Establishing a Slave Society: Virginia and the 1705 Slave Codes, Part 2

An act concerning servants and slaves: Virginia’s Slave Codes of 1705

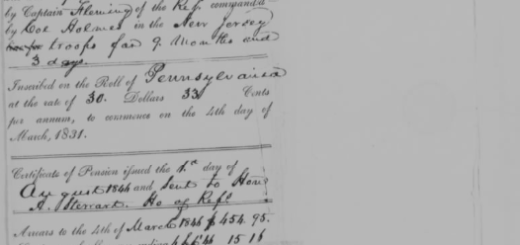

With the establishing of Virginia as a slave society through laws that eliminated enslaved peoples rights, colonial officials next sought to condense these laws spread out across the 17th century, into one comprehensive set of laws that would govern the enslaved chattel of Colonial Virginia’s elite and prominent men. These laws have come to be known as the 1705 Slave Codes. Many other laws would follow the 1705 Slave Codes, but these laws became the basis for all future laws governing slavery that would be passed in Virginia. The laws would also become the basis for other colonies and future states as they adopted laws regarding the enslaved. All of the laws of the 1705 Slave Codes were not solely aimed at the enslaved. Some of the laws also dealt with indentured servants, but further widened the divide between those who were enslaved and those who were not. This also created another class, allowing servants to hold a place above that of those who were enslaved. So buckle up, there were forty-one laws passed by the House of Burgesses in October, 1705!!!

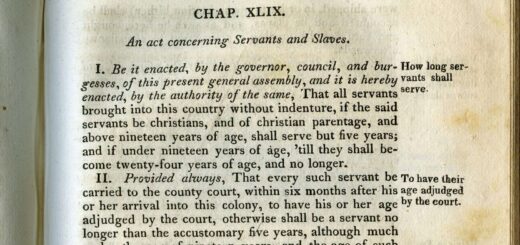

CHAP. XLIX.

An act concerning Servants and Slaves.

I. Be it enacted, by the governor, council, and burgesses, of this present general assembly, and it is hereby enacted, by the authority of the same, That all servants brought into this country without indenture, if the said servants be christians, and of christian parentage, and above nineteen years of age, shall serve but five years; and if under nineteen years of age, ‘till they shall become twenty-four years of age, and no longer.

II. Provided always, That every such servant be carried to the county court, within six months after his or her arrival into this colony, to have his or her age adjudged by the court, otherwise shall be a servant no longer than the accustomary five years, although much under the age of nineteen years; and the age of such servant being adjudged by the court, within the limitation aforesaid, shall be entered upon the records of the said court, and be accounted, deemed, and taken, for the true age of the said servant, in relation to the time of service aforesaid.

III. And also be it enacted, by the authority aforesaid, and it is hereby enacted, That when any servant sold for the custom, shall pretend to have indentures, the master or owner of such servant, for discovery of the truth thereof, may bring the said servant before a justice of the peace; and if the said servant cannot produce the indenture then, but shall still pretend to have one, the said justice shall assign two months time for the doing thereof; in which time, if the said servant shall not produce his or her indenture, it shall be taken for granted that there never was one, and shall be a bar to his or her claim of making use of one afterwards, or taking any advantage by one.

IV. And also be it enacted, by the authority aforesaid, and it is hereby enacted, That all servants imported and brought into this country, by sea or land, who were not christians in their native country, (except Turks and Moors in amity with her majesty, and others that can make due proof of their being free in England, or any other christian country, before they were shipped, in order to transportation hither) shall be accounted and be slaves, and as such be here bought and sold notwithstanding a conversion to christianity afterwards.

The 4th law in this act served to reenforce the 1667 act “declaring that baptisme of slaves doth not exempt them from bondage.” As in the earlier discussed case of Elizabeth Key, enslaved persons were able to gain their freedom if they were Christian or converted to Christianity. It was likely her case, and others like it, that prompted the passing of the 1667 law and it’s being reissued in 1705. Both the 1667 and 1705 acts in regards to enslaved Christians flew in the face of English Common Law which believed that Christians should not enslave other Christians. But an exception was made in Virginia because the slave trade proved extremely profitable to England in what it produced in the Caribbean and the American colonies in the form of tobacco, sugar, rice, indigo, and other such commodities.

V. And be it enacted, by the authority aforesaid, and it is hereby enacted, That if any person or persons shall hereafter import into this colony, and here sell as a slave, any person or persons that shall have been a freeman in any christian country, island, or plantation, such importer and seller as aforesaid, shall forfeit and pay, to the party from whom the said freeman shall recover his freedom, double the sum for which the said freeman was sold. To be recovered, in any court of record within this colony, according to the course of the common law, wherein the defendant shall not be admitted to plead in bar, any act or statute for limitation of actions.

Under this law, and the instances were rare, Black people who were brought to Virginia and enslaved and later proved to be a victim of illegal importation into the colony, having been free where they previously lived, could regain their freedom. But providing proof of such was difficult. Unless they could prove their free status or provide manumission papers, they could be forced into slavery. A good example of this is the Supreme Court Case, United States v. The Amistad. The Supreme Court ultimately ruled that they were illegally obtained and were free.

VI. Provided always, That a slave’s being in England, shall not be sufficient to discharge him of his slavery, without other proof of his being manumitted there.

England was long considered a place of “free soil”, and a 17th century account stated that if slaves came to England, they became as free as their masters. No legislation existed for slaves and bondmen in England and slavery was not legal. Despite this, as previously mentioned, Virginia law was able to supersede English law and custom in matters that proved beneficial to the Mother Country. This law closed the door to one of the few remaining avenues to freedom for enslaved Africans and Black persons.

VII. And also be it enacted, by the authority aforesaid, and it is hereby enacted, That all masters and owners of servants, shall find and provide for their servants, wholesome and competent diet, clothing, and lodging, by the discretion of the county court; and shall not, at any time, give immoderate correction; neither shall, at any time, whip a christian white servant naked, without an order from a justice of the peace; And if any, notwithstanding this act, shall presume to whip a christian white servant naked, without such order, the person so offending, shall forfeit and pay for the same, forty shillings sterling, to the party injured: To be recovered, with costs, upon petition, without the formal process of an action, as in and by this act is provided for servants complaints to be heard; provided complaint be made within six months after such whipping.

VIII. And also be it enacted, by the authority aforesaid, and it is hereby enacted, That all servants, (not being slaves,) whether imported, or become servants of their own accord here, or bound by any court or church-wardens, shall have their complaints received by a justice of the peace, who, if he find cause, shall bind the master over to answer the complaint at court, and it shall be there determined: And all complaints of servants, shall and may, by virtue hereof, be received at any time, upon petition, in the court of the county wherein they reside, without the formal process of an action; and also full power and authority is hereby given to the said court, by their discretion, (having first summoned the masters or owners to justify themselves, if they think fit,) to adjudge, order, and appoint what shall be necessary, as to diet, lodging, clothing, and correction: And if any master or owner shall not thereupon comply with the said court’s order, the said court is hereby authorised and impowered, upon a second just complaint, to order such servant to be immediately sold at an outcry, by the sheriff, and after charges deducted, the remainder of what the said servant shall be sold for, to be paid and satisfied to such owner.

IX. Provided always, and be it enacted, That if such servant be so sick or lame, or otherwise rendered so uncapable, that he or she cannot be sold for such a value, at least, as shall satisfy the fees, and other incident charges accrued, the said court shall then order the church-wardens of the parish to take care of and provide for the said servant, until such servant’s time, due by law to the said master, or owner, shall be expired, or until such servant, shall be so recovered, as to be sold for defraying the said fees and charges: And further, the said court, from time to time, shall order the charges of keeping the said servant, to be levied upon the goods and chattels of the master or owner of the said servant, by distress.

X. And be it also enacted, That all servants, whether, by importation, indenture, or hire here, as well feme coverts, as others, shall, in like manner, as is provided, upon complaints of misusage, have their petitions received in court, for their wages and freedom, without the formal process of an action; and proceedings, and judgment, shall, in like manner, also, be had thereupon.

XI. And for a further christian care and usage of all christian servants, Be it also enacted, by the authority aforesaid, and it is hereby enacted, That no negros, mulattos, or Indians, although christians, or Jew, Moors, Mahometans, or other infidels, shall, at any time, purchase any christian servant, nor any other, except of their own complexion, or such as are declared slaves by this act: And if any negro, mulatto, or Indian, Jew, Moor, Mahometan, or other infidel, or such as are declared slaves by this act, shall, notwithstanding, purchase any christian white servant, the said servant shall, ipso facto, become free and acquit from any service then due, and shall be so held, deemed, and taken: And if any person, having such christian servant, shall intermarry with any such negro, mulatto, or Indian, Jew, Moor, Mahometan, or other infidel, every christian white servant of every such person so intermarrying, shall, ipso facto, become free and acquit from any service then due to such master or mistress so intermarrying, as aforesaid.

This law smacks of racism to all who are non-white Christians. In Colonial Virginia, if you were Black, Native, Jewish, Moorish, or Mahometan (Muslim or Islamic), then you could not own a servant who was a white Christian. If you were one of these minority groups and you did have a white servant, that servant would be freed. These groups could only have servants, or slaves, who were not white. This law strengthened a previous law passed in 1676.

XII. And also be it enacted, by the authority aforesaid, and it is hereby enacted, That no master or owner of any servant shall during the time of such servant’s servitude, make any bargain with his or her said servant for further service, or other matter or thing relating to liberty, or personal profit, unless the same be made in the presence, and with the approbation, of the court of that county where the master or owner resides: And if any servants shall, at any time bring in goods or money, or during the time of their service, by gift, or any other lawful ways or means, come to have any goods or money, they shall enjoy the propriety thereof, and have the sole use and benefit thereof to themselves. And if any servant shall happen to fall sick or lame, during the time of service, so that he or she becomes of little or no use to his or her master or owner, but rather a charge, the said master or owner shall not put away the said servant, but shall maintain him or her, during the whole time he or she was before obliged to serve, by indenture, custom, or order of court: And if any master or owner, shall put away any such sick or lame servant, upon pretence of freedom, and that servant shall become chargeable to the parish, the said master or owner shall forfeit and pay ten pounds current money of Virginia, to the church-wardens of the parish where such offence shall be committed, for the use of the said parish: To be recovered by action of debt, in any court of record in this her majesty’s colony and dominion, in which no essoin, protection, or wager of law, shall be allowed.

XIII. And whereas there has been a good and laudable custom of allowing servants corn and cloaths for their present support, upon their freedom; but nothing in that nature ever made certain, Be it also enacted, by the authority aforesaid, and it is hereby enacted, That there shall be paid and allowed to every imported servant, not having yearly wages, at the time of service ended, by the master or owner of such servant, viz: To every male servant, ten bushels of indian corn, thirty shillings in money, or the value thereof, in goods, and one well fixed musket or fuzee, of the value of twenty shillings, at least: and to every woman servant, fifteen bushels of indian corn, and forty shillings in money, or the value thereof, in goods: Which, upon refusal, shall be ordered, with costs, upon petition to the county court, in manner as is herein before directed, for servants complaints to be heard.

XIV. And also be it enacted, by the authority aforesaid, and it is hereby enacted, That all servants shall faithfully and obediently, all the whole time of their service, do all their masters or owners just and lawful commands. And if any servant shall resist the master, or mistress, or overseer, or offer violence to any of them, the said servant shall, for every such offence, be adjudged to serve his or her said master or owner, one whole year after the time, by indenture, custom, or former order of court, shall be expired.

The punishment for servants who resist their masters, as discussed in Law XIV, is not as severe as that for those who were enslaved. Enslaved people who resisted their white enslavers or threatened them with violence could be killed for such offences.

XV. And also be it enacted, by the authority aforesaid, and it is hereby enacted, That no person whatsoever shall buy, sell, or receive of, to, or from, any servant, or slave, any coin or commodity whatsoever, without the leave, license, or consent of the master or owner of the said servant, or slave: And if any person shall, contrary hereunto, without the leave or license aforesaid, deal with any servant, or slave, he or she so offending, shall be imprisoned one calendar month, without bail or main-prize; and then, also continue in prison, until he or she shall find good security, in the sum of ten pounds current money of Virginia, for the good behaviour for one year following; wherein, a second offence shall be a breach of the bond; and moreover shall forfeit and pay four times the value of the things so bought, sold, or received, to the master or owner of such servant, or slave: To be recovered, with costs, by action upon the case, in any court of record in this her majesty’s colony and dominion, wherein no essoin, protection, or wager of law, or other than one imparlance, shall be allowed.

Act 15 deals with people who wanted to trade with servants and enslaved people, which they needed the permission of the owner to do so, otherwise there would be a penalty against the offender. The intent of this act was to keep the enslaved in total dependence of their enslavers, by way of preventing them from having any economic autonomy and limiting the ability to trade with others.

XVI. Provided always, and be it enacted, That when any person or persons convict for dealing with a servant, or slave, contrary to this act, shall not immediately give good and sufficient security for his or her good behaviour, as aforesaid: then, in such case, the court shall order thirty-nine lashes, well laid on, upon the bare back of such offender, at the common whipping-post of the county, and the said offender to be thence discharged of giving such bond and security.

XVII. And also be it enacted, by the authority aforesaid, and it is hereby enacted, and declared, That in all cases of penal laws, whereby persons free are punishable by fine, servants shall be punished by whipping, after the rate of twenty lashes for every five hundred pounds of tobacco, or fifty shillings current money, unless the servant so culpable, can and will procure some person or persons to pay the fine; in which case, the said servant shall be adjudged to serve such benefactor, after the time by indenture, custom, or order of court, to his or her then present master or owner, shall be expired, after the rate of one month and a half for every hundred pounds of tobacco; any thing in this act contained, to the contrary, in any-wise, notwithstanding.

XVIII. And if any women servant shall be delivered of a bastard child within the time of her service aforesaid, Be it enacted, by the authority aforesaid, and it is hereby enacted, That in recompence of the loss and trouble occasioned her master or mistress thereby, she shall for every such offence, serve her said master or owner one whole year after her time by indenture, custom, and former order of court, shall be expired; or pay her said master or owner, one thousand pounds of tobacco; and the reputed father, if free, shall give security to the church-wardens of the parish where that child shall be, to maintain the child, and keep the parish indemnified; or be compelled thereto by order of the county court, upon the said church-wardens complaint: But if a servant, he shall make satisfaction to the parish, for keeping the said child, after his time by indenture, custom, or order of court, to his then present master or owner, shall be expired; or be compelled thereto, by order of the county court, upon complaint of the church-wardens of the said parish, for the time being. And if any woman servant shall be got with child by her master, neither the said master, nor his executors administrators, nor assigns, shall have any claim of service against her, for or by reason of such child; but she shall, when her time due to her said master, by indenture, custom or order of court, shall be expired, be sold by the church-wardens, for the time being, of the parish wherein such child shall be born, for one year, or pay one thousand pounds of tobacco; and the said one thousand pounds of tobacco, or whatever she shall be sold for, shall be sold for, shall be emploied, by the vestry, to the use of the said parish. And if any woman servant shall have a bastard child by a negro, or mulatto, over and above the years service due to her master or owner, she shall immediately, upon the expiration of her time to her then present master or owner, pay down to the church-wardens of the parish wherein such child shall be born, for the use of the said parish, fifteen pounds current money of Virginia, or be by them sold for five years, to the use aforesaid: And if a free christian white woman shall have such bastard child, by a negro, or mulatto, for every such offence, she shall, within one month after her delivery of such bastard child, pay to the church-wardens for the time being, of the parish wherein such child shall be born, for the use of the said parish fifteen pounds current money of Virginia, or be by them sold for five years to the use aforesaid: And in both the said cases, the church-wardens shall bind the said child to be a servant, until it shall be of thirty one years of age.

Act 18 reinforces parts of the 1691 act for “suppressing outlying Slaves”. The conditions of the penalties for having bastard children between white people and Black people are the same except that the child born would now be bound out by the parish for thirty-one years instead of the thirty years stipulated in the 1691 act. This act was put in place to attempt to discourage the intermixing of the races, and the children of such unions were to be used as pawns to effect this.

XIX. And for a further prevention of that abominable mixture and spurious issue, which hereafter may increase in this her majesty’s colony and dominon, as well by English, and other white men and women intermarrying with negros or mulattos, as by their unlawful coition with them, Be it enacted, by the authority aforesaid, and it is hereby enacted, That whatsoever English, or other white man or woman, being free, shall intermarry with a negro or mulatto man or woman, bond or free, shall, by judgment of the county court, be committed to prison, and there remain, during the space of six months, without bail or mainprize; and shall forfeit and pay ten pounds current money of Virginia, to the use of the parish, as aforesaid.

Act 19 of the 1705 Slave Codes strengthened the previous provisions of the 1691 act. The 1691 act for “suppressing outlying Slaves” banned interracial marriage and in any case that such union occurred, the couple were to be banned from the colony within three months. Under this new act, the white person involved in an interracial marriage was to be jailed for six months, without bail or mainprize. Mainprize was the act of releasing a prisoner from custody upon the security of sureties, known as “mainpernors”, who guaranteed the prisoner’s appearance in court at a specific time and place. This was yet another attempt to restrict the intermixing of the races.

XX. And be it further enacted, That no minister of the church of England, or other minister, or person whatsoever, within this colony and dominion, shall hereafter wittingly presume to marry a white man with a negro or mulatto woman; or to marry a white woman with a negro or mulatto man, upon pain of forfeiting and paying, for every such marriage the sum of ten thousand pounds of tobacco; one half to our sovereign lady the Queen, her heirs and successors, for and towards the support of the government, and the contingent charges thereof; and the other half to the informer: To be recovered, with costs, by action of debt, bill, plaint, or information, in any court of record within this her majesty’s colony and dominion, wherein no essoin, protection, or wager of law, shall be allowed.

In an effort to further restrict interracial marriage, Virginia’s House of Burgesses passed Act 20, adding a new stipulation that would penalize any member of the clergy who would officiate the marriage of an interracial couple. And the penalty was not a small one, but ten thousand pounds of tobacco, more than half of their yearly salary of sixteen thousand pounds of tobacco in 1705.

XXI. And because poor people may not be destitute of emploiment, upon suspicion of being servants, and servants also kept from running away, Be it enacted, by the authority aforesaid, and it is hereby enacted, That every servant, when his or her time of service shall be expired, shall repair to the court of the county where he or she served the last of his or her time, and there, upon sufficient testimony, have his or her freedom entered; and a certificate thereof from the clerk of the said court, shall be sufficient to authorise any person to entertain or hire such servant, without any danger of this law. And if it shall at any time happen, that such certificate is worn out, or lost, the said clerk shall grant a new one, and therein also recite the accident happened to the old one. And whoever shall hire such servant, shall take his or her certificate, and keep it, ‘till the contracted time shall be expired. And if any person whatsoever, shall harbour or entertain any servant by importation, or by contract, or indenture made here, not having such certificate, he or she so offending, shall pay to the master or owner of such servant, sixty pounds of tobacco for every natural day he or she shall so harbour or entertain such runaway: To be recovered, with costs, by action of debt, in any court of record within this her majesty’s colony and dominion, where in no essoin, protection, or wager of law, shall be allowed. And also, if any runaway shall make use of a forged certificate, or after the same shall be delivered to any master or mistress, upon being hired, shall steal the same away, and thereby procure entertainment, the person entertaining such servant, upon such forged or stolen certificate, shall not be culpable by this law: But the said runaway, besides making reparation for the loss of time, and charges in recovery, and other penalties by this law directed, shall, for making use of such forged or stolen certificate, or for such theft aforesaid, stand two hours in the pillory, upon a court day: And the person forging such certificate, shall forfeit and pay ten pounds current money; one half thereof to be to her majesty, her heirs and successors, for and towards the support of this government and the contingent charges thereof; and the other half to the master or owner of such servant, if he or she will inform or sue for the same, otherwise to the informer: To be recovered, with costs, by action of debt, bill, plaint or information, in any court of record in this her majesty’s colony and dominion, wherein no essoin, protection, or wager of law, shall be allowed. And if any person or persons convict of forging such certificate, shall not immediately pay the said ten pounds, and costs, or give security to do the same within six months, he or she so convict, shall receive, on his or her bare back, thirty-nine lashes, well laid on, at the common whipping post of the county; and shall be thence discharged of paying the said ten pounds, and costs, and either of them.

XXII. Provided, That when any master or mistress shall happen to hire a runaway, upon a forged certificate, and a servant deny that he delivered any such certificate, the Onus Probandi shall lie upon the person hiring, who upon failure therein, shall be liable to the fines and penalties, for entertaining runaway servants, without certificate.

XXIII. And for encouragement of all persons to take up runaways, Be it enacted, by the authority aforesaid, and it is hereby enacted, That for the taking up of every servant, or slave, if ten miles, or above, from the house or quarter where such servant, or slave was kept, there shall be allowed by the public, as a reward to the taker-up, two hundred pounds of tobacco; and if above five miles, and under ten, one hundred pounds of tobacco: Which said several rewards of two hundred, and one hundred pounds of tobacco, shall also be paid in the county where such taker-up shall reside, and shall be again levied by the public upon the master or owner of such runaway, for re-imbursement of the same to the public. And for the greater certainty in paying the said rewards and re-imbursement of the public, every justice of the peace before whom such runaway shall be brought, upon the taking up, shall mention the proper-name and sur-name of the taker-up, and the county of his or her residence, together with the time and place of taking up the said runaway; and shall also mention the name of the said runaway, and the proper-name and sur-name of the master or owner of such runaway, and the county of his or her residence, together with the distance of miles, in the said Justice’s judgment, from the place of taking up the said runaway, to the house or quarter where such runaway was kept.

Act 23 deals with the rewards of any person who captures a servant or an enslaved person. If either is captured more than ten miles from the plantation they serve, the reward for the person apprehending was two hundred pounds of tobacco. If a servant or enslaved person was captured between five to ten miles from their plantation, the reward was one hundred pounds of tobacco. The rewards for the capture of servants and enslaved people was paid by the public at large.

XXIV. Provided, That when any negro, or other runaway, that doth not speak English, and cannot, or through obstinacy will not, declare the name of his or her master or owner, that then it shall be sufficient for the said justice to certify the same, instead of the name of such runaway, and the proper name and sur-name of his or her master or owner, and the county of his or her residence and distance of miles, as aforesaid; and in such case, shall, by his warrant, order the said runaway to be conveyed to the public goal [jail], of this country, there to be continued prisoner until the master or owner shall be known; who upon, paying the charges of the imprisonment, or giving caution to the prison-keeper for the same, together with the reward of two hundred or one hundred pounds of tobacco, as the case shall be, shall have the said runaway restored.

XXV. And further, the said justice of the peace, when such runaway shall be brought before him, shall, by his warrant commit the said runaway to the next constable, and therein also order him to give the said runaway so many lashes as the said justice shall think fit, not exceeding the number of thirty-nine; and then to be conveyed from constable to constable, until the said runaway shall be carried home, or to the country goal, as aforesaid, every constable through whose hands the said runaway shall pass, giving a receipt at the delivery; and every constable failing to execute such warrant according to the tenor thereof, or refusing to give such receipt, shall forfeit and pay two hundred pounds of tobacco to the church-wardens of the parish wherein such failure shall be, for the use of the poor of the said parish: To be recovered, with costs, by action of debt, in any court of record in this her majesty’s colony and dominion, wherein no essoin, protection or wager of law, shall be allowed. And such corporal punishment shall not deprive the master or owner of such runaway of the other satisfaction here in this act appointed to be made upon such servant’s running away.

XXVI. Provided always, and be it further enacted, That when any servant or slave, in his or her running away, shall have crossed the great bay of Chesapeak, and shall be brought before a justice of the peace, the said justice shall, instead of committing such runaway to the constable, commit him or her to the sheriff, who is hereby required to receive every such runaway, according to such servant, and to cause him, her, or them, to be transported again across the bay, and be delivered to a constable there; and shall have, for all his trouble and charge herein, for every such servant or slave, five hundred pounds of tobacco, paid by the public; which shall be re-imbursed again by the master or owner of such runaway, as aforesaid, in manner aforesaid.

XXVII. Provided also, That when any runaway servant that shall have crossed the said bay, shall get up into the country, in any county distant from the bay, that then, in such case, the said runaway shall be committed to a constable, to be conveyed from constable to constable, until he shall be brought to a sheriff of some county adjoining to the said bay of Chesapeak, which sheriff is also hereby required, upon such warrant, to receive such runaway, under the rules and conditions aforesaid; and cause him or her to be conveyed as aforesaid; and shall have the reward, as aforesaid.

XXVIII. And for the better preventing of delays in returning of such runaways, Be it enacted, That if any sheriff, under sheriff, or other officer of, or belonging to the sheriffs, shall cause of suffer any such runaway (so committed for passage over the bay) to work, the said sheriff, to whom such runaway shall be so committed, shall forfeit and pay to the master or owner, of every such servant or slave, so put to work, one thousand pounds of tobacco; To be recovered, with costs, by action of debt, bill, plaint, or information, in any court of record within this her majesty’s colony and dominion, wherein no essoin, protection, or wager of law, shall be allowed.

XXIX. And be it enacted, by the authority aforesaid, and it is hereby enacted, That if any constable, or sheriff, into whose hands a runaway servant or slave shall be committed, by virtue of this act, shall suffer such runaway to escape, the said constable or sheriff shall be liable to the action of the party grieved, for recovery of his damages, at the common law with costs.

XXX. And also be it enacted, by the authority aforesaid, and it is hereby enacted, That every runaway servant, upon whose account, either of the rewards aforementioned shall be paid, for taking up, shall for every hundred pounds of tobacco so paid by the master or owner, serve his or her said master or owner, after his or her time by indenture, custom, or former order of court, shall be expired, one calendar month and an half, and moreover, shall serve double the time such servant shall be absent in such running away; and shall also make reparation, by service, to the said master or owner, for all necessary disbursements and charges, in pursuit and recovery of the said runaway; to be adjudged and allowed in the county court, after the rate of one year for eight hundred pounds of tobacco, and so proportionably for a greater or lesser quantity.

XXXI. Provided, That the masters or owners of such runaways, shall carry them to court the next court held for the said county, after the recovery of such runaway, otherwise it shall be in the breast of the court to consider the occasion of delay, and to hear, or refuse the claim, according to their discretion, without appeal for the refusal.

XXXII. And also be it enacted, by the authority aforesaid, and it is hereby enacted, That no master, mistress, or overseer of a family, shall knowingly permit any slave, not belonging to him or her, to be and remain upon his or her plantation, above four hours at any one time, without the leave of such slave’s master, mistress, or overseer, on penalty of one hundred and fifty pounds of tobacco to the informer, cognizable by a justice of the peace of the county wherein such offence shall be committed.

Act 32 is a reissuing of the 1682 law restricting movement of enslaved persons by limiting how long they can remain on a neighboring plantation without a certificate or pass. The only change in this law is that the penalty against the enslaver went from two hundred pounds to one hundred and fifty pounds and said penalty to go to the informer.

XXXIII. Provided also, That if any runaway servant, adjudged to serve for the charges of his or her pursuit and recovery, shall, at the time, he or she is so adjudged, repay and satisfy, or give good security before the court, for repaiment and satisfaction of the same, to his or her master or owner, within six months after, such master or owner shall be obliged to accept thereof, in lieu of the service given and allowed for such charges and disbursements.

XXXIV. And if any slave resist his master, or owner, or other person, by his or her order, correcting such slave, and shall happen to be killed in such correction, it shall not be accounted felony; but the master, owner, and every such other person so giving correction, shall be free and acquit of all punishment and accusation for the same, as if such accident had never happened: And also, if any negro, mulatto, or Indian, bond or free, shall at any time, lift his or her hand, in opposition against any christian, not being negro, mulatto, or Indian, he or she so offending, shall, for every such offence, proved by the oath of the party, receive on his or her bare back, thirty lashes, well laid on; cognizable by a justice of the peace for that county wherein such offence shall be committed.

Before slavery became codified into Virginia law, Africans had some protections much as indentured servants did. But after the 1662 law that codified and legalized slavery by tying the institution to the status of the mother, all enslaved people’s rights were void. As chattel, enslaved people no longer were viewed as people, but as a commodity and a piece of property. Act 34 of the 1705 Slave Codes is an updated reinforcement of the 1669 “Casual Killing Act”. How was this law updated? It’s all in the language used. If an enslaved person was killed in correction, then the white person who committed the killing (let’s be honest, it was murder) would be acquit “as if such accident had never happened.” This is further debasement of the African American and Black race of people in the colony. This was, and is, racism at its worst. And as mentioned, the enslaved had no recourse since they had no rights and could not testify against a white person in court. Prior to the 1705 Slave Codes, there were no cases of an enslaver or overseer having been taken to court for the murder of an enslaved person. The only exceptions were those such as the previously mentioned William Pitman case in Williamsburg in 1775. In that case, Pitman was only brought to justice for having killed his enslaved boy because his own children testified against him in court.

XXXV. And also be it enacted, by the authority aforesaid, and it is hereby enacted, That no slave go armed with gun, sword, club, staff, or other weapon, nor go from off the plantation and seat of land where such slave shall be appointed to live, without a certificate of leave in writing, for so doing, from his or her master, mistress, or overseer: And if any slave shall be found offending herein, it shall be lawful for any person or persons to apprehend and deliver such slave to the next constable or head-borough, who is hereby enjoined and required, without further order or warrant, to give such slave twenty lashes on his or her bare back, well laid on, and so send him or her home: And all horses, cattle, and hogs, now belonging, or that hereafter shall belong to any slave, or of any slaves mark in this her majesty’s colony and dominion, shall be seised and sold by the church-wardens of the parish, wherein such horses, cattle, or hogs shall be, and the profit thereof applied to the use of the poor of the said parish: And also, if any damage shall be hereafter committed by any slave living at a quarter where there is no christian overseer, the master or owner of such slave shall be liable to action for the trespass and damage, as if the same had been done by him or herself.

Act 35 reinforces the 1640 act restricting gun ownership to whites only and the 1680 “act for preventing Negroes Insurrections.” This act which further limited the movements of the enslaved, also added a new punishment against enslaved who violated this law. Enslaved people could have what little personal property they were allowed—horses, cattle, or hogs—taken from them to be sold by the parish in which they reside for the benefit of the poor.

XXXVI. And also it is hereby enacted and declared, That baptism of slaves doth not exempt them from bondage; and that all children shall be bond or free, according to the condition of their mothers, and the particular directions of this act.

Act 36 reinforces the 1662 act “Negro womens children to serve according to the condition of the mother” and the 1667 act “declaring that baptisme of slaves doth not exempt them from bondage.” One of the last successful cases of an enslaved person being able to obtain their freedom by the fact of their being Christian was the case of previously mentioned Elizabeth Key.

XXXVII. And whereas, many times, slaves run away and lie out, hid and lurking in swamps, woods, and other obscure places, killing hogs, and committing other injuries to the inhabitants of this her majesty’s colony and dominion, Be it therefore enacted, by the authority aforesaid, and it is hereby enacted, That in all such cases, upon intelligence given of any slaves lying out, as aforesaid, any two justices (Quorum unus) of the peace of the county wherein such slave is supposed to lurk or do mischief, shall be and are impowered and required to issue proclamation against all such slaves, reciting their names, and owners names, if they are known, and thereby requiring them, and every of them, forthwith to surrender themselves; and also impowering the sheriff of the said county, to take such power with him, as he shall think fit and necessary, for the effectual apprehending such out-lying slave or slaves, and go in search of them: Which proclamation shall be published on a Sabbath day, at the door of every church and chapel, in the said county, by the parish clerk, or reader, of the church, immediately after divine worship: And in case any slave, against whom proclamation hath been thus issued, and once published at any church or chapel, as aforesaid, stay out, and do not immediately return home, it shall be lawful for any person or persons whatsoever, to kill and destroy such slaves by such ways and means as he, she, or they shall think fit, without accusation or impeachment of any crime for the same: And if any slave, that hath run away and lain out as aforesaid, shall be apprehended by the sheriff, or any other person, upon the application of the owner of the said slave, it shall be made lawful for the county court, to order such punishment to the said slave, either by dismembering, or any other way, not touching his life, as they in their discretion shall think fit, for the reclaiming any such incorrigible slave, and terrifying others from the like practices.

Act 37 is particularly heinous in that any slaves caught hiding out could be killed by any white person by any means, with impunity. As this law was a reinforcement of the 1680 act, this act was meant to strike fear in the enslaved class and prevent them from running away and going into hiding. The law allowed the county courts to order punishments for captured enslaved people including dismemberments. Dismemberment would usually be in public and could include being branded, whippings, and having toes and or fingers severed as a warning to others to desist in their efforts to escape.

XXXVIII. Provided always, and it is further enacted, That for every slave killed, in pursuance of this act, or put to death by law, the master or owner of such slave shall be paid by the public:

XXXIX. And to the end, the true value of every slave killed, or put to death, as aforesaid, may be the better known; and by that means, the assembly the better enabled to make a suitable allowance thereupon, Be it enacted, That upon application of the master or owner of any such slave, to the court appointed for proof of public claims, the said court shall value the slave in money, and the clerk of the court shall return a certificate thereof to the assembly, with the rest of the public claims.

Acts 38 and 39 deal with the reimbursing slave owners in the event that one of their enslaved people are killed under any circumstance tied to any of the acts passed under this legislative session of the House of Burgesses, as well as the manner in which they are valued. Owners were to be compensated by the public at large for the loss of any enslaved person upon the application to the colony to be valued for the amount due the owner. How do you value the loss of these human beings? Well, they were not viewed as human beings. The loss to their enslaved family members was not considered, only the loss to the owner of these people. They were property, they were a commodity, they were a means to providing wealth and prosperity.

XL. And for the better putting this act in due execution, and that no servants or slaves may have pretense of ignorance hereof, Be it also enacted, That the church-wardens of each parish in this her majesty’s colony and dominion, at the charge of the parish, shall provide a true copy of this act, and cause entry thereof to be made in the register book of each parish respectively; and that the parish clerk, or reader of each parish, shall, on the first sermon Sundays in September and March, annually, after sermon or divine service is ended, at the door of every church and chapel in their parish, publish the same; and the sheriff of each county shall, at the next court held for the county, after the last day of February, yearly, publish this act, at the door of the court-house: And every sheriff making default herein, shall forfeit and pay six hundred pounds of tobacco; one half to her majesty, her heirs, and successors, for and towards the support of the government; and the other half to the informer. And every parish clerk, or reader, making default herein, shall, for each time so offending, forfeit and pay six hundred pounds of tobacco; one half whereof to be to the informer; and the other half to the poor of the parish, wherein such omission shall be: To be recovered, with costs, by action of debt, bill, plaint, or information, in any court of record in this her majesty’s colony and dominion, wherein no essoin, protection, or wager of law, shall be allowed.

XLI. And be it further enacted, That all and every other act and acts, and every clause and article thereof, heretofore made, for so much thereof as relates to servants and slaves, or to any other matter or thing whatsoever, within the purview of this act, is and are hereby repealed, and made void, to all intents and purposes, as if the same had never been made.

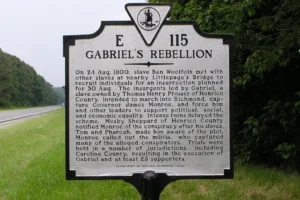

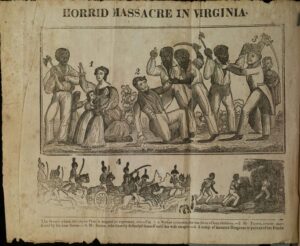

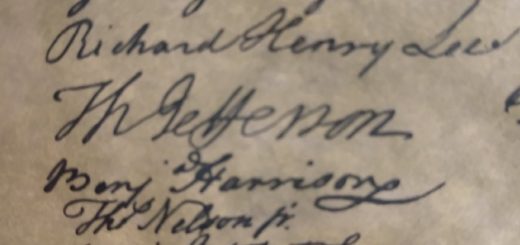

The final clause in act 41, voided all previous laws that were passed and established all of the acts of 1705 as the new law of the colony as regarded servants and enslaved people. Additional laws would be passed over the next 150 years further limiting the rights, movements, and altering the lives of those enslaved in Virginia and elsewhere. Rumors of insurrections by the enslaved such as Gabriel’s Rebellion in Richmond and rebellions that were carried out completely such as Nat Turner’s Rebellion in Southampton County in 1831, prompted the passing of more laws. These laws were meant to restrict the enslaved from being educated–which it was believed could lead to seeking freedom–and from meeting by stoking fear in those who sought to plan and lead rebellions. And the punishments towards those who led these failed rebellions and those who supported them became more heinous in nature. Gabriel Prosser, after being captured, was hung on October 10, 1800. Nat Turner after being captured, faced one of the most horrific of punishments documented. First, he was hung in Jerusalem, Virginia on November 11, 1831. Nat Turner was then beheaded–in 2016 what is believed to have been Turner’s skull was returned to two of his descendants and is now at the Smithsonian pending DNA testing–and his body was skinned and dissected. It is said that purses were even made from some of his skin.

Historic Marker for Gabriel’s Rebellion in Henrico County, Virginia.

Authentic and Impartial Narrative of the Tragical Scene Which was Witnessed in Southampton County (Virginia) on Monday the 22d of August Last, When Fifty-five of its Inhabitants (mostly women and children) were inhumanly Massacred by the Blacks! A 1831 .W377. Special Collections, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Va. Courtesy of University of Virginia Special Collections.

Though Virginia was not the first colony to legalize slavery–Massachusetts became the first colony to legalize slavery in 1641–the laws passed by Virginia in the 17th century became the foundational basis for the laws passed as part of the 1705 “Act concerning Servants and Slaves.” The laws passed in the 17th century took Virginia from a society with slaves to a slave society and helped make the practice race based, which in turn legalized racism in the colonies and the future United States. Untold numbers of enslaved people were killed or maimed in execution of these laws. The dignity, rights, and lives of the enslaved were taken from them, all in the pursuit of wealth and prosperity for some, at the expense of others. These laws became the foundation of chattel slavery for other colonies and future states. Through the use of fear, these laws restricted every facet of life for those enslaved.

I often wonder, what could have been if slavery did not come into existence in the colonies and the future United States. Would the Revolutionary War have lasted as long if we had larger numbers of African American and Black people fighting for the patriot cause? What if the founders had erased slavery all together at the founding of our nation? Would the Civil War have happened and caused the deaths of more than 700,000 people? Racism, I think, would still have been there, but would it have been as bad had slavery not occurred? Would lynchings have occurred and would Jim Crow and the Civil Rights Movement have been necessary? All that is left to us is the breadcrumbs that history spreads for us. It is left to us who are to decipher and tell the stories.

References

Affidavit, 1693. Virginia Museum of History and Culture, accessed 22 October 2025. https://virginiahistory.org/learn/affidavit-1693.

Billings, Warren M. The Old Dominion in the Seventeenth Century: A Documentary History of Virginia 1606-1700. Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Hening, William Waller. The Statutes at Large; Being A Collection Of All The Laws of Virginia, From The First Session Of The Legislature, In The Year 1619. Volume 1. University Press of Virginia, 1969. First published in 1823 by R. & W. & G. Bartow.

Hening, William Waller. The Statutes at Large; Being A Collection Of All The Laws of Virginia, From the First Session Of The Legislature, In The Year 1619. Volume 2. University Press of Virginia, 1969. First published in 1823 by R. & W. & G. Bartow.

Hening, William Waller. The Statutes at Large; Being A Collection Of All The Laws of Virginia, From The First Session Of The Legislature, In The Year 1619. Volume 3. University Press of Virginia, 1969. First published in 1823 by R. & W. & G. Bartow.

Very interesting article! I really enjoyed reading this.

Thanks mom, my biggest cheerleader. Love you.

Thank you for summarizing some of the laws in your article, Todd. It really clarified some of the lengthier laws presented. I taught Nat Turner’s Rebellion, but the history books never described his horrendous punishment, which probably for elementary students would not have been appropriate. You presented some very thought provoking questions in your summarization of the article. Another great job!

Thank you, LaVerne, for following and reading my work. Yes, with many of my articles, I try to deep dive more and ask and answer questions I myself have to get to the root of the events of history. Nat Turner, Elizabeth Key, John Punch, all of them and their cases, helped to prompt additions to laws that were passed in restricting those enslaved in Virginia and elsewhere. But yes, you are correct, some of this stuff is a little to much for elementary school students. I remember learning of Nat Turner in grade school, but it never really went into great detail. It wasn’t until Longwood that I learned in depth as to the full history of Turner’s Rebellion. I hope you and Sam have a great Thanksgiving.