Slavery and Its Effect on the New Territories of the American Frontier

Slavery played a large and important role in the new and forming territories in the Western frontier that were acquired through the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 and with the defeat of Mexico in 1848 in the Mexican War. When the United States acquired these vast territories, many questions arose. The biggest question that came up was, how would slavery affect and fit into these territories? Slavery was at the forefront of the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and the Compromise of 1850 when new territories were applying for statehood. The idea of the compromises was that if both the Northern faction and the Southern faction gave a little, they would gain something in return. Through the provisions of these two compromises the nation was able to temporarily avoid conflict that could have and would have torn the nation apart sooner than it did. But the compromises did not solve the problem of slavery’s extension into the new territories. Ultimately the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854 would render the compromises null and void. The events of the Kansas-Nebraska Act would eventually lead to conflict and turmoil in the new territories and would also affect the organization, goals, and ideas of the political parties of the times causing them to split on the issue of slavery in the new territories. All the events involved with Kansas-Nebraska set the stage for secession of the Southern states in 1860 and 1861 and led to the American Civil War.

Louisiana Purchase of 1803.

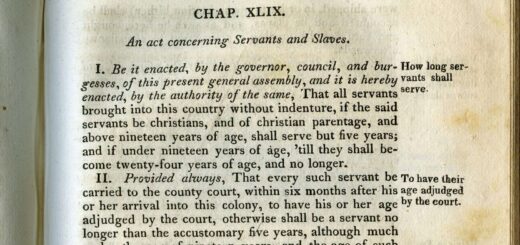

In 1803 the United States purchased the Louisiana Territory from France for $15 million. With the acquisition of this vast amount of land, the question arose on how slavery would fit into the new territory. An answer to the question came when the Missouri Territory, which was part of the land gained in the Louisiana Purchase, applied for statehood in 1819. At this point in time there was an equal balance of power in Congress with eleven free states and eleven slave states. Missouri’s application for statehood caused an issue with the balance of power because the North wanted Missouri to be a free state and the South wanted it to be a slave state. Both the North and the South were worried the other would gain an upper hand in Congress. Because of the fear of a possible shift in the balance of power, the threat of disunion became a serious issue and worried many people throughout the country. There was concern in the North that the South would gain a representational advantage if Missouri were to become a slave state, so New York congressman James Tallmadge presented “an amendment that would prohibit any further growth of slavery in Missouri, and would eventually set the children of Missouri’s slaves free.” Tallmadge’s amendment passed in the House of Representatives but when the amendment reached the Senate it “encountered a furious opposition and was rejected by a large majority.”

Into the mix stepped Henry Clay, a Kentuckian who had served several terms in both the House of Representatives and the Senate. His involvement in the Missouri Compromise and the Compromise of 1850 would be important to avoiding conflict and keeping the nation together. Clay proposed a compromise plan which included both the territories of Missouri and Maine. Maine had been a territory of Massachusetts that wanted to break away from Massachusetts to form its own state. There was opposition by the North and South to parts of Clay’s plan so his plan was not accepted. Since there were parts of Clay’s proposal that would benefit both the pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions on the issue of Missouri, a two-part compromise was created.

Henry Clay in 1848.

The “compromise bill was carried, March 2, 1820, by a vote of 134 against 42” therefore accepting the terms it offered. There were four major provisions that composed the compromise. The first two provisions were that Missouri was to be admitted into the Union as a slave state and Maine was to be admitted into the Union as a free state. Both states were also to be admitted to the Union on an equal basis. These two provisions benefited both the anti-slavery and pro-slavery factions and also maintained the balance of power with twelve slave states and twelve free states. The third provision in the Missouri Compromise stated with the exception of Missouri, there was to be an invisible line drawn at 36° 30’ north latitude that banned slavery above that line. This provision benefitted both sides. In the South in that it allowed slavery in the new territories south of the 36° 30’ line. The 36° 30’ provision benefitted the North in that it banned slavery in new territories north of that line with the exception of Missouri. In other words both sides gave a little to gain something in return. The North conceded allowing slavery south of 36° 30’ to gain a restriction north of that line as where the South conceded the restriction of slavery north of 36° 30’ to gain unrestricted slavery south of that line. The fourth provision of the compromise stated fugitive slaves “escaping into any…state or territory of the United States…may be lawfully reclaimed and conveyed to the person claiming his or her labour or service.” Maine was admitted into the Union on March 15, 1820 and Missouri was admitted on August 10, 1820. The Missouri Compromise accomplished its goal and avoided conflict, at least temporarily. Henry Clay was “acclaimed as the ‘Great Pacificator’” for the role he played in helping to construct the Missouri Compromise.

Thirty years later the issue of how slavery would fit into new territories sprang up again. In 1848 the United States defeated Mexico in the Mexican War. Once again, as a result of the American victory in the Mexican War, the United States gained vast amounts of territory in areas that would become the states of Utah, New Mexico, California, Arizona, and Nevada. Threats of disunion in Southern states, because of the issue of slavery in the new territories, were greater than they were in the Missouri Compromise. On the issue of slavery in the new territories, the South felt as if it’s involvement in the new territories was being left out. There were three additional issues that arose out of the acquirement of new territory. One issue that came to surface was that Texas claimed the territory of New Mexico all the way to Santa Fe. Another issue that surfaced was the existence of slavery and the slave trade in the District of Columbia. Once again, the balance of power issue resurfaced because California wanted to be admitted into the Union as a free state. If California was to be admitted as a free state, the balance of power would shift to thirteen free states and twelve slave states. Just as one would figure the South did not like the idea of allowing the North to have an advantage in the House of Representatives and the Senate because the institution of slavery would be threatened in the new territories. John C. Calhoun “warned that Union could survive only if the North and South shared equal power within it.”

On January 29, 1850, Henry Clay presented a compromise that was debated by Congress for the next eight months. The members of Congress were led by Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, a senator from Massachusetts, and John C. Calhoun, a Senator from South Carolina. Also, “with the help of Stephen Douglas, a young democrat from Illinois, a series of bills that would make up the compromise were ushered through Congress.” The resolutions in the compromise had portions that the pro-compromise and the anti-compromise factions liked and disliked. The idea in the construction of the compromise was that both factions of the compromise would vote for the parts of the compromise they liked although they were conceding the parts they did not like.

All of the bills that were included in the compromise were passed between September 9th and September 20, 1850. There were five parts of the compromise that solved the issues at hand. The idea of popular sovereignty solved the problem of how slavery would fit into the territories of New Mexico, Nevada, Arizona, and Utah. The concept of popular sovereignty, which arose out of this compromise, was “that Congress should stay out of the controversy and let the territories decide for themselves as they became states whether or not to be slave or free.” On the issue of Texas’s claim to the New Mexico territory, Texas would have to cede that claim but in return would receive $10 million which the state could and would use the money to pay off its debt to Mexico as well as its national debt. To resolve the issue of slavery and slave trade within the limits of Washington, D.C., slave trade was exterminated but the institution of slavery was still allowed within Washington’s borders. On the issue of California throwing off the balance of power, California “would be admitted as a free state,” but “to pacify slave-state politicians, who would have objected to the imbalance created by adding another free state, the Fugitive Slave Act was passed.”

The Fugitive Slave Act was created to satisfy the pro-slavery faction since California was admitted as a free state. The Fugitive Slave Act provided that citizens had to turn over any fugitive slaves who escaped to the North. The act also suspended a fugitive slave’s right to a trial by jury, in case that slave made an attempt to sue for freedom. In some cases free blacks in the North were claimed by southern slave owners and shipped down South into slavery. The free blacks of the North had “no legal right to plead their cases,” therefore leaving them “completely defenseless.” This act seemed to be a good addition to the compromise on paper but in all reality all it did was do more harm than good. Some people in the North saw the act “as a direct aggression by the Slave Power on the republican rights and liberties of Northern whites.” The Fugitive Slave Act strengthened the abolitionist movements resolve to do away with the institution of slavery. Also as a result of the act and compromise, the Underground Railroad became more active in the period between 1850 and 1860. The Fugitive Slave Act also changed many people’s stance on slavery in that “many that had previously been ambivalent about slavery now took a definitive stance against the institution.” The Compromise was a success in that it avoided disunion over the issues at hand but the compromise did not ameliorate the situation permanently. The issue of slavery was too deep and too controversial an issue to avoid the conflict that was to come a decade later.

The Compromise of 1850 solved the problem over the extension of slavery into the new territories, but only temporarily. The issue of slavery’s extension into the new territories arose again in 1853 when Stephen A. Douglas, who helped get the Compromise of 1850 through Congress and William A. Richardson, produced a bill for the formation of the Nebraska territory. The bill quickly passed in the House but faced opposition from southern senators therefore not allowing it to pass in the Senate. One southerner who opposed the bill by Douglas and Richardson was David Atchison of Missouri. Atchison was the president pro tempore of the Senate and was a defender of southern states rights. If the bill passed Atchison said Missouri would, “be surrounded by free territory….With the emissaries of abolitionists around us….this species of property would become insecure,” therefore he and his supporters opposed the move to organize the Nebraska territory. The F Street Mess, which was a group of Southern senators who were opposed to the formation of the Nebraska territory, consisted of David Atchison, James Mason and Robert M. T. Hunter of Virginia, and Andrew P. Butler of South Carolina. The F Street Mess sent a notice to Stephen Douglas saying if he “wanted Nebraska he must repeal the ban of bondage there and place ‘slaveholder and non-slaveholder upon terms of equality’”. Douglas was caught in a tight spot, one that would cause political and social upheaval with whatever the outcome would be. Douglas knew if he repealed the ban of slavery above the 36° 30’ line that it would nullify the Missouri Compromise and would cause a serious uproar in the North. If he didn’t appeal the ban then his bill to organize the territory of Nebraska would face serious opposition from the South and most likely not pass.

Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois.

To come up with a solution Douglas tried to work around the Missouri Compromise and the popular sovereignty part of the Compromise of 1850 that would allow the territory to decide for itself whether to have slavery. This was not satisfying enough for Atchison and other southerners. Douglas ended up doing what he did not want to do by adding to his bill the repeal of the 36° 30’ ban and also provided for the organization of two territories, above the line the settlers of the territory could choose whether or not to allow slavery. With the exception of Secretary of War Jefferson Davis and Secretary of the Navy James Dobbin, the Democratic president, Franklin Pierce and his cabinet shot down Douglas’s repeal bill. Angered by Pierce’s rejection of Douglas’s revised Kansas-Nebraska bill, the F Street Mess gave President Pierce an ultimatum: support the repeal of the ban of slavery above the 36° 30’ line or loose the South. Caught in a bad position, Pierce gave in to the F Street Mess’s threat. The Kansas-Nebraska Act was passed in the House of Representatives on May 22, 1854 by a vote of 113 to 100 and was signed into law on May 30, 1854 by President Pierce.

Vote for/against the Kansas-Nebraska Act

| Party | For | Against |

| Southern Democrats | 57 | 4 |

| Northern Democrats | 43 | 43 |

| Southern Whigs | 13 | 5 |

| Northern Whigs | 0 | 41 |

| Free-Soil Party | 0 | 4 |

| Total | 113 | 100 |

Just as Douglas expected, the bill caused opposition in the North. William Pitt Fessenden, who was a Whig Senator from Maine, thought of Douglas’s bill as “a terrible outrage…The more I look at it the more enraged I become. It needs little to make me an out & out abolitionist.” On May 20, 1854 John W. Edmands, who was a Whig and a member of the House of Representatives, gave a speech to the House of Representatives showing his opposition “to the Kansas-Nebraska bill on principle and expediency.” Edmands said in his speech that the South’s “aggression of slavery is the main feature of the movement now being made.” Also in his speech Edmands made a comment stating that “They will send out their people by thousands; and, sir, you may judge what disposition towards slavery such settlers will possess.” This comment could be viewed as a premonition to the conflict which would occur in what would become known as “Bleeding Kansas.” The passing of the Kansas-Nebraska Act also had political consequences as well.

With the passing of the Kansas-Nebraska Act came a large scale and bloody conflict in the territory of Kansas. In November of 1855 a proslavery man killed a free-soil settler which in turn helped to set off the conflict in Kansas. The conflict and events in Kansas would gain the territory the nickname of “Bleeding Kansas.” The conflict in Kansas was between the two rival factions of the free-soil abolitionists and the proslavery Missourians also known as “Border Ruffians.” One place where such violence between these two factions would take place was in Lawrence, Kansas. Lawrence was the center and safe haven for free-soil and abolitionist activity in Kansas. After the murder of the free-soil settler in 1855 about 1,500 Border Ruffians headed for Lawrence and upon arrival were met by some 1,000 free-soilers who were armed with Sharps rifles and a piece of artillery. The governor of the territory, Wilson Shannon, was able to deescalate the situation in which both sides stood down. But this was not the first or last time a situation like this would occur in Lawrence. The following year on May 21, 1856 a contingent of some 800 Border Ruffians went to Lawrence with five pieces of artillery and shelled the town. These men burned the home of the governor, burned the hotel, raided shops and homes. Nobody in the town was killed in the process of the raid but the Eastern Republic press contained headlines such as “The War Actually Begun-Triumph of the Border Ruffians-Lawrence in Ruins-Several Persons Slaughtered-Freedom Bloodily Subdued.” The raid of Lawrence would inspire an abolitionist named John Brown to retaliate for the raid.

On the night of May 24th and the morning of May 25, 1856, angered by the events in Lawrence, John Brown led a small group of men which he called the Army of the North to Pottawatomie Creek to strike a blow against the proslavery faction in Kansas. Brown and his men came up on the home of James Doyle and his family. James Doyle was active in the activities of the proslavery faction in Kansas. Brown and his men took Doyle and his two older sons away and hacked them to death with military style broadswords. Brown and his men went to more homes along Pottawatomie Creek and murdered two more men, one by the name of Wilkinson and the other named William Sherman. A few years later Brown would end up leading a raid in Harpers Ferry, Virginia in October 1859 and in the process of the raid he and his men raided the United States arsenal which was located in Harpers Ferry. Brown was then captured by United States Marines led by Colonel Robert E. Lee. Brown was tried, found guilty for his actions, and sentenced to be hung on December 2, 1859 for his raid on Harpers Ferry. The events in Kansas and Harpers Ferry would help, as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow said, to sow “the wind to reap the whirlwind, which will come soon.” The whirlwind described by Longfellow would be what would become the American Civil War. One could not say these events caused the Civil War, but they helped to set the stage for what happened on April 12, 1861 in Charleston, South Carolina.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act not only had an effect on the territory of Kansas, but it also had an effect on the politics of the time. The two rival political parties of this era in our nation’s history were the Democratic Party and the Whig Party. The Democratic Party formed in the middle 1790s to oppose the Federalist Party and its policies. The Whig Party formed around 1833-34 to oppose the Democratic Party and the policies of President Andrew Jackson. Throughout its existence, the Whig Party experienced factionalism which would ultimately hurt its structure and cause its collapse. The last Whig president, Millard Fillmore, helped push the Compromise of 1850 through Congress in the hopes that it would end the controversy over slavery. The Compromise of 1850 was a good example to show how the parties, both northern and southern factions, were split over issues such as slavery. Northern Whigs and Southern Democrats were anti-compromise while Southern Whigs and Northern Democrats were pro-compromise. Northern Whigs and Democrats both were disgusted when the Kansas-Nebraska Act was passed. The signing of the Kansas-Nebraska Act into law “permanently severed the Northern and Southern wings of the Whig party and eventually obliterated what remained of it in the South.” Senator Truman Smith of Connecticut said that “the Whig party has been killed off effectually by that miserable Nebraska business.” Senator Smith would end up resigning from the Senate in response to the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Some of the Northern Democrats who voted against the act ended up leaving the Democratic Party and some jumped ship to the opposite party. With the signing of the Kansas-Nebraska Act and the election in 1856 of James Buchanan as president, the Whig Party collapsed from a lack of support in the election. With the collapse of the Whig Party came the rise of a new, completely northern, Republican Party. The election of the Republican presidential candidate Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 election is what finally led to the secession of the cotton states in 1860-61 and led to the American Civil War.

Slavery proved to be one of the greatest, most controversial, and complex issues to affect our country’s formation. With the acquisition of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803 and the land gained from the Mexican War which ended in 1848 came concern for how slavery would fit into the new territories. The first true test of how slavery would fit into the new territories came with the Compromise of 1820 which found a temporary solution to the problem. Thirty years later the organization of the territories gained from the Mexican War brought slavery back to the front of issues concerning the country and once again another temporary solution was reached. The idea of these compromises was to give a little and gain a little in return which worked for only brief periods of time. But the concern of slavery’s expansion caused things to spiral out of control when the Kansas-Nebraska Act was passed. Conflict and turmoil ensued in Kansas. The Kansas-Nebraska Act also caused political parties to split into separate factions which in the end would lead to the collapse of the Whig Party. The people involved with all the events mentioned in this article played pivotal roles in the issue of slavery and how it would and did fit into the new territories. Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, John C. Calhoun, and Stephen A. Douglas were important when it came to finding solutions to slavery to keep the nation from dividing on the question of slavery. But after Clay, Webster, and Calhoun died there was nobody who had their genius and ideals to come up with solutions to the problems slavery presented. John Brown’s ventures led other abolitionists to rally to prevent the spread of slavery and it was his acts what would help to set the stage for the United States’ greatest internal conflict in history, the American Civil War.

References

Blaine, James G. “The Missouri Compromise.” (2000). Accessed 4 October 2007. http://www.historycentral.com/documents/Miscompromise.html.

Congressional Globe, Senate, 33rd Cong., 1st Sess. 752 (1854). Accessed 18 November 2007. http://memory.loc.gov/ll/llcg/036/0700/07600752.gif.

Congressional Globe, Senate, 33rd Cong., 1st Sess. 754 (1854). Accessed 18 November 2007.

http://memory.loc.gov/ll/llcg/036/0700/07600754.gif.

Congressional Globe, Senate, 33rd Cong., 1st Sess. 755 (1854). Accessed 18 November 2007.

http://memory.loc.gov/ll/llcg/036/0700/07600755.gif.

Holt, Michael F. The Political Crisis of the 1850s. Canada: John Wiley & Sons, 1978.

McPherson, James M. Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Missouri Compromise. Accessed 4 October 2007. Available from http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part3/3h511.html.

Oates, Stephen B. To Purge This Land with Blood. United States of America: Harper & Row, 1970.

The Compromise of 1850 and the Fugitive Slave Act. Accessed 4 October 2007. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4p2951.html.

The Missouri Compromise. Accessed 22 October 2007. http://www.sonofthesouth.net/slavery/missouri-compromise.htm.

Waugh, John C. On the Brink of Civil War: The Compromise of 1850 and How it Changed the Course of American History. United States of America: Scholarly Resources, 2003.

Well written Todd–good overview of what has been called by some the most important political event in U.S. History (because of its political impact and how that contributed to the coming of the Civil War).

Thanks Dr. Coles, this is more than a compliment coming from someone as eminent in the field such as you. For any of you who read his message, Dr. Coles was one of my professors at Longwood, my favorite of all my professors. Yeah it definitely was the most important event. I especially love the role that Henry Clay played in much of it, all the effort he put into trying to keep the country together. I’m sure though in the back of his mind he knew eventually it would come to blows. I’m going to do an article in the future on a document I have tied to Gettysburg, I’m going to reach out to you for your thoughts and comments so I can include in the article, so be ready for me Dr. Coles!!!

Enjoyed rea.ding this!

Enjoyed reading this!