Chelsea Plantation (King William County, Virginia)

Chelsea Plantation in 2009.

Chelsea is one of the best preserved and, for the most part, unchanged colonial era homes in Virginia. In about 1705, Colonel Augustine Moore purchased land in King William County, Virginia from the Graves Family. He named his plantation and home Chelsea, after the home of his supposed ancestor, Sir Thomas More. Chelsea is located on the Mattaponi River, approximately six miles from West Point, a town in King William County. Chelsea still stands today, much as it did in the colonial era. Today the house consists of the main front portion which was built in Georgian style architecture and the back wing addition to the house which was built about twenty years after the main block of the house.

It is believed that Augustine Moore began building a one and a half story weatherboard house with a brick foundation in about 1709. The weatherboard house was probably located where the present addition to the main house now sits. Augustine probably began construction on the current main house at Chelsea between 1735 and 1740. This front portion was built in Georgian style architecture. This style of architecture was common from the early 1700s to about 1830 and was especially popular in the South.

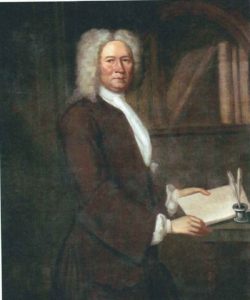

Augustine Moore, painting by Charles Bridges, courtesy of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

The main house of Chelsea exhibits many characteristics of Georgian style architecture. The house is single pile which means it is one room deep. A constant feature of Georgian architecture, which Chelsea exhibits, is that the house is symmetrical meaning that the front and back of the house are the same and the house is balanced upon a central hall. The house has lost its symmetry due to the addition added on. A benefit to a symmetrical house is that it allows for even airflow throughout the house. The house is laid out in Flemish bond with glazed headers. Flemish bond is alternating rows of stretchers and headers. Stretchers are bricks with the long side exposed and headers are bricks with the short end exposed. Glazed headers are created by firing sand with the brick in a kiln which creates a glassy surface. Flemish bond is considered to be one of the most expensive brick patterns and in Chelsea’s case is more expensive since glazed headers were used in the construction of the house. A water table surrounds the first level of the house and a three-course rubbed-brick belt course surrounds the second level. The four corners of the house are made of medium rubbed brick.

The basement of the main house is a full, raised English basement. The windows are double hung sash windows. The roof of the main house is a hipped roof. Around the eaves of the roof are dentils, tooth shaped designs used mainly for decoration. The current chimneys of the main house are not original as they were rebuilt, probably in the 1800s. The front door is a paneled door with a double row transom light over the doorway.

Side view of Chelsea, photograph courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The interior of the first level contains some of the finest wood paneling of any historic home in Virginia. The entire first level is trimmed from floor to ceiling in wood paneling the center hall is done in walnut and the rest of the first level rooms in heart pine. Chelsea is one of few colonial Virginia homes with complete wood paneling on an entire floor. Chelsea’s paneling has been compared to Wilton in Henrico County, which has wood paneling throughout the entire house. On the right of the main entrance is the parlor. The door frame entering the parlor is flanked by pilasters which were hand carved and employ stop fluting in the construction of the pilasters. Some of the features of the parlor room include heart pine paneling, pilasters with stop fluting that flank the window frames and fireplace, and arched window recesses. Opposite the parlor is the study, or library, which at one point was probably used as a bedroom before being converted into a study. The study is not as intricate in detail as the parlor but is still fully paneled as the rest of the first level. The study does not have the pilasters and arched recesses like the parlor but has two doors which open up into two closets. The second floor has two bedrooms which are wallpapered.

Colonel Augustine Moore died in July 1743 and Chelsea passed to his wife, Elizabeth Todd Moore, and upon her death passed to her son, Colonel Bernard Moore. The main house was not sufficient enough for Bernard and his large family, so he built the addition to Chelsea between 1755 and 1760.

Side view of Chelsea showing the addition added by Bernard Moore, photograph courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The addition was built slightly off center of the main house and perpendicular to it. The addition is connected to the main house by a breezeway. The connecting room of the addition is presently the dining room and has two exterior entrances opposite one another. Also on the first level of the addition is a narrow kitchen and two additional rooms. On the second level are three bedrooms all with their own fireplace. The addition, just as the main house, has a full, raised English basement. The addition, like the main house, is laid out in Flemish bond but with few glazed headers in only a couple of locations. The two exterior entrances have covered porches with built in seats and dentil work around the eaves of the porch roof. The roof of the addition is a gambrel roof with dentil work around the eaves of the roof and dormer windows. All the windows of the addition are double hung sash windows.

Other dependencies and structures on the property include a kitchen, smoke house, and packing house which date to the early 1800s and are wooden structures. The exterior kitchen is two levels and has a huge cooking fireplace. The smoke house served the purpose of storage and hanging of meats for curing. At some point in the 1800s there was a laundry house on the premises which was dismantled in the early 1900s when a wall was built on the property. Located about 300 yards south of the plantation manor, in a grove of trees, are the remains of the icehouse. Other structures on the property include farm buildings that date from the early 1900s.

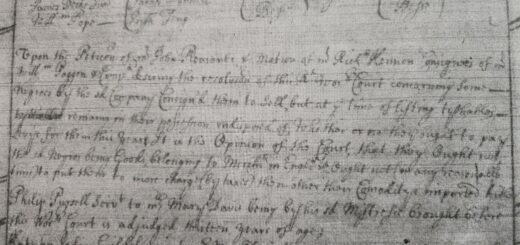

Through archaeological excavations, other structures have been discovered at Chelsea. In 2009, I took part in one of these digs in searching for the root cellar on the property. The remains of the root cellar were discovered about 100 yards southwest of the main house. A root cellar was used to store wines and a variety of vegetables. This site has turned up a number of artifacts including colonial era nails, buttons, shards of dishware and pottery, shards of wine bottles, clay tobacco pipes, slave shackles, and Native American artifacts such as projectile points and beads. The possible location of the tobacco warehouse and slave quarters is believed to be about 200 yards west of the home.

Colonel Bernard Moore (c.1718-1775), painting by Charles Bridges.

After the death of Bernard Moore, Chelsea passed on to his wife, Anne Catherine Spotswood Moore, the daughter of Lieutenant Governor Alexander Spotswood. During the colonial era, Chelsea housed one of the largest repositories of portraits in Virginia; among the portraits were those of members of the Moore and Spotswood families. Colonel Augustine Moore employed Charles Bridges, a painter in Virginia, to paint portraits of himself and some members of his family at Chelsea. The paintings by Bridges included Augustine Moore, Mrs. Augustine Moore and child, Dorothea Dandridge (daughter of Gov. Spotswood), and Alexander Spotswood which are all currently owned by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Two other paintings by Bridges, which are now privately owned, are Two Children of the Moore Family (believed to be Lucy Moore and Bernard Moore, children of Colonel Augustine Moore) and Thomas Moore, one of Augustine’s sons. Chelsea used to house all six of these portraits until they were sold off by members and descendants of the Moore family. Many paintings at Chelsea were damaged during the Revolution by British troops conducting raids near and at Chelsea.

In 1781, just weeks prior to the siege of Yorktown, Virginia in October of that year, General Marquis de Lafayette encamped his forces near Chelsea and used Chelsea as his headquarters. In 1802, Anne Catherine Spotswood Moore died and Chelsea passed to her son, Bernard Moore, Jr. After Bernard Moore, Jr. died in 1806, the house then passed to his two sons, Andrew Leiper Moore and Thomas Moore. Andrew Leiper Moore died at Chelsea in 1828 and the house then passed to his daughter, Lucy, who married Benjamin Robinson. This is how the Robinsons came to own Chelsea. Robert E. Lee visited Chelsea on a number of occasions as his grandmother was Anne Butler Moore, daughter of Bernard Moore and Anne Catherine Spotswood. Lee liked to spend time in the parlor where the portraits of his Moore ancestors were and when asked to join guests in another room he is to have said, “I don’t like to leave my ancestors, these old Romans.” The Robinson family sold Chelsea in about 1874 and the house changed hands several times until it was purchased in 1912 by Pleasant L. Reed of Richmond, Virginia.

In 1934, Reed moved 300-year-old English Boxwoods from Mount Prospect in New Kent County to Chelsea and planted them in the gardens where they can still be seen today. In 1959, after two years of negotiations, William W. Richardson, Jr. of New Kent County purchased Chelsea from the Reed family. In 1968, William Richardson, Jr. died and left Chelsea to his wife Ellen Johnson Richardson. In about 1908, a two tiered Victorian style porch was added to the front of Chelsea. Since the porch was architecturally inaccurate for Chelsea, the porch was removed in 1988. In December 2003, William W. Richardson, III purchased Chelsea from his mother and owned and operated the historic home and property until his death on December 11, 2017. In 2012, Richardson placed Chelsea in a land conservancy easement with the Historic Virginia Land Conservancy. Chelsea was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1969.

The Cemetery at Chelsea

The cemetery at Chelsea.

Surrounded by a brick wall, the cemetery at Chelsea contains six known graves. The soil on the property is soft and sandy, so there may be more graves in the cemetery which may have sunken, along with their markers, due to the condition of the soil. The first grave in the cemetery is the grave of Mary Gage, the first wife of Colonel Augustine Moore. The inscription of her entablature reads, “Here lyeth ye body of Mary the wife of Mr. Augustine Moore who departed this Life the __ day of 1713.” Also buried with her is her infant child. Colonel Augustine Moore’s grave is the second one in the cemetery. His grave is next to his first wife’s, but his entablature was stolen. The foundation which his grave marker sat on can still be seen.

In the cemetery is a fractured portion of a tombstone of a man named Ralph Crawforth. The parts of the tombstone that are legible read, “ye body of Ralph Crawforth…very eminent…died…” He being “eminent” as the tombstone reads could mean that Crawforth was either clergy or judiciary. Also located in the cemetery are the graves of both William W. Richardson, Jr. and William W. Richardson, III. The last grave in the cemetery is that of Henry Forrest, a captain of the Greyhound, a ship owned by Isaac Hobhouse and Company. On a voyage to Virginia in 1722, Forrest died onboard the ship and was ordered to be buried at Chelsea upon arrival. His entablature reads, “Here lyeth ye body of Henry Forrest late of ye city of Bristol[?] who departed this life ye __ of June 1722.”

Grave entablature of Henry Forrest in the Chelsea Plantation cemetery.

References

Long, Todd Eberle. Voices of the Past: The Long and Brooks Family History. Fullerton, CA: Creative Continuum, 2013.

Minchinton, Walter E. “The Virginia Letters of Isaac Hobhouse, Merchant of Bristol.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 66, no. 3 (July 1958): 278-301.

Pollard, Henry Robinson. Memoirs and Sketches of the life of Henry Robinson Pollard. Richmond: Lewis Printing Company, 1923.

Very detailed information. Thank you.

Did you and Cecil ever go visit there?

Beautiful plantation home. Great article. Our visits at this home was interesting.

Remember when Billy showed us the crib that is believed to have been that of Martha Dandridge Washington’s?

Great info!

That was my 10th great grandfather’s home, need to visit it one day

Thanks for checking out my website, Corey. I believe that Chelsea is currently open for tours by appointment only. But you should definitely go see the home. I did some volunteering there right after college.

Todd

Is Chelsea open to the public? If so, when?

I believe as of now, it is open, but you have to make an appointment to get a tour.