 6 pairs of brogans (shoes) valued at $2.50/pair, 4 pairs of gaiters at $4.00/pair, 9 pairs of oxford ties at $3.00/pair and 1 pair of boots valued at $6.00/pair coming out to a total of $64.00 in lost merchandise. This accounting of merchandise lost, is one of the few records that shows items taken by Confederates leading up to the Battle of Gettysburg. It also provides an interesting account on the civilian side of what led up to the vicious battle that occurred July 1-3, 1863.

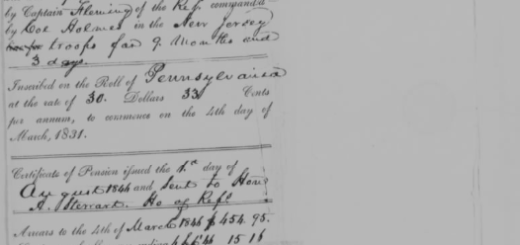

Obverse of the Kendlehart document.

One interesting discussion that has been had many times is, what led the Confederates to Gettysburg? Was it the roads, shoes, supplies, the ground to fight upon? This first-hand account lends credence to the idea that the Battle of Gettysburg occurred because Confederate troops were there looking for shoes and supplies. Gettysburg was a commercial hub that could easily supply an army with much needed materiel to further conduct the war. But, on the other hand, many roads did lead to this locale, so one could make the argument that it was both the roads and that it could be a supply center that led the two armies to meet at Gettysburg. Whatever the conclusion, one fact cannot be denied; Gettysburg was one of the most pivotal and bloody battles fought in the Civil War.

On July 4, 1863, Kendlehart entered Union lines to inform the commander of the Army of the Potomac, Major General George Gordon Meade, that the Confederates had withdrawn from the town. Two days later, he wrote his account of what occurred and petitioned the government for compensation for the loss of his merchandise; it is unknown if he ever received such restitution. After the conclusion of the battle, Kendlehart continued as one of Gettysburg’s more prominent citizens. He died April 30, 1891, and is buried at the famed Evergreen Cemetery in Gettysburg.

References

Civilians at Gettysburg. National Park Service, accessed 4 June 2021. https://www.nps.gov/gett/learn/historyculture/civilians-at-gettysburg.htm.

Coddington, Edwin B. The Gettysburg Campaign: A Study in Command. New York, NY: Touchstone, 1997.

CW/VFM-50: Kendlehart, Gettysburg College, Musselman Library Special Collections, accessed 4 June 2021. https://www.gettysburg.edu/special-collections/pdfs/cwvfm/CWVFM-050.pdf.

Ross, Jacob. To Preserve, Protect, and Defend, The Gettysburg Compiler: On The Front Lines of History, accessed 4 June 2021. https://gettysburgcompiler.org/2014/10/15/to-preserve-protect-and-defend/.

Very interesting! Enjoyed reading this.

Glad you enjoyed it!!!

Good information my friend

Thanks buddy, glad you enjoyed it.

Great article. David Kendlehart was my Great Great Great Grandfather.

Scott, what an awesome family connection to have. So how does it feel and what does it mean to you to have such a BIG connection to Gettysburg and the epic battle fought there?

Todd